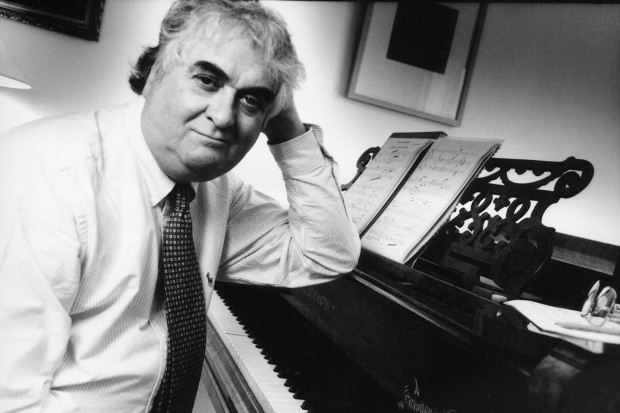

Arnold Bax, E.J. Moeran and Tilly Fleischmann in Kinsale, County Cork, in 1937 (Photo: Fleischmann Collection, University College Cork)

Arnold Bax, the Fleischmanns and Cork

On Monday October 5, 1953 Aloys Fleischmann wrote to Sir John Barbirolli:

Dear Sir John,

I feel I must write to tell you of the tragic circumstances under which our dear friend Sir Arnold met his death. He had arrived here last Thursday, having spent a most enjoyable week in Dublin previously with the Larchets. Only last Tuesday I conducted a programme of his works in the Phoenix Hall with the Radio Éireann Symphony Orchestra (Overture to Adventure, Left Hand Concertante with Harriet Cohen and The Garden of Fand) with which he was greatly pleased. On Friday he examined here at the College, and on Saturday spent the afternoon with John J. Horgan – whom you remember – at the Old Head of Kinsale, when he saw a most striking sunset over the Atlantic. Strange that the last work of his own which he heard should have been The Garden of Fand, and that he should have been looking out over the sea, her garden, within a few hours of his death! Though quite himself all day, on arriving back at the Horgan’s house he suddenly felt ill and asked to be taken home. As soon as my wife saw him she realised that a very serious heart attack was imminent, and sent for Prof. James O’Donovan, our chief physician here. He tried injections and did everything he could, but within an hour Sir Arnold had passed away, quite peacefully and without any pain.[1]

In describing here Bax’s final days, Fleischmann not only records the end of a long relationship with Ireland which had begun for the composer fifty years before, but also the end of a close association with Cork, and in particular the end of a warm friendship of some twenty-five years standing with the Fleischmann family.

In a previous article in these pages,[2] I outlined Bax’s early enthusiasm for Ireland and for things Irish. From 1902 until the outbreak of the Great War he was a frequent visitor here, and indeed from his marriage in 1911 until he eventually returned to England in 1914, he was resident in Dublin. His imaginative and emotional response to the country was undoubtedly important in the shaping of his compositional style. But his relationship with Ireland was more complex than this, and he came to feel that by some spiritual affinity he was partly an Irishman. This feeling found its principal expression in literary activity, and in particular in the emergence of a literary alter ego, Dermot O’Byrne, under which name he published stories, plays and poetry. At this period he was hardly known at all as a musician in Dublin, certainly not publicly, and his life in Ireland was unconnected with the promotion or performance of his music. There is little doubt that Bax saw Ireland as his ‘Land of Heart’s Desire’, a place apart, removed from the hum-drum realities of day-to-day concerns, and on crossing the Irish Sea, as he said, he shed his identity as an English composer and became instead Dermot O’Byrne, author and Irishman – a make-believe role he created in order to play a part in what was also, I suggest, for him largely a make-believe Ireland.

Tilly Fleischmann

If it is unlikely that much, or indeed any of his music had been heard in the city, Bax’s name at least was not entirely unknown in Cork before the end of the Great War, even if what was known about him was rather garbled. News of the writer-composer had percolated down from Dublin, and Tilly Fleischmann tells how in 1917 she first heard of him from a certain J. J. O’Connor who came to see her, she says, in a state of great excitement.

His first words were ‘You often said to me that the Irish people expect a Chopin or a Grieg to fall from the skies, that it took years and successive precursors to appear, before the ground was really ripe for a genius. Well. This time you are mistaken. A star has fallen from heaven – an Irish genius – Dermot O’Byrne.’ He told me, in an awe struck voice that Dermot O’Byrne, a ‘spoiled priest’ from Maynooth, was writing music under the pseudonym of Arnold Bax, that he had written seditious poetry after the Rising in 1916 and ‘that of course the works of a rebel would never be performed in England.’[3]

Tilly Fleischmann’s curiosity was naturally piqued by this intriguing intelligence. She set about ordering some of the piano music and songs from London, and was sufficiently impressed by what she received to follow the composer’s career with interest and enthusiasm from then on.

