Jennifer Walshe

Don't Do Permission Isn't – The Music of Jennifer Walshe

‘I’m very interested in sounds that we hear all the time but do not normally pay any attention to. Twigs snapping in a burning fire, paper tearing, breathing. Also instrumental sounds that aren’t considered “beautiful” in standard terms – those a performer might make when they are warming up, or very tired, or not playing in the normal way. I think these sounds have their own beauty in the way that driftwood or pebbles on a beach or graffiti can.’

The music of the everyday; accidental music, the charm of random vibrating bodies. Jennifer Walshe has the kind of ear that catches these sounds as they pass: the inaudible music of a slowly falling feather; the mad singing of a drunk on a deserted street at 4am; the delights of gadgets; voices arguing in a forced whisper so as not to be overheard. So in life, so in art: performers of her music need at times to operate water sprays, blow up balloons, shine torches, play cigarette lighters in rhythm, imitate the sounds of underwater creatures – to be prepared, in short, to step out of their normal selves.

Jennifer Walshe is one of the most radical minds in Irish new music. Recently turned 33, she has created a body of work brimming with delightfully off-the-wall ideas and has taken that work around the world, receiving commissions, prizes (including the prestigious Kranichsteiner Musikpreis at Darmstadt in 2000), a great deal of acclaim and a certain amount of notoriety. She has created works for a passive-aggressive choir, an opera for Barbie dolls culminating in an unbearably prolonged date-rape scene, a string orchestra piece which pretends the instruments are icebergs and frozen rain, a piece for a solo vocalist who has to perform a hundred pop songs in the space of three minutes. Her list of works is astonishing – there is a feeling of incredible fluency both in the quantity of pieces she has made and in the nature of the music they contain.

It’s clear, even on casual acquaintance, that Walshe’s work is much more than music. Her work is flooded with human beings and objects, with teeming life in all its complexity – messy, funny, disturbing, joyous. Even those works that are written for relatively conventional forces invariably have other dimensions, often quite surreal ones: it is as though the workings of the subconscious mind had suddenly become everyday reality.

Take for example minard/Nithsdale (2003). Written for amplified string quartet with two boomboxes, there is also a fifth performer who sits in the audience with a torch. On cue, 2 minutes and 9 seconds into the piece, he/she briefly shines a light a few times on the viola player’s feet; then, midway through the piece, starts gently ‘stroking’ the first violinist’s back with the torchlight, beginning at the neck and moving downwards. This continues for a minute or so until the operator desists, turning his/her attention thereafter to fixing a steady stream of light on the cellist’s feet. As this curious seduction game proceeds, the musicians play. But their music is anything but conventional. Each of the four instruments is ‘prepared’ (à la John Cage) with a piece of stiff card threaded through the strings in front the bridge, that part of the string that would normally be bowed, creating a complex noise sound, the quality of which is hard to control precisely despite the careful specifications in the score. Later, the two violinists and violist make a frantic pattering sound with the pads of their fingers on the cardboard, while the cellist, ‘staggering around’, plays a passionate if amusingly directionless sliding melody. Later still, all four musicians, while playing, engage in a lively chorus of tongue clicks, the resulting sound suggesting that someone has let a large quantity of frogs loose on stage.

It’s a tremendously engaging, delightful and beautiful piece, but is it anything more than sophisticated messing around? Emphatically, yes. Musically speaking, despite Walshe’s abundant and refreshing originality, there are audible musical traditions in the hinterlands of this piece, most of them recent, including Ligeti-like quasi-synchronicity of instrumental parts, an absorption of Cage’s expansion of the sonic palette of music to include any sound under the sun, and the ‘stochastic’ mass textures created by thousands of minute sonic pin-points so beloved of Xenakis.

