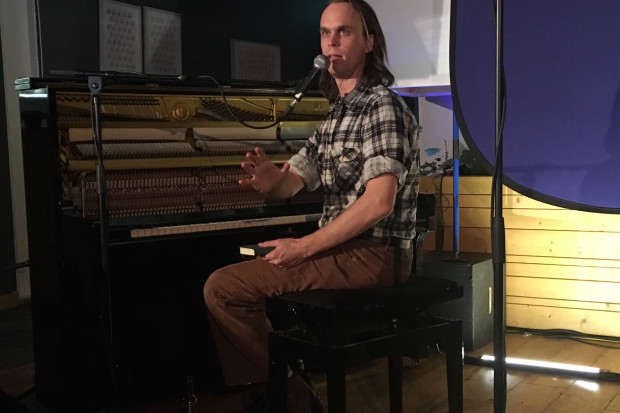

A scene from ‘The Fall’

The Nature of Protest

On 9 April 2015, the statue of Cecil Rhodes that sat on the University of Cape Town (UCT) grounds was taken down, one month after the beginning of the Rhodes Must Fall movement. The Fall, directed/facilitated by Clare Stopford and performed in July at the Galway International Arts Festival, documents this movement in the days leading up to the removal of the statue, and the period thereafter, drawing from the experiences of its cast.

The production begins with the seven-piece ensemble storming the stage – Ameera Conrad, Oarabile Ditsele, Zanadile Madilwa, Tankiso Mamabolo, Siwesandile Mnisi, Sihle Mnqwazana and Cleo Raatus – most of whom were also involved in the writing of the piece, bar Mamabolo and with the addition of Thando Mangcu and Kgomotso Khunoane. They are performing toyi-toyi, a South African dance consisting of the stomping of feet and chanting, often improvised, with close ties to anti-apartheid protest. Because of this association, the dance has been used by South African protestors on many occasions since. The group is made up of graduates from UCT, their voices coming together to weave a rich sound. Their energy is exhilarating, and their momentum is fierce; this is a drive they will tap into several times throughout the piece, a rebellious spirit that permeates it.

Toxic space

We watch as the movement slowly disintegrates after the fall of Rhodes. Without a tangible goal and a unifying motive, the group became a toxic space, only reforming when the Fees Must Fall movement that took place in late 2015 served as a catalyst to pull the members together once again.

The Fall is deeply concerned with difficult, topical questions – its first half focusses largely on the Rhodes Must Fall campaign and the hardships faced by black students at UCT (a university built on land donated by Rhodes – ‘Whose land was it to begin with?’), but after the removal of the eponymous statue, the dialogue moves to touch upon issues of class, gender and sexuality. It questions the nature of protest and whether one should work within the confines of the system despite the fact that it actively works against them and forces them to be dependent on it, or whether they should resort to violence – violence may be a deterrent to dialogue, but dialogue is dictated by the oppressor (‘Why do we have to ask the white man for permission?’ – ‘Because he has the power’). The play never provides answers to the questions it asks, rather it aims to instigate a dialogue.

Evocative

The use of toyi-toyi and music in the piece is powerful – toyi-toyi’s association with anti-apartheid protest lends the weight of tradition to the cause, while the songs the cast sing to the beat of their toyi-toyi are powerfully evocative; many of them focus on pride in nation and people, infused with the desire to decolonise South Africa and move UCT away from its eurocentric sensibilities (‘White people don’t live in a world where white excellence is invisible. But that is our reality’), while others are deeply mournful, lamenting their home’s colonial past and the effects that has on their present. Through music and dance, they ‘found new ways to express [themselves]’. The set, designed by Patrick Curtis is minimal – consisting only of three tables in an open space – but this is used to great effect, serving as improvised percussion instruments and podiums from which the cast make their pleas.

The discourse seems to spread itself a little thin in places, attempting to tackle too many social issues in too short a time, but in the context of the group’s inability to focus on a single issue driving them apart, this is perhaps intentional.

The Fall is a moving account of both the eponymous fall of the Rhodes Must Fall campaign and the fall of the movement itself as it becomes fractured in the wake of its success; an evocative subject matter is emboldened by outstanding performances, perhaps most notably from Sihle Mnqwazana (playing Zukile-Libalele) and Tankiso Mamabolo (playing Qhawekazi) who bookend the production, imbued with a tremendous sense of defiance, and just a hint of hope, as the real process of decolonisation has only just begun.

Published on 2 August 2018

Vincent Hughes is a writer, photographer, and musician based in Galway. He graduated from NUIG’s MA in Writing in 2016, and he participated in The Journal of Music’s Galway City Music Writing Mentoring Scheme in 2017. He has written and photographed for a number of music-based and other news publications, and his pairings of poetry and photography have been featured by Dodging the Rain and An Ait Eile.