The Fleischmanns were very much at the centre of musical life in Cork at this period. Tilly’s father, Hans Konrad Swertz, had come to Cork towards the end of the previous century and had held the prominent position of organist and choirmaster at the Cathedral of St Mary and St Anne. Tilly herself had trained as a pianist in Munich from 1901 – studying under Bernard Stavenhagen, the last pianist to study with Liszt – and she had given numerous recitals there before returning to Cork in 1906. Although advised that a solo piano recital would not attract a Cork audience, she was undaunted by this and the year she returned she gave one of the few such recitals to be held there up to that time. She continued to give recitals with programmes of a wide range and variety and she acquired a formidable reputation as much, it might be said, for her determined personality as for her abilities as a pianist. She also quickly established herself as the most sought after piano teacher in Cork.

While studying in Munich Tilly met and married Aloys Fleischmann, a young organist and composition pupil of Rheinberger’s who had begun to make a name for himself as a composer in his native Bavaria. He came with her to Cork in 1906, succeeding Hans Konrad Swertz who had resigned his post in the Cathedral. Swertz’s departure was occasioned by the Moto Proprio of Pius X, issued in 1903, which sought to regulate the use of music in the Church. This effectively spelled the end of the repertoire he, his choir and the Cathedral congregations had been accustomed to, and Swertz was clearly not prepared to adapt his taste to Papal legislation. But Fleischmann was enthusiastic and proceeded to implement the directives, although he met considerable opposition in doing so. The substitution of boys’ for ladies’ voices was unpopular, as was the abandonment of the colourful masses of Mozart, Haydn and Gounod for plainchant and the austere polyphony of the sixteenth century.

After Munich, Cork must have seemed musically and culturally fairly barren in the early years of the twentieth century, and neither Tilly nor her husband can have been altogether surprised to find themselves facing an uphill struggle in their respective spheres. But, having decided to settle in the city, they were both quite prepared to confront provincial indifference and to do battle with philistinism and ignorance when necessary. They lived out the axiom that if you insist on high standards you will eventually see improvement, and they found that they had many supporters in Cork who appreciated their dedication, and many allies in their artistic endeavours.

Dermot O’Byrne disappears

It would probably have surprised Tilly Fleischmann had she known that Dermot O’Byrne was to disappear altogether from the Irish literary scene so shortly after she first heard of him. Although Wrack and Other Stories was published by the Talbot Press in Dublin in 1918, it is not clear if Bax came over for the event, and his first visit to Ireland after the war, it seems, was not until the following year – possibly for the publication, also by the Talbot Press, of Red Owen: A Play in 3 Acts. These two literary works were Dermot O’Byrne’s final appearance in print,[4] and their publication marked the end of an era for Bax. The Ireland he knew was fast disappearing, and he did not visit the country at all during the Anglo-Irish War or during the Civil War. He realised that the golden age of his Irish dream was over and, putting off the role of Dermot O’Byrne, he allowed Ireland to slip into the background of his interests.

Without doubt this was partly due to a growing reputation in England which demanded more and more of his attention. The 1920s were the years of Bax’s greatest critical acclaim, and he was widely recognised as one of the foremost composers of his day. At the outset of the Great War he wrote to a friend that he had ‘been swaying backwards and forwards between two courses – that of entering the army (and becoming bold and British thereby, or pretending to be) and that of plunging into a narcotic ocean of creative work.’[5] Bax chose the latter course, and composed steadily throughout the war years, producing some of his very best music. The result of this was that by the end of the war there was a considerable number of important scores ready for performance, while there was little or nothing by his contemporaries – all competitors for the public ear – who, as Lewis Foreman puts it, ‘had, by and large, been involved in more serious matters’ between 1914 and 1918.[6] The time was ripe to establish himself as a major figure, which he succeeded in doing, and his extraordinary productivity during the early 1920s enabled him to consolidate this position.

Ireland had not altogether ceased to engage his imagination, however. There were a number of works with an Irish connection written during this period – the Five Irish Songs of 1921 (settings of Colum, Synge and Joseph Campbell); the Three Irish Songs (settings of Colum) and the Oboe Quintet of 1922; and a setting of St. Patrick’s Breastplate dating from 1923, together with a few other lesser works – although he wrote very little else in this Irish vein after these appeared. But a distinct second phase of renewed personal contact, and a resumption of regular visits to the country was initiated in 1928 by what must have been a completely unexpected invitation from Cork.