Groping around for an adequate description, it’s tempting to call this piece and most of her other works ‘music theatre’. This would be less of a problem if we had any idea what this once-common term means anymore. In the winter of 1957, in a talk on experimental music, John Cage asked a convention of music teachers in Chicago the provocative question ‘Where do we go from here?’ His answer: ‘Towards theatre. That art more than music resembles nature. We have eyes as well as ears, and it is our business while we are alive to use them.’ Walshe quotes this enigmatic passage, which Cage reprinted in his famous book Silence, in response to my question as to whether she considers her work to be music theatre. I take this as a no: all music, she seems to imply, is theatre, not just her own. Attending a concert is a visual experience as well as an auditory one, in the same way that sitting by the ocean is a feast for all the senses, not just the eyes. Cage came to define music as ‘sounds heard’, and so too the word ‘theatre’, in this context, sheds its traditional meaning and signifies something like ‘things seen’. ‘The entire continuum of the senses appeals to me and is really important’, she tells me. ‘For me, going to a concert means listening and watching – the idea that we can selectively utterly shut down our senses is ludicrous’. But isn’t the music finally more important? Maybe: but that is not quite her point. She gives a telling example – the same string quartet played by a foursome of scantily clad young females will have a totally different effect than if it were played by the Arditti Quartet, champions of the avant-garde repertoire, or by four Africans, or by four blind musicians. The idea that that sort of information is unimportant doesn’t hold up to scrutiny. ‘It’s just the way I think’, she says. ‘My pieces take the visual into account’.

This sort of thinking infects all her work. The marvellously titled moving in/love song/city front garden with old men, nominated for Holland’s Gaudeamus Prize in 2002, is her equivalent of a song-cycle (on poems by John McAuliffe) and uses the Schubertian combination of tenor and piano, with just a few differences: the tenor also sings through a megaphone and a karaoke mike, plays with a walkman in the last movement, and produces sounds from sandpaper, paper, a lightbulb, a metal box full of glass, and two radios; the pianist is equipped with an e-bow, crystal glass, a newspaper, paper and a minidisc player. The tenor begins the piece far away from the pianist, and over the course of the piece circles towards the piano. In her mesmerising unbreakable line. hinged waist of 2002 the flute, clarinet and oboe sit amongst the audience, contributing their whistling and spluttering (their material is loosely based on recordings she made of the heating system in her apartment in Chicago) to the more event-filled music of strings and piano onstage and the occasional uproar from a percussionist offstage.

Aesthetic closet

This feeling for the extraordinary in music is not unconnected to her family background. She was born in Dublin in 1974: her father worked for IBM, and was moved occasionally (the family lived in Amsterdam for three years and later San Francisco for six months); her mother is a writer and playwright. Her father played in a pop band and loved The Beatles, Bill Evans and Erik Satie; her mother preferred Elvis. Thanks to this non-highbrow environment the young Jenny learned to play Satie and Chopin, not Bach or Beethoven (‘there was a time when I thought that Satie’s performance directions – “from the corner of your hand”, “be alone for a moment” – were totally normal’). While they were in the States, when she was 10, she announced that she wanted to play the trumpet; later she would be the only girl in the brass section of the Irish Youth Orchestra. Thanks to her mother she early on absorbed the special magic of Beckett; she was taken to see Waiting for Godot when she was 15, and in the years ahead saw various pieces of experimental theatre when her contemporaries in the youth orchestra would have been going to hear the NSOI. In this way she encountered a number of ‘small, weird plays’, not just things at the Abbey or the Gate. Her first composition was written when she was 19, a trumpet quartet entitled Quad inspired by the Beckett play of the same name.

In Ireland she studied composition with Kevin Volans; at the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama (where she did her undergraduate study) with John Maxwell Geddes; and at Northwestern University in the States with Michael Pisaro and Amnon Wolman. She obtained her Doctorate at Northwestern in 2002. She went to the States, she says, because ‘nobody knew me – it was good to go there and wipe the slate clean and start afresh’. Among her great musical loves are Lucier, Ashley, Cage, Feldman, Partch, Ives: the American maverick tradition is very important to her work. Northwestern University had once briefly housed Harry Partch and his instruments, and had a Cage archive and a Fluxus archive; she remembers the thrill of looking at original manuscripts by George Brecht and other Fluxus artists. She felt immediately at home. ‘I remember looking at Michael Pisaro’s bio and it said his interests included “alternative tuning systems and silence” – I thought any place that would hire a guy like that would be right for me’. Also crucial to her development were her studies with the Israeli Wolman. ‘One of Amnon’s metaphors for teaching’, she says, ‘was that of the “aesthetic closet” – he regarded one of his jobs as a teacher to find out what aesthetic or stylistic closet a student was in, give them permission to come out and arm them with the technique they needed to write the music they wanted to write’. She spent the years 1997–2002 studying at Northwestern, and stayed on for one more year, teaching.

