A Long Drive from Limavady

‘The Londonderry Air’ enjoys a fame that is unique in Irish music. Such is its appeal that it has been recorded many times over the years by artists as diverse as Paul Robeson, Glenn Miller, Judy Garland, Johnny Cash, Elvis Presley, Kiri Te Kanawa and Beaker from Sesame Street. While few would contest its musical quality, no such consensus surrounds its musical provenance, which has long been shrouded in mystery and is the subject of an ongoing debate.

This has centred on both the origins and the nature of the melody. Why did it suddenly emerge, as if from nowhere, in the middle of the nineteenth century? Is it really a traditional tune? Or a romantic adaptation of an older melody? Or even an original composition? In seeking an answer to these questions a number of clues have now emerged which point far beyond the shores of Ireland to England, Continental Europe and even Australia.

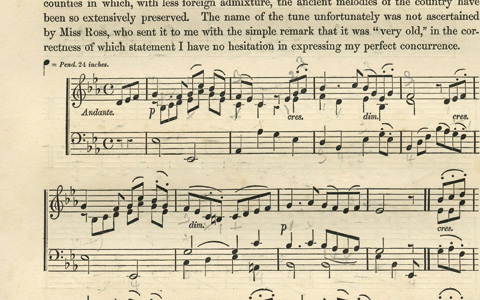

The roots of the controversy may be found in its original publication in George Petrie’s The Ancient Music of Ireland – Volume 1 (1855). Petrie merely stated that it had been placed at his disposal by a Miss J. Ross, who had sent it to him from Newtownlimavady ‘in the county of Londonderry’ with the remark that it was ‘very old’. Neither Petrie nor Jane Ross ever revealed where or when she had heard the melody, who had played it to her, or its original title. The description ‘The Londonderry Air’ only appeared in 1894 when she was already dead. The words ‘Danny Boy’ were not added until 1913, having been previously written for another melody by the English songwriter Fred Weatherly.

Newtownlimavady, or Limavady, as it is now known, was a small rural town in the north-east of Ireland with no particular claim to fame, musical or otherwise. It dated from the Plantation of Ulster in the early seventeenth century. Most of its inhabitants were, therefore, of Scottish descent, with the original Gaelic Irish having moved to the more mountainous regions of the county.

The Ross family was by no means poor. Jane Ross’ father had first married an Elizabeth McCausland, and then, on her death, his cousin Jane Ogilby, Jane’s mother. Both families were prominent in local society. Jane (1810–1879) was the first of six children. She was followed by Elizabeth, William, Ann, Theodosia and John in that order. She spent her first thirteen years at the Lodge, a large house with extensive grounds at the end of the Main Street in Limavady. She then moved to 51 Main Street, where she remained with her sisters until her death. None of them married. Both houses are still visible. Her brother William (1814–1891) and sister Theodosia (1819–1875) were to share her interest in folk music.

The air’s fame dates from its first recording in 1915 by the renowned opera singer Ernestine Schumann-Heink. This seems to have inspired the plethora of hitherto forgotten memories that have now woven their way into its legend, and are often presented as ‘facts’ with little apparent evaluation. Chief among these is the tradition that it was written down by Jane from the playing of a violinist outside her home in the Main Street.

The actual source of this tradition is difficult to locate. The first written mention of a Limavady street musician appears to have been made in a letter to the Sunday Times in 1928 from a Major Riky. In it, however, a Miss Honoria Galwey, and not Jane Ross, is claimed to have been the recipient of the tune. It should be noted that this was already some seventy-five years after the actual event. Since then two different candidates have been proposed as the fiddler in question – one named McCormick, in a letter of 1934 to the local historian Sam Henry, and the other named McCurry (1830–1910), more recently, in the writings of Jim Hunter. The claims of both depend on distant family memories, and we also have to consider the knowledge that they both belonged to the Scots Irish rather than the Gaelic tradition from which the melody most probably emerged, and that neither would have been much more than twenty years old at the time concerned.

The earliest written account of the air’s discovery by a member of the Ross family gives a very different version of its origins. This was quoted by Brian Audley, and may be found in the archives of Sam Henry. In it, the Rev. William Manning (grandson of Jane’s brother William) states that his mother was informed by Jane herself that her brother William had been the first to hear the tune, and had told her where to find ‘the mountain cabin where he heard it played on a fiddle as he passed’. After ‘a long drive from Limavady’ she met ‘a very old man’ from whom she copied the melody, and learned that his father had got it from a harper (a traditional Irish harpist). This was said to have happened ‘after the severities of the famine’, which could have meant after 1848 in that area of Ireland.