A preposterous proposal

The Father Mathew Feis, a competitive festival, was founded by the Capuchin Fathers in Cork in 1927 along the lines of both the long established and very successful Dublin Feis Ceoil which had first been held in 1897, and an earlier Father Mathew Feis which had been established in Dublin, also by the Capuchin Fathers, in 1908. Various adjudicators were engaged to judge the music competitions at the first two Feiseanna, including Annie Patterson, one of the founders of the Dublin Feis Ceoil, Carl Hardebeck, Arthur Duff, and Robert O’Dwyer. But when the committee met to discuss the engagement of an adjudicator for 1929 Father Michael O.F.M. Cap., the prime mover behind the Feis and president of the committee, emphatically wanted a musician of international standing and suggested that an invitation might be sent to someone like Sir Edward Elgar, or perhaps Sir Henry Wood.[7]

As one of the city’s most prominent musicians Tilly Fleischmann was a member of the Feis committee, and she was appalled at this idea. She fully realised how underdeveloped music was in Cork and thought that such an invitation would most likely result in embarrassment. She countered his perfectly serious suggestions with a bantering suggestion of her own.

‘It is a wonder’ Father Michael I said ‘that you don’t write to Sir Arnold Bax.’ ‘Who’s he?’ said Fr. Michael. I told him. ‘And where does he live?’ I said I didn’t know but I thought it was in London. Well we had a good laugh, I’m afraid rather at Fr. Michael’s expense – but in which he joined merrily. The meeting was adjourned for a fortnight.[8]

But what Tilly Fleischmann intended to be a deliberately preposterous proposal had unexpected results, as she discovered about a week later when she met Father Michael ‘sauntering down the South Mall.’

‘He’s coming,’ said he in great glee. ‘Who?’ said I. ‘Arnold Bax, of course. I just wrote “Arnold Bax, London” and he got my letter!’ ‘Well Father’, I said, ‘I never thought you would have the courage to write to him or that he would have the humility to come.’ ‘Oh,’ said Fr. Michael cheerfully, ‘he is delighted to come. Read his letter.’ I read it there and then. It was certainly a charming warm-hearted letter saying how much pleasure he would have in coming and that from now on he would be looking forward to his visit to Cork.[9]

Not only did Bax’s presence lend lustre to these early Feiseanna, but he was in many ways an inspired choice of adjudicator. His ready acceptance of the invitation was undoubtedly prompted by his early love for Ireland, and his generous support for the Feis, as well as his genuine pleasure at being invited to Cork is surely reflected in his refusal to take any remuneration for three consecutive years of adjudication work. Tilly Fleischmann’s fears of embarrassment proved groundless, and of all the distinguished English musicians who might have been invited it is difficult to think of one who would have had a greater personal interest in the proceedings.

The Fleischmanns looked after him when he first arrived in Cork. ‘I want to send you a line to tell you how very touched I feel by the great kindness you and your husband have shown me this week,’ he wrote to Tilly from Dublin when the 1929 Feis was over. ‘The king of Munster could not have been treated more regally.’[10] For the Fleischmanns part, his acquaintance will certainly have enhanced their status in the cultural life of Cork. But whatever element of lion hunting there may have been in this association initially – and, human nature being what it is, there may well have been a little! – it was quickly replaced by a genuine and rapidly deepening friendship. Bax and the Fleischmanns clearly found sufficient pleasure in each other’s company for invitations to be extended and accepted for the next twenty-five years or so, and with the exception of the years of the Second World War as we shall see, they welcomed him to Cork each summer.

An Irish fairy tale

Through the Feis initially, and later through the Fleischmanns, Bax also made many other friends in Cork – Daniel Corkery; Charles Lynch, the pianist, of whose abilities he had such a high opinion and to whom he dedicated the Fourth Sonata for Piano; Maura O’Connor the singer; Seán and Geraldine Neeson of whom he was particularly fond; Seamus Murphy the sculptor who was eventually to make his death mask and carve his tombstone, and his wife Mairead; J. J. Horgan, the City Coroner, one of the staunchest supporters of various Fleischmann enterprises, and his wife Mary. But the Fleischmanns remained the focal point of his Cork acquaintance.

Whatever standards of execution Bax may privately have expected to find as an adjudicator in Cork, it seems that he was in for one or two surprises. The greatest of these was hearing the Cathedral Choir, which Aloys Fleischmann entered for one of the choral competitions in 1929. So great was the impression that this performance made on him that he took the unusual step of publishing his opinion on the quality of the singing. ‘These performances were a revelation to me,’ he duly wrote to The Daily Telegraph.

The choir sang for about an hour – plainchant rendered with an intense devotional feeling and works by Orlando di Lasso and other composers of the difficult and complicated sixteenth century polyphony. I had no idea that Ireland, up to the present time could show anything indicative of such a high degree of musical culture. I was told that the singers were very tired after their arduous work during Holy Week and that at ordinary times they could do even better; but what I heard convinced me that this choir could hold its own in competition with any organisation devoted to the rendering of similar music in any part of these islands. The very greatest honour is due to Herr Aloysius Fleischmann, the organist of the Cathedral and trainer of the choir. This gentleman is a very fine all-round musician, and would be an inspiring influence in any musical circle in which he might be placed.[11]

It is not difficult to imagine what an endorsement like this must have meant to Fleischmann. Although over the years his efforts and achievements had come to be appreciated locally, the exact measure of his success in cultivating ‘unploughed land, hard to plough’, as he put it, had at last been fully and publicly acknowledged by an objective and unimpeachable authority. ‘We all felt very lonely after you had gone. Your visit was like a part of an Irish fairy tale,’ he wrote afterwards to Bax.