One of the things she studied with Wolman was musical notation, which they approached from some radical points of view. They discussed ‘everything from graphic design to painting to photography’; a radical rethink of the conventions of notation has been necessary to enable Walshe to notate the fantastic soundscapes of her imagination. She cites Edward Tufte’s book Envisioning Information as an important source of ideas. ‘Good notation is something I think is extremely important’, she says. ‘I always try to work with the five-line staff as a basis because it’s a continuum that a musician has no problem dealing with – you know without thinking about it that the top of the staff is high and the bottom is low. So you can build from there. Everything has to make sense graphically, to be as simple as possible, and ideally to be consistent from piece to piece.’ It’s curious how the notational innovations in her scores seem logical in retrospect – my own favourite is a ‘body clef’ which indicates which part of the body of the instrument the performer should play on. With these notational tools, and her elegant calligraphy, she has been able to notate even the most extraordinary of sonic gestures in her pieces.

At Northwestern another formative experience was the experimental music class with Michael Pisaro. One of the consequences was that it encouraged her to improvise. Every Friday she would meet with a fellow musician, Jonathan Chen, and improvise on piano, guitar, violin, and trumpet, letting ideas develop organically. After a period of ‘noodling around’ they gradually settled on voice and electronics. This realisation unleashed a new dimension in her creativity.

Miniature Oral Tradition

In recent years she has written a lot of works involving herself as vocal performer. Despite never having had a singing lesson (she confesses, with a mixture of pride and embarrassment), she has been using her own voice as an essential component in her compositions for about the past six years – all her recent solo vocal pieces have been written in the first instance for herself to perform. Despite her virtuoso notation skills, these scores may need to be supplemented by listening to her recordings should another singer wish to tackle them – her own performances in fact have created a sort of miniature oral tradition. Nature data (2004), for voice and dictaphones, first performed in the Schmetterlinghaus (tropical butterfly house) in the Hofburg in Vienna, is a hilarious and virtuosic piece in which the vocalist imitates a range of birds and animals, with memorable cadenza-like moments featuring barking tree frogs and a selection of tailless amphibians. An earlier work, Ná déan NÍL CEAD (2001) for voice and string ensemble, explores the strange process of physically inhibiting sounds in some way – as when the vocalist covers her mouth with her hands or grits her teeth while singing. (The title, in colloquial Irish, could also roughly mean ‘don’t do PERMISSION ISN’T’: one might add that her whole compositional endeavor to date seems to consist of defying this particular injunction.)

A different sort of experience is G.L.O.R.I. for solo voice, which she first performed in the Half Moon Theatre in the Cork Opera House in May 2005. This piece is like an index of all the pop songs a person carries around in her head, and listening to it is like zapping between TV channels. It is entirely acoustic, without recorded material of any kind, and consists of a lightning sequence of fragments of songs linked together in unpredictable ways that sometimes have to do with melodic connections, sometimes with textual ones. Barely pausing for breath, we get snatches of Them’s ‘Gloria’, Patti Smith’s ‘Gloria’, ‘Hallelujah’ by the Happy Mondays, ‘Hallelujah’ by Jeff Buckley, ‘Gloria’ by Laura Brannigan, and many many others, all in the space of three minutes. Compositionally this takes the use of collage technique, briefly in vogue in the 1960s (but more in the visual arts and literature than in music) and drags it, kicking and screaming, into the cut’n’paste era.

