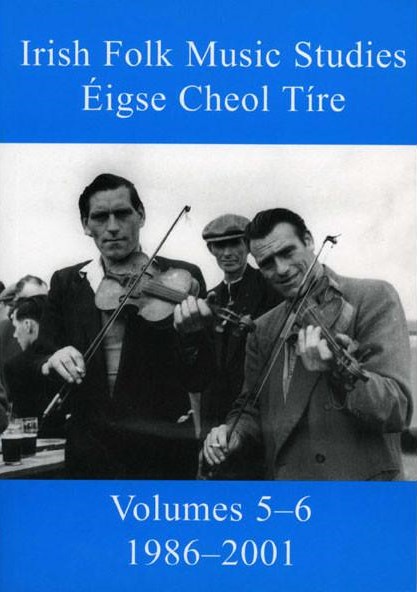

Irish Folk Music Studies/Éigse Cheol Tíre, Volumes 5-6, 1986-2001

Aside from the distinction of being the most infrequently published journal that I am aware of, the journal of the Folk Music Society of Ireland, Irish Folk Music Studies/Éigse Cheol Tíre, sets itself apart from many other academic publications in one particularly important way. Other journals often tend toward a homogeneous style of writing, largely dependent upon contemporary trends. However, in these volumes there is a refreshing lack of uniformity, and indeed this may be where it’s greatest strength lies. The variety of voices that is presented is rarely found elsewhere. Primary accounts, for example, Michael Tubridy’s description of dancing in West Clare and Dublin, stand side by side with academic discussions such as Nicholas Carolan’s examination of Philip O’SuIlivan Beare’s references to music in Ireland.

Of the five articles contained in this publication, some may logically be read in tandem. There is some similarity in the investigative work conducted by Carolan and John Moulden. Perhaps, both of these essays represent the more customary face of folk music scholarship. John Moulden traces the song text ‘The Gallent Female Sailor’ and related texts, in an effort to ascertain the origins of the protagonist and events recounted. He conducts an exhaustive inquiry, relying upon a variety of sources, and leads the reader on a folkloristic ‘whodunnit’, or more aptly ‘who was she?’ He presents a convincing case for believing that these ballads are rooted (at the very least) in ‘real’ or actual history. Nicholas Carolan also leads the reader on an investigative journey. As Carolan correctly points out, there is a frustrating lack of documentation on music in Ireland prior to the eighteenth century. This exhumation of O’Sullivan Beare’s works, more specifically the musical references contained within, is important due to this. The second of O’Sullivan Beare’s books, Zoilomastix (1625), is particularly interesting, firstly because it contains more musical comments, and also because it’s expressed aim is to rebut the aspects of the history of Ireland as written by the Welsh scholar, Giraldus Cambrensis.

Hugh Shields and Michael Tubridy both write experiential accounts of their respective subjects. Shields’ declared topic is transcription of songs (both text and at times music) in the pre- tape recorder age, However, what transpires is a wonderful, descriptive account of the process of collecting songs: the characters he met, the places he went, and perhaps, most importantly, the lessons he learned. Musical folklorists have long discoursed upon the process of their art, but Shields’ ruminations are fresh and yet evocative of a particular moment in time. Michael Tubridy also writes of particular moments in time, as he describes dancing during his childhood in West Clare and subsequent dancing in Dublin during the late 1950s and early 1960s. Current scholarship often cites The Dance Hall Act (1935) as sounding the death knell for house dances in rural Ireland, but as Tubridy recalls, house dances continued well in to the 1950s in West Clare. He also has some very interesting observations on the conflict between ceili dancing and set dancing during the 1960s. It was a time during which sets were not danced at ceilis, harking back to an earlier Conradh na Gaeilge stance, but Tubridy recalls a private club at which only sets were danced.

Therese Smith stands apart in this volume as the only ethnomusicological contributor. Her essay concentrates on the difficulties encountered when studying oral musical traditions. This is particularly challenging when teaching students with no previous experience of oral music. Given the fact that it is simply not feasible for most students to study oral music traditions in what might be thought of as their indigenous environment, Smith recommends some measures that combat the sterility of the classroom. Learning how to perform, even at a rudimentary level, she feels is paramount. Studying a traditional Irish instrument has long been part of the curriculum at the Music Department in UCC, for all music students, and it certainly contributes hugely to the understanding that students gain, not just of Irish traditional music but also other traditions. Smith draws an obvious, but sometimes ignored, conclusion that ‘to be musically literate, increasingly as we move into the twenty-first century, is paradoxically, to be orally educated…’ (p. 25).

These volumes were a long time in the making, fifteen years in fact, but the essays contained within do reflect the wheels of folk music scholarship turning, while keeping a watchful eye on the past. Several book and record reviews, plus a select bibliography and discography, are also included.

Published on 1 May 2002

Dr Méabh Ní Fhuartháin is Head of Irish Studies at the Centre for Irish Studies, University of Galway.