Your kind words have given the Cathedral choir tremendous courage and several members including myself have received letters of congratulation from England, America, Italy and Germany. This ‘dull, lifeless music’ is recognised at last after 20 years of struggle and I don’t know how to thank you for it.[12]

A developing friendship

Later in 1929 Tilly organised a recital devoted entirely to the works of Bax. This took place on November 20, and was advertised in The Cork Examiner as an ‘Arnold Bax Evening’, the performers being Doreen Thornton, soprano; Seán Neeson, baritone; Geraldine Sullivan[13] and Tilly Fleischmann, piano. The programme consisted of a selection of songs; music for two pianos – Moy Mell: an Irish Tone Poem, and Hardanger, which had only just been published; and various pieces for piano solo including What the Minstrel Told Us. There was an introductory talk by Daniel Corkery on the composer and his long association with Ireland.

These must surely have been amongst the earliest performances of any of Bax’s music in Ireland, and almost certainly the first performances in Cork, and they were heard by a large audience. There was a long, appreciative notice in The Cork Examiner referring to the composer’s recent appearance as an adjudicator at The Father Mathew Feis, and how ‘the organisers of the recital were interpreting a general desire in enabling Cork music-lovers to hear a well-arranged selection of his most typical works’. ‘His compositions,’ the review continued, ‘are not very well-known in provincial cities, their difficult construction calling for a high standard of execution that is naturally rare. Few singers and musicians feel competent to interpret his subtle methods, but the attention and enthusiasm of the audience at the recital showed that the public welcomes and understands him.’[14]

Tilly wrote to him about the event, forwarding the press notices. ‘My dear Frau Fleischmann,’ he replied,

Thank you so much for telling me about the concert and for the cuttings. I am so very glad you were pleased with the evening and considered it a success: I wish I could have been there and shall look forward to hearing you play when I come to Cork at Easter. Thank you indeed for asking me to stay with you. Of course I accept with the greatest delight.

When you next see Dan Corkery will you thank him most warmly from me for talking so very sympathetically about me and my work. I think it was very good of him.[15]

At Christmas the Fleischmanns sent him as a present a book by Corkery, probablyThe Stormy Hills which had just appeared, and they did not forget his sweet tooth. In a letter dated ‘Xmas Day 1929’ he thanked them both for remembering him so generously.

I shall be immensely interested in Dan Corkery’s book and how well you remember my penchant for sweets! – all the nicer because made at home.

I want to send you (as some little return for your goodness) the score of my Second Symphony, but I am not quite sure if I have the number right (I am awfully bad at addresses!) Will you very kindly send me a card, and I will post the Symphony to you at once. It has just been produced by Kussevitsky in Boston for the first time anywhere, and judging from the cables I have received from him, it has had a great success. He is doing it again in Boston on Jan 3rd and 4th and in New York in the ninth.

Dear Aloys, will you tell the Choir how much I appreciated their Christmas greeting.[16]

Thus the pattern of their friendship was established from the very beginning. For a few weeks each year Bax became a member of the family, joining the Fleischmanns on their annual summer holiday in Oysterhaven, in Glengarriff or in Kenmare. They usually tried to make his trips as memorable for him as possible. They took him to see many different places around Munster, and brought him to visit many of their friends – ’but don’t imagine that I desire any more charming company than that of the Fleischmann family,’[17] he would say when Tilly suggested that he was sure to find them dull.

Most of his letters are addressed to Tilly, and again and again they emphasise how difficult he found it to return to England. And she had the thoughtful habit of sending a parcel of wild heather after him to remind him when he arrived home of the countryside he loved so well. ‘Thank you so much for sending the heather which arrived in good form,’ he wrote from Worcester in 1935. ‘It was sweet of you to think of it. There is rather a tumultuous and hectic atmosphere down here – and I sigh for the peace of Oysterhaven. I think my work will go fairly well, but that is all.’[18] The Fleischmanns also kept him supplied, usually in the form of Christmas presents, with any interesting books by people he knew here – such as Maude Gonne’s Servant of the Queen, which they sent him when it appeared, Corkery’s Earth Out Of Earth, and Seamus Murphy’s Stone Mad. Bax reciprocated with his latest published scores:

I am sending you as a Christmas card [he wrote in 1932] the miniature score of my 4th Symphony which had three performances in one week about a fortnight ago. This is the first small score of any of my things published, and I feel very grand, almost like a classic![19]