And what a voice she has – by turns like a banshee, like a wannabe teenage rock star ‘performing’ in her room, or like a seductress, all tongue and lips. It seems that the one thing she doesn’t really do is, well, sing. ‘Exploring my voice is such a feeling of freedom’, she says, ‘without the slavery of locking yourself into this hellish practice room for hours on end doing vocal exercises’. She is not worried that her vocal pyrotechnics will hurt her voice. ‘Some singers have come up to me after one of my performances and said, I can’t believe you can still talk! We talk all day long – the voice is a pretty strong muscle. Growing up in Ireland you tell stories and put on voices, you mimic accents – it’s totally natural’. Walshe revels in the grain of her voice, and considers it anathema to disguise its individuality.

She relishes performing her own work, but there are drawbacks. A lot of travelling is called for (she admits that in the busiest part of last year, January–October 2006, she didn’t sleep in the same bed for more than ten nights in a row). She also finds it frustrating not to be able to see the performance from the hall. And at times the part of her brain that takes care of all the logistics is sometimes too dominant for her liking, suppressing the creative part. For all that, she points out that she doesn’t know a singer who would be prepared to spend so much time working to get the sounds she wants as she is herself. In that sense performing has become a necessity, and there is no going back; one of her current projects is a CD featuring her works for solo voice. And it is a supreme challenge. ‘Beckett said that when he was writing he had to be the actor saying the lines, the audience watching the play, and the playwright controlling it, all at the same time. You shift through these different roles; performing, or improvising, is something I do a lot when composing’.

What’s wrong with boys

The biggest pieces Walshe has done to date are her three operas. As with much of her work, she treats the conventions of opera with healthy irreverence, drawing on what suits her artistic needs and ignoring what doesn’t. These works play with the idea of opera, deconstructing it and messing around with it. They are massively original contributions to the genre and urgently need to be seen in Ireland. The first of them is her most notorious piece, XXX_LIVE_NUDE_GIRLS!!! (2003), commissioned by the Dresdener Tage der zeitgenössischen Musik and Wien Modern, and premiered in Dresden in October 2003. It was, she admits, a huge undertaking; she wrote both the music and the script (‘more like a television script than a conventional opera libretto’), and did the stage design. The story is based on the Greek comedy Lysistrata, in which the eponymous heroine persuades the women of Sparta, Boeotia and Corinth not to engage in sex with their husbands until the Peloponnesian War has ended and peace has been restored. XXX_LIVE_NUDE_GIRLS!!! shares the comic spirit but ends in tears. Three characters, Gloria, Naomi and Camille, all Barbie dolls, debate what’s wrong with boys, why they are so aggressive; and they decide not to sleep with them until the boys become nicer. In Act 2 the boys show up late at night, drunk, and have various reactions to the girls’ decision, none of them exactly positive. A fight breaks out amongst them, later involving the girls, and Gloria gets pushed off a balcony and killed. The opera ends with Camille and her boyfriend discussing the question of physical intimacy, and quarrelling; then he date-rapes her. This final, disturbing scene has something of the effect of cringe comedy. There are various gags as the rape progresses, so audiences tend to laugh; but by the end, Walshe admits, they’re completely horrified, having to watch the sordid scene to its end. She noticed that ‘sometimes in operas a rape is accompanied by luscious music to make it seem erotic – I thought that was disgusting.’ So she wrote the cheesiest, most schmaltzy music she could imagine for that moment.

The opera got great responses, she admits, and more performances are on the cards. ‘It isn’t common to deal with issues to do with sex in new music; many people find it very provocative to go to a contemporary music concert and be confronted with a rape scene. The audience are forced to take a stand. People tend to have very strong reactions’.

Her second opera, set phasers on KILL!, was premiered in Hamburg and Berlin in January 2005 by the Berlin opera company Novoflot, who commissioned it in conjunction with the Hamburg Staatsoper and the Sophiensaele, Berlin. The work was one of three short operas commissioned from different composers to function like episodes of a sci-fi series. Musically, the work is even stranger than the Barbie opera. All the characters sing either in animal sounds, or sing fragments of pop songs about space. Most of the music that the musicians play is background in style, like the sound design for a film.

