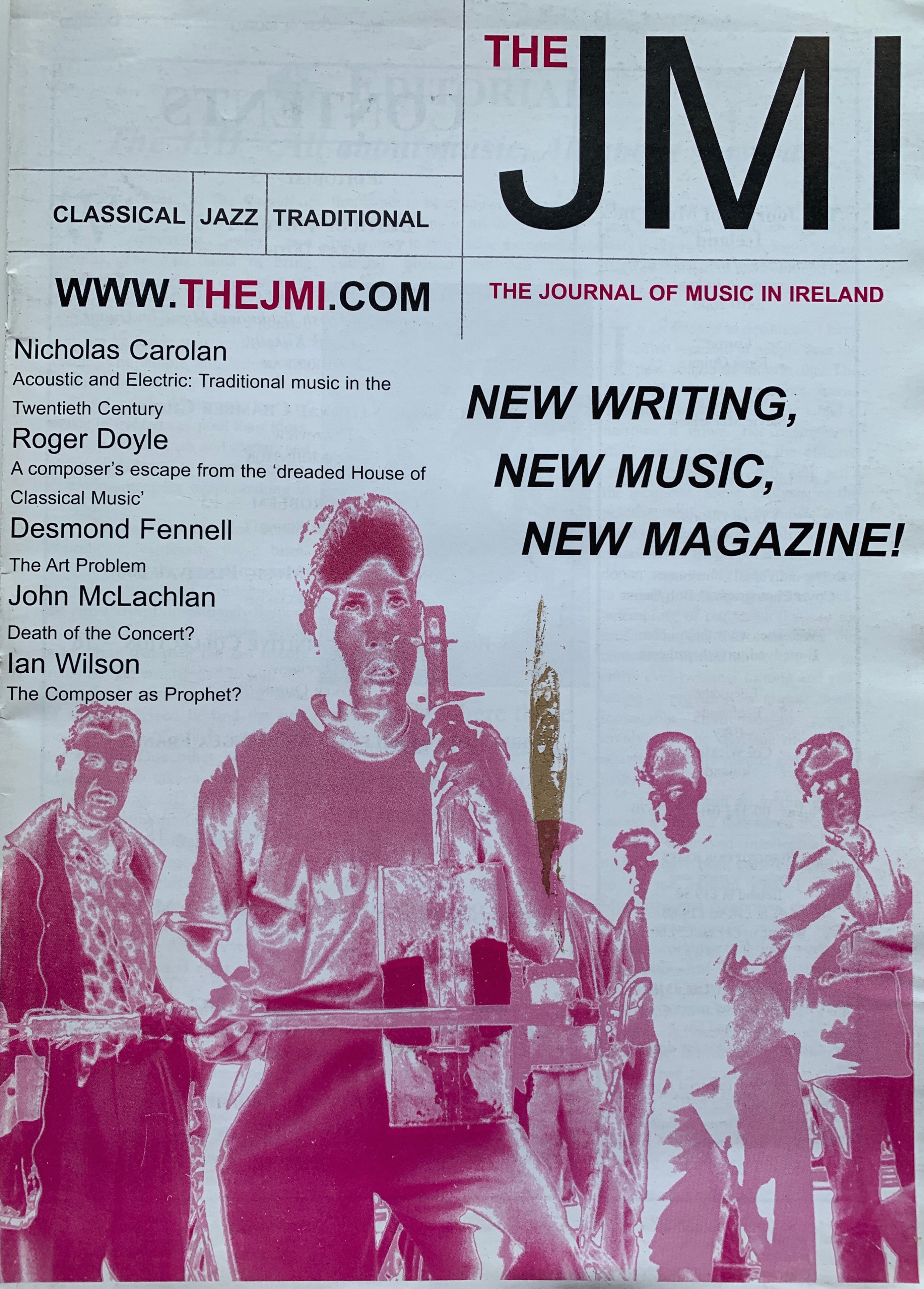

Cover of the first issue of JMI – The Journal of Music in Ireland (November/December 2000)

Editorial: Introducing the JMI

Welcome to The Journal of Music in Ireland. Appearing every two months, JMI aims to bring together new writing on classical, jazz and traditional music in Ireland. Although we have called it a journal, it is not to define it as anything academic. The simple aim behind JMI is to provide a space where those involved at the grassroots level of music in Ireland can pool their ideas, let them meet, clash and clatter, and above all progress to create a healthier environment for music-making in Ireland.

I am conscious that literary periodicals, especially those brimming with ideals, have a reputation for being short-lived. Contemplating the aim above, I immediately think of an e-mail I received from a writer who wrote that over the last twenty years he had contributed to four different Irish-music periodicals, none of which survived beyond the fifth year, and two of which died before the second. One other well-wisher advised us to take a ‘deep breath’ before starting off, his point being that it is not the starting-up of such a journal but the sustaining of it that will be the challenge.

Nevertheless, I suspect that JMI may have advantages over its musical predecessors. Firstly, it benefits from the development of the world-wide-web and e-mail, both of which save us large amounts in postage and telephone bills, and also make many people and organisations quickly and easily contacted. Secondly, the fact that the magazine is concentrating on three styles of music in Ireland – and we intend on including more – rather than on just one, naturally gives us a broader range of appeal. That said, the intention is not to be exhaustive, covering every happening in all three spheres, but simply to emphasise the common cultural ground between these strands, challenge the polarisation that exists, and try and present a more accurate portrayal of the collective challenges facing music and musicians in Ireland. Thirdly, however, and probably what offers the best chance of survival, is that the appeal of classical, jazz and traditional music in Ireland, both at home and abroad, is historically unprecedented, and if a music magazine appearing only every two months cannot sustain itself in this sort of environment, then it was probably never meant to be.