Bax was essentially a retiring man who preferred to avoid the limelight if at all possible. One thing that struck his Cork friends was his almost painfully shyness, and in spite of his recognised stature as a composer, his extraordinary modesty. To Geraldine Neeson he was an elusive personality. He seemed ‘the typical, upper middle-class Englishman, reserved, well-mannered, top lip tight across his teeth, his eyes wary.’ Oddly enough, given how often in his letters to Tilly Fleischmann he expresses his particular fondness for the Neesons, it took her quite a while to feel comfortable in his company, although her husband, she says, was quicker in establishing a rapport with him.[20]

Once he overcame his shyness it seems he was a most entertaining companion. Daniel Corkery remembered how the Fleischmanns brought Bax to see him each year when he was living in Ovens, County Cork, and how he came to look forward to such visits because there was sure to be good talk and much laughter. On every visit he would climb a hill above Corkery’s house and name all the mountain peaks of Munster that range themselves around from the extreme east to the extreme southwest. Corkery recalled, too, his love for the rich lore of Gaelic place names, and that he ‘would wonder how such names as Sugarloaf or Bray could be suffered to remain.’[21] Tilly Fleischmann confirms this interest of his in the derivation of place names: ‘If we were visiting some place he had not seen before he would ask Aloys Óg for its name and translation,’ and in remarking that ‘these lovely poetical Irish place names were still a living story of romantic Ireland, alas now dead and gone,’ she probably put her finger on the source of its appeal for him.[22]

Aloys Óg

Bax followed the burgeoning career of young Aloys Fleischmann with interest. ‘He is a brilliant boy,’ he wrote to Tilly in 1931, ‘and so charming and modest at the same time. You and Aloys must be very proud of him.’[23] When Aloys Óg – as he was referred to in the family to distinguish him from his father – returned from his studies in Munich in 1934 to take the up the position of Professor of Music in University College Cork he found Bax more than willing to lend his name and support to his various activities, and he became a patron of the Music Teachers Association which was founded by Fleischmann in 1935, and a patron of the Cork Orchestral Society in 1938. There was one thing he consistently refused to do, however. Amongst the first things Fleischmann undertook after his appointment to the Chair of Music was to establish the University Orchestra, later the Cork Symphony Orchestra, and he made a point always of featuring a work by an Irish composer in the orchestra’s programmes. Naturally he also wished to do a work by Bax. But Bax’s existing orchestral scores were technically beyond the scope of the orchestra at the time, ‘and though I often pressed him to write something specially for us,’ Fleischmann said, ‘he used to say that he was incapable of writing for any thing less than an established professional orchestra.’[24] He also declined to contribute a literary piece to the journal Ireland To-Day when, in 1937, Tilly approached him on behalf of Edward Sheehy, a friend of Aloys Óg’s, who was the editor. ‘I am afraid that I have no remains from my old literary days that would be any good to Sheehy,’ he answered, adding wistfully ‘and nowadays I never write anything, alas!’[25] The days of Dermot O’Byrne were well and truly over.[26]

In 1937 Bax was named in the Coronation Honours List, and he received the communication from Buckingham Palace while he was on a touring holiday in County Kerry. He was very disconcerted by this offer of a knighthood and his first reaction was to refuse. Eventually however he was persuaded to change his mind, and the friend who was driving him around Kerry stopped the car at the next village and literally stood over him while he worded a telegram of acceptance. ‘A perplexed but excited postmistress coped with the unusual situation,’ as Lewis Foreman tells the story, ‘and the visitors went on their way. Nothing more was said about the episode, but the next morning most of the Irish papers carried headlines announcing the news – a striking tribute to the efficiency of the Post Office grapevine.’[27]

One can understand how Bax might have felt a little diffident with some of his Irish friends about the knighthood, and he seemed at pains to emphasise that it was an honour for English music as much as for him personally. ‘I realised that as it was a purely artistic tribute there would be no sense – and some discourtesy – in refusing,’ he wrote to John J. Horgan. ‘Anyway the London musical world seems pleased about it since no mere composer was knighted since Elgar in 1904.’[28] The irony of Dermot O’Byrne, author of A Dublin Ballad and Other Poems which was suppressed as subversive by the British censor in Ireland, having become Sir Arnold Bax, ostensibly a pillar of the English musical establishment, cannot have escaped him. But he need not have worried: no one appears to have considered his acceptance in any way inappropriate. While appreciating his interest in Ireland and the various manifestations of this interest both in music and literature, it is clear that his friends here never held him to be ‘anything else than a patriotic Englishman,’ as Daniel Corkery put it.[29]

The war years

Bax introduced E.J. Moeran to the Fleischmanns in 1936, and in due course he also became a very close friend, often staying with them in Cork en route to Valencia Island or to his beloved Kenmare – but that is another story! In 1939 he took Balfour Gardiner on a tour of his favourite places in Ireland, and of course he too was brought to visit the Fleischmanns. After their departure, Gardiner wrote to Aloys Fleischmann that Bax was ‘very reluctant to leave Ireland and thought of returning there soon. He may already have done so.’[30] If he did in fact return on this occasion, it was in all likelihood his last visit for six years.