set phasers on KILL! brought Walshe up against a dilemma familiar to opera composers throughout the ages: a difference of vision with the director. As a consequence she has resolved always to direct her own dramatic projects from this point onwards. Such was the case with her third opera, Motel Abandon, premiered in Berlin in November 2005, only some eleven months after the previous opera. This work was written to be performed in an apartment, with only three performers: Walshe herself, the Irish actor Stephen Swift, and the French Berlin-based cellist Augustin Maurs. The concept was inspired by the Danish avant-garde filmmaking movement Dogme 95, which prohibits expensive and spectacular effects, relying on hand-held cameras, natural action and no post-production ‘cheating’. Motel Abandon has no stage, no orchestra, no special effects; the performers themselves do the lighting. The DAAD in Berlin loaned a huge 8-room apartment for the performances, which was the set. The audience came in and were told that there were a few ‘rules’: not to switch lights on or off, not to open or close doors, and not to talk. In addition to the sounds made by the performers Walshe made tape recordings, which were placed around the apartment, and a DVD which was playing on the television set; she also directed the performance. Each person has their own story – the whole performance was like a ghost house, with each person going about their business. She found the performances ‘very satisfying’, something she needed to do to work out the frustrations after her second opera.

She tells me quite matter-of-factly that hers is a composer lifestyle – she has resolved to move when necessary, to go where the money is. Since leaving the States in 2003 she spent a year in Schloss Solitude in Germany, then two years in Berlin on a DAAD grant. She is presently on a two-year residency as part of In Context 3, South Dublin County Council’s Per Cent for Art programme, and has a grant from the Foundation for Contemporary Arts in New York. Does she still feel Irish? ‘Well, as they say, you can take the man out of the bog, you know, but… there’s definitely a connection, a pull you feel towards Ireland’. Then again, sometimes being Irish has more advantages when you’re abroad – ‘it’s very useful sometimes to be the eccentric Irish person’. She is very pleased to be doing more work at home; she grew up in Rathfarnham, and is back there working now. And she has a great fondness for Irish traditional music, for lilting, for sean-nós. ‘I’m really lucky’, she says – ‘ever since finishing my education I’ve been able to live by composing. I know the hammer’s going to fall sooner or later’.

Preferably later; quite possibly never.

Published on 1 July 2007

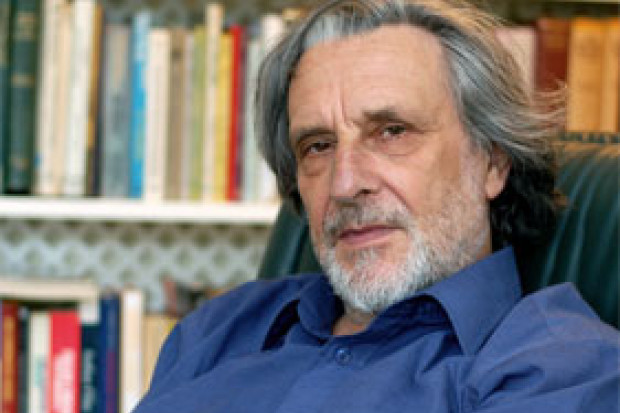

Bob Gilmore (1961–2015) was a musicologist, educator and keyboard player. Born in Carrickfergus, Northern Ireland, he studied at York University, Queen's University Belfast, and at the University of California. His books include Harry Partch: a biography (Yale University Press, 1998) and Ben Johnston: Maximum Clarity and other writings on music (University of Illinois Press, 2006), both of which were recipients of the Deems Taylor Award from ASCAP. He wrote extensively on the American experimental tradition, microtonal music and spectral music, including the work of such figures as James Tenney, Horațiu Rădulescu, Claude Vivier, and Frank Denyer. Bob Gilmore taught at Queens University, Belfast, Dartington College of Arts, Brunel University in London, and was a Research Fellow at the Orpheus Institute in Ghent. He was the founder, director and keyboard player of Trio Scordatura, an Amsterdam-based ensemble dedicated to the performance of microtonal music, and for the year 2014 was the Editor of Tempo, a quarterly journal of new music. His biography of French-Canadian composer Claude Vivier was published by University of Rochester Press in June 2014. Between 2005 and 2012, Bob Gilmore published several articles in The Journal of Music.