In an attempt at definition, I have often repeated to people over the past couple of months that JMI will primarily be about music. This may sound vague, but I feel it narrows it down. For example, it shall not be reliant on the effusive ‘star interview’, the ‘sell, sell, sell’, the incessant ‘scene’ analysis, or the practice, widespread in music commentary, of intellectualising the manoeuvres of corporate marketing departments as ‘culture’, as opposed to naming it as what it is – the quick-assembling of our cultural space for profit. The din that constitutes our communal mental environment – an entity ever-twisting, turning and vanishing – provides an almost insurmountable challenge to people involved at the coalface of musical activity who, by nature, must try to make sense of it.

In the run up to this issue I issued a circular that stated the need for an ‘improved intellectual climate’. I have been pulled up on this, so let me explain what I meant. Musicians and composers should be able to create music, vaguely secure in the knowledge that their work will enter into some sort of rational and discerning climate of thought, where their music, be it celebrated or dismissed, is treated constructively. Otherwise, if their music is not treated as that important thing called ‘music’, such as the world professes to define it, their actions lose meaning and value – in fact, most of them probably wouldn’t bother in the first place.

Despite much talk about the importance, and even sacredness, of music, it is not treated, in words and action, with such reverence. I would guess that most musicians and composers wouldn’t mind so much if they an were told they were expendable and subsequently dismissed – they would at least have a clear battle on their hands – but when they are told feverishly about their importance to the world, and yet not received as such, it paralyses and frustrates them. Many in the world believe that music has won its ‘recognition’ battle, with only minor tweaking still to be carried out. Those involved in the creation of music, however, see only music’s unlocked potential; they do not see a booming record industry as their raison d’etre, the culmination of their campaigning, practice, talent, thought and action. For those in music looking out, it is only a beginning.

Musicians and composers have yet to collectively try and challenge the prevailing slippery ideologies, maybe only because the prospect of it is so inhibiting, maybe because they believe they can ‘transcend’ such intellectual trivialities. Most of the speaking-up for discernment and integrity in the face of ruthless market forces is done by a consistently small number, with most of the rest of us undermining what little work they try to do. We need to break the collective silence. The policy of ‘play, compose, and let the music take care of itself’ does not serve us well.

Whatever about these, perhaps lofty ambitions, the fact remains that the relationship between the composition and performance of music on one side, and creative thought and writing on music on the other, is often one of antagonism. In classical music, critics often leave composers and performers incensed, particularly in the case of new music. As a student of the Waterford IT music degree, the extraordinary capacity of music of the early 1900s to illustrate the suppressed discord in society that was to erupt into two World Wars was often brought to our attention by lecturers. It is an anecdote from the arts that society holds significant. Contemporary music’s tough stance with society continues, however, not because composers are trying to predict more World Wars, but because society requires some sort of moral impetus, whether it comes from music or not. Yet Contemporary music is not praised for highlighting this friction and refusing to pamper us with advanced twenty-first century muzack. Instead, society, sweet-talked by ‘scene’ analysis, accuses it of getting carried away with angst, believing it is a fad and that none of it will be remembered.

In the case of traditional music, so much writing over the years has been so unrepresentational of the actual musicians’ experience, and caused so much consternation, that writing and analysis is now often regarded as simply the meddling of ‘academics’. Furthermore, in an absurd national campaign to remedy this, and align New Ireland with ‘the tradition’ and all the street-cred that it brings, many publicly writing on traditional music are adhering to an ecstatic and comic style, treating the subject matter not as ‘music’, or anything of the sort, but as the mystical product of this vague entity called ‘the tradition’ – as if no other music had such a thing!

The effect is a collective numbness on the part of traditional musicians to the media world around them. Despite the cultural hinterland that bore traditional music being in decline, the music is cajoled into playing out its existence as if nothing’s changed, still being talked about using tired old language, still being thought about it within stale mental perimeters, and, already under strain from our tough new commercial world, the music is prodded into battle without an intellectual leg to stand on.

‘Ecstatics’ babble about the glory and strength of ‘the tradition’, and yet fill our cultural space with anxiety about how ‘the tradition must keep changing if it is to survive’. This incessant paranoia is the grating and destructive element in traditional music. The constant brow-beating over ‘tradition’ breeds reactionary music, musical statements of what musicians aren’t or don’t believe, rather than what they are and do believe.

Which brings me to Irish jazz, a genre not without its problems but yet does not seem to be condemned to eternally chasing its Irish-cultural-baggage tail. The last ten years have seen the Irish jazz scene grow stronger and music abounds that is fresh and Irish. Is it because it doesn’t have to do bloody battle with Irish cultural baggage simply to get on?

I may have done too much prophesising, but it is difficult not to be excited, imagining what is possible when such ventures as JMI take off. JMI will aim, at least, to start levelling the playing field for constructive thought on music, against that thinking which paralyses us. To that end, I hope many will become involved, and help us realise JMI’s potential.

First published in JMI: The Journal of Music in Ireland, Vol. 1 No. 1 (Nov–Dec 2000), pp.3–4.

Published on 1 November 2000

Toner Quinn is Editor of the Journal of Music. His new book, What Ireland Can Teach the World About Music, is available here. Toner will be giving a lecture exploring some of the ideas in the book on Saturday 11 May 2024 at 3pm at Farmleigh House in Dublin. For booking, visit https://bit.ly/3x2yCL8.