Unlike his reaction in 1914, the threat of war now depressed him considerably, and he stopped composing. ‘My dear Tilly,’ he wrote near the end of December,

It was indeed good of you to send me Corkery’s new book.[31] It was delightful to see your familiar handwriting again and to receive your always kind greetings and those of the two Aloys’. Of course I intended to write to the family before Christmas, but all these fearful events are very distracting at times and I cannot adapt myself very well to the conditions. I have written nothing at all since August, and I doubt if anyone else has either.

I hope to be able to see you all again before the new year is out; but as you know one now needs a permit to go to Eire at all. As I am above military age I do not suppose that there would be much trouble about this, but sea travelling is a dubious delight at present.

I hope you are all well and that life in Cork is normal and quiet.[32]

But, unlike Moeran who journeyed to and from the country throughout the war, Bax came to feel that he ought not to travel to Ireland. In a letter to Aloys Fleischmann in 1940 he makes the surprising statement that ‘for many reasons I would love to come to Eire, but I fear it is morally, if not physically, impossible at present.’ And he refers again to the difficulty he found in composing:

I cannot do any work under war conditions. It was very different during the last war. But then I was young and on fire creatively. Nothing could stop me in those days, and from 1914 to ‘18 I did some of my best things.

I am looking forward to visiting you in your new – and seemingly – charming home. I regard you as one of my best friends, dear Aloys, and am ever grateful for all your lavish kindness and hospitality in the past.[33]

Although he did begin to compose again in 1942, there remains a prevailing sadness about the letters he wrote to the Fleischmanns at this time, which is not altogether to be explained by the war. He was, of course, experiencing other difficulties. He, his brother and his sister suffered severe financial setbacks during the war years as their incomes were derived almost entirely from London house property, and indeed Bax himself, ‘always casual and negligent about the demands of the real world,’ as Lewis foreman puts it,[34] found that he was in trouble with the Inland Revenue.

But the source was really something more fundamental in his character. His inability to reconcile the conflicting demands of life and the dream, and his seemingly ever-present desire simply to escape from unpleasant, or even inconvenient realities, meant he had to live constantly with great emotional tensions. These became more acute as he got older, especially as the bitter reality of ageing itself was something he found very difficult to accept. It is as though his ceaseless attempts to sustain the dream exhausted him as much as his inevitable failure to do so disappointed him, and certainly by the end of the 1930s one gets the impression that he was a tired and saddened man. While anguished conflict and a longing for an unattainable peace may permeate much of the music he composed, only rarely did he refer directly to his turbulent state of mind. ‘My life has always been so fevered that I don’t know how I have ever got any work done,’ he wrote in an unusually revealing letter of 1937. ‘And I can’t grow up, and long for home and children and settled things. Just now it is all worse than ever, and I can’t even get down to work – for all the last year it has been like this. All just a fever.’[35]

This restlessness of spirit probably explains why Bax was always on the move, never settled for very long in any one place. He did have rooms in Fellows Road which were his London base up to the outbreak of the war, and from 1939 until his death he lived in the White Horse, a village hotel in Storrington, Sussex. But he travelled ceaselessly. It seems, too, that from about this time his friends began to get the impression not only that was he drinking heavily, but that he was increasingly coming to rely on it. It is not impossible, I suppose, that one of the appealing things about his visits to the Fleischmanns in Cork was that, without any demands being made on him, he could share in simple family life – stable, domestically uneventful and, at least in comparison with his own, relatively uncomplicated. He missed these visits greatly during the war years.

‘My dear Tilly,’ he wrote in July 1943,

The year is getting on towards the time when I used to board the Innisfallen and enjoy that happy night journey to Cork, and the ever-kind welcome on the quay. I have been thinking much lately of Oysterhaven and Staigue Fort and Glengarriff – some of the happiest summer holidays I ever spent were spent among those places with you and the two Aloys-es and all my life I shall remember your affection and generosity. I am longing for the day when this wretched period of the world’s history is over and we shall all meet again on the soil of Ireland.[36]

The previous year, 1942, he was appointed Master of the King’s Music. ‘Many thanks for so kindly sending me that wire of congratulations,’ he wrote to Tilly Fleischmann.

I am glad to find that my appointment to this post seems to find favour with most of the musical world – thank heavens. It came as a great surprise to me as I imagined it would go to some important organist and even now I am not sure what it involves! However, nothing arduous, I believe.[37]

But reactions to his appointment were in fact mixed. Wilfred Mellers described it as ‘surprising and perverse’, explaining that in his creative work Bax was ‘neither altogether a contemporary composer nor representatively an English one.’[38] Although it is true that his music was still heard quite frequently, especially during the war as he was an important national figure, Bax felt that it was not always performed for the right reasons. The truth is that critical opinion was becoming increasingly unsympathetic to his particular brand of romanticism, and there can be little doubt that the discontent that hung over his final years were also due in no small measure to this. He was beginning to find himself outmoded and, in spite of the honours and outward respect, he began to feel the chill of neglect.

After the war Bax resumed his visits to Ireland. In 1946 he presided at a summer school for composers held in Dublin under the auspices of the Department of Education, something he could never have been persuaded to undertake in England, and in the same year he became external examiner in Music at both University College Dublin and University College Cork, which position he held until his death. The following year, 1947, he received an Honorary D. Mus. from the National University of Ireland, and there was a symphony concert devoted to his works given by the Radio Éireann Symphony Orchestra in Dublin, conducted by Arthur Duff, as well as a chamber concert given by Maura O’Connor and Charles Lynch. He had an inkling of this honour the previous year, and wrote to Mary Gleaves ‘if it comes off [it] will please me even more than Oxford or Durham. It would make me feel that I am taking an authentic place again in the cultural life of this beloved land.’[39] In 1950 Aloys Fleischmann, Aloys Óg that is, conducted an all-Bax concert, again in Dublin – ‘I think you covered yourself with glory and the orchestra did splendidly,’ Bax wrote to him afterwards,[40] and in 1953, the week before he died, Fleischmann conducted yet another all-Bax concert in Dublin, the one he refers to in the letter quoted at the beginning of this article.

In 1953, Bax’s examining duties at University College Cork finished on Friday, 2 October. He was due to make a speech at a dinner in Manchester in honour of Sir John Barbirolli the following Thursday, but on the Saturday evening before his departure from Cork, there was to be a gathering of some of his friends at Lacduv, the home of John. J. Horgan. Horgan had taken him for a drive to the Old Head of Kinsale earlier in the afternoon, and at sunset ‘the whole sky’, in Tilly Fleischmann’s account, ‘was ablaze with colour of every possible hue.’

Red, deep orange, yellow and far away on the horizon there was a pale blue mist. Arnold was lost in gazing at it, and John had to take him by the arm gently and remind him that we were all waiting for him at ‘Lacduv’. He enjoyed every minute of his trip to the Old Head and was reminiscing about old times, and his friends all the way back. They entered the hall, and John was just about to give Arnold a drink, when he stood up suddenly from his chair, and said ‘please take me home.’[41]

Mary Horgan immediately took him to Glen House where he was staying with Professor Fleischmann and his family. Fleischmann himself was at a meeting in town, and his wife Anne was awaiting his return before setting off to join the party at Lacduv. She suggested sending for the doctor but Bax would not hear of it. He begged her to wait until morning. Anne Fleischmann however telephoned to Dr James O’Donovan who arrived within twenty minutes, and after he examined Bax he told her there was no hope.[42] When, a day or two later, the script of the speech he was to have made the following Thursday was discovered in Bax’s room, Fleischmann thoughtfully had it copied and sent it on to Barbirolli. ‘It has been an unspeakably tragic time for us all’ he wrote in his accompanying letter, and he added that Bax’s brother Clifford and his sister ‘have expressed the wish that he be buried in Cork.’

Tilly Fleischmann informs us that a few days before his death Bax told her he intended to resign his position as Master of the Queen’s Music and to come and live in Ireland, in Cork for preference, as Dublin in his view had become too cosmopolitan. It is difficult to know how seriously Bax meant this, but perhaps even at this late stage he still hoped he could find something like peace by crossing the Irish Sea. The country never seems to have lost its allure for him as an enchanted place where he could seek to escape from the concerns and responsibilities of everyday life, and as late as 1952, fifty years exactly after his first visit, he was looking forward to the end of his duties as examiner at the University ‘so I can just relax,’ as he put it, ‘and lose myself in the Connemara dream.’[43]

Notes

1. copy of letter from Aloys Fleischmann to Sir John Barbirolli, 5 October 1953, Fleischmann Papers, Archive of University College Cork. John J. Horgan met Barbirolli when the Cork Orchestral Society, of which he was a patron and former president, presented concerts by the Hallé Orchestra in Cork in October 1952.

2. ‘Into the Twilight: Arnold Bax and Ireland’, The Journal of Music in Ireland, Vol. 4 No. 3, March–April 2004, pp. 24-29.

3. Tilly Fleischmann, ‘Some Reminiscences of Arnold Bax and how he came to Cork’, The British Music Society, Newsletter 86, June 2000, p. 34 [these ‘Reminiscences’ are undated, but were probably written sometime during the mid to late 1950s].

4. There was one other published literary work, Love Poems of a Musician, which was brought out anonymously in London in 1923.

5. quoted in Lewis Foreman, Bax, A composer and his times, London 1983, p. 123.

6. Lewis Foreman, op. cit., p. 164.

7. In the chapter ‘Music in Cork’ [pp. 268-276] in Fleischmann’s in Music in Ireland: A Symposium, Cork, 1952, 1925 is erroneously given as the year when the Father Mathew Feis was founded in Cork, [the correct date is given on p. 216], and also erroneously as the year when Bax first came to adjudicate. Nor was Bax the first adjudicator, as is also stated here. Tilly Fleischmann [op. cit.] and Aloys Fleischmann [‘Aloys Fleischmann talks to Michael Dawney’, Composer, Winter 1975/76, p. 29] both erroneously give 1928 as the year Bax came as adjudicator to the Feis. These errors have been perpetuated in subsequent writing about Bax.

8. Tilly Fleischmann, op. cit., p. 34.

9. Tilly Fleischmann, op. cit., p. 34.

10. letter from Arnold Bax to Tilly Fleischmann, 1929, Fleischmann Papers, Archive of University College Cork. Bax’s letters are seldom dated, but as Tilly Fleischmann kept most them in their original envelopes, it is usually possible to date them from the postmark. Otherwise the date is conjectural based on the contents.

11. Daily Telegraph, 4 May, 1929

12. draft of letter from Aloys Fleischmann Senior to Arnold Bax, 14 May 1929, Fleischmann Papers, Archive of University College Cork.

13. i.e. Geraldine Neeson, performing under her maiden name, Sullivan.

14. The Cork Examiner, November 22, 1929.

15. letter from Arnold Bax to Tilly Fleischmann, 24 November 1929, Fleischmann Papers, Archive of University College Cork.

16. letter from Arnold Bax to Aloys and Tilly Fleischmann, 25 December 1929, Fleischmann Papers, Archive of University College Cork.

17. letter from Arnold Bax to Tilly Fleischmann, 19 June 1935, Fleischmann Papers, Archive of University College Cork.

18. lettercard from Arnold Bax to Tilly Fleischmann, 2 September 1935, Fleischmann Papers, Archive of University College Cork. Bax’s The Morning Watchwas premiered at the Three Choirs Festival in Worcester on 4 September 1935.

19. letter from Arnold Bax to Tilly Fleischmann, 1932? Fleischmann Papers, Archive of University College Cork.

20. Geraldine Neeson, In My Mind’s Eye: The Cork I Knew and Loved, Dublin, 2001, p. 114. [Geraldine Neeson’s autobiographical In My Mind’s Eye was completed before her death in 1980, but remained unpublished at the time.]

21. Daniel Corkery, Arnold Bax [a talk given on Radio Éireann in 1943, as a tribute to Bax on his sixtieth birthday], photocopy of MS in the Fleischmann Papers, Archive of University College Cork.

22. Tilly Fleischmann, op. cit., p. 34

23. letter from Arnold Bax to Tilly Fleischmann, 1931, Fleischmann Papers, Archive of University College Cork.

24. Aloys Fleischmann talks to Michael Dawney, Composer, Winter 1975/76, p. 30

25. Letter from Arnold Bax to Tilly Fleischmann, 13 April 1937, Fleischmann Papers, Archive of University College Cork.

26. Bax did not cease all literary activity, however, although it was now of a private nature and nothing more was published. See Colin Scott Sutherland,Arnold Bax, London 1973, p. 170n; and Lewis Foreman, op. cit., 335

27. Lewis Foreman, op. cit., p. 308.

28. letter from Arnold Bax to John J. Horgan, 27 May, 1937, quoted in Aloys Fleischmann, ‘The Arnold Bax Memorial’, U.C.C. Record, Easter 1956, p. 29.

29. Daniel Corkery, op. cit.

30. Letter from Balfour Gardiner to Aloys Fleischmann [unclear whether to father or son!], 25 May 1939, Fleischmann Papers, Archive of University College Cork.

31. Earth out of Earth, which was published in 1939.

32. letter from Arnold Bax to Tilly Fleischmann, 27 December 1939, Fleischmann Papers, Archive of University College Cork.

33. Letter from Arnold Bax to Aloys Fleischmann, 1940? Fleischmann Papers, Archive of University College Cork.

34. Lewis Foreman, op. cit., p. 325.

35. quoted in Lewis Foreman, op. cit., p. 313.

36. letter from Arnold Bax to Tilly Fleischmann, 13 July 1943, Fleischmann Papers, Archive of University College Cork.

37. letter from Arnold Bax to Tilly Fleischmann, 29 December 1942, Fleischmann Papers, Archive of University College Cork.

38. quoted in Lewis Foreman, op. cit., p. 325.

39. quoted in Lewis Foreman, op. cit., p. 341.

40. letter from Arnold Bax to Aloys Fleischmann, October 1950, Fleischmann Papers, Archive of University College Cork

41. Tilly Fleischmann, op. cit., p. 38.

42. copy of letter from Aloys Fleischmann to Sir John Barbirolli, 5 October 1953, Fleischmann Papers, Archive of University College Cork.

43. quoted in Lewis Foreman, op. cit., p. 352

Published on 1 January 2005

Séamas de Barra is a composer and Senior Lecturer at the Cork School of Music.