Since this was a written account from a presumably reliable source – an Anglican clergyman – supposedly quoting the words of Jane herself, it deserved to be taken seriously. And yet it had been consistently ignored in favour of a local oral tradition. It was time for a serious investigation, beginning with Jane’s brother William.

The family gravestone in the grounds of the Anglican Parish Church in Limavady indicated that William had, in fact, been a Canon William Ross. A search of clerical records revealed that from 1848 to 1850 he was Curate of Upper Cumber which was situated between Dungiven and Derry, and that in 1850 he became Vicar of Dungiven, some ten miles south of Limavady, where he remained until his retirement in 1886.

The Rev. William Manning’s account was, therefore, entirely credible. From 1848 onwards his grandfather had been resident in a mountainous region of County Derry where the Gaelic tradition remained strong. As a clergyman travelling around his parish he would have passed many ‘mountain cabins’. And the area would have been a ‘long drive from Limavady’. There was thus real evidence that the melody had, indeed, been first copied down in the mountains around Dungiven, and not on the Main Street of Limavady as is usually maintained.

The mention of a harper in the Rev. William Manning’s account adds credence to this belief. Denis O’Hampsey (c. 1695-1807), the last of the great Irish harpers, had lived in Magilligan a mere twenty miles from Dungiven, and had included in his repertoire a melody that is generally acknowledged to be the forerunner of ‘The Londonderry Air’. It was called ‘Aislean an Oigfear’ or ‘The Young Man’s Dream’. It had been notated by the organist Edward Bunting on a visit to the elderly harper’s home in 1796, and, as Hugh Shields pointed out in 1979, closely matches ‘The Londonderry Air’ in much of its melodic shape, though written in triple time and lacking the final higher section.

If, however, ‘Aislean an Oigfear’ was indeed the musical origin of ‘The Londonderry Air’ it had changed significantly by the time it was sent to Petrie. Could this have happened naturally with its repetition over the years? Some, such as Audley, have claimed it could, but such an explanation is no longer likely. The Ordnance Survey of the Dungiven area in the 1830s contains a catalogue of songs that had been compiled in 1834 and given to Petrie himself. No. 30 was ‘The Groves of Blarney’, ‘as known in Dungiven’. As Petrie observed, ‘The Groves of Blarney’ was simply another version of ‘Aislean an Oigfear’. The melody that O’Hampsey had played to Bunting was, therefore, still being sung in Dungiven in 1834. It is reasonable to assume it was this same melody that Jane Ross copied down some fifteen years later. ‘Natural’ changes could not possibly have occurred in so short a period. It should be noted that there is no mention in the catalogue of ‘The Confession of Devorgilla’ (‘Oh Shrive me Father’) which was claimed by Audley in his article of 2000 to have mutated ‘naturally’ into ‘The Londonderry Air’.

What then could account for its sudden transformation? There was only one possible explanation – it had been changed by a human hand. And the changes must have involved Jane Ross herself.

This is not a new suggestion, but dates back at least to Havergal Brian, the English composer and critic in 1935. He noted that ‘The Londonderry Air’ is not in a traditional Irish metre, and was puzzled by its wide vocal range, and by its sudden appearance without the close variants one would have expected with a genuine folk tune. Hugh Shields, an expert in the folk music of the area, also expressed doubts about its provenance, and suggested it was an adaptation of an older melody for a Victorian drawing room. With its soaring melodic lines and expressive appoggiaturas it certainly had the romantic characteristics of the classical music of the day. So too had Jane Ross’ comments on its performance as recorded by the Rev. William Manning – the opening was to be played ‘with melancholy’ with ‘a natural and appropriate reaction for the last part’.

While Manning’s account offers no explanation for the changes, it does explain two of the mysteries surrounding the air. First, Jane Ross’ statement that it was ‘very old’. If it had originated with O’Hampsey it would most certainly have been ‘very old’ as she claimed. And second, her surprising reticence as regards its origins. Since she knew Petrie had been working for the Ordnance Survey in the Dungiven area and had been collecting its music himself, she realised he would most certainly have known the original melody and would have found the changes startling, to say the least. She could not, therefore, reveal anything that might link ‘The Groves of Blarney’ to the melody she sent to him.

There was now ample evidence to suggest that ‘The Londonderry Air’ was based on an older Irish tune from the mountains around Dungiven. In its present form it was not, therefore, very old. But the fundamental mystery remained. If the ancient Gaelic melody had not mutated ‘naturally’ into the polished, romantic air that was published by Petrie, who had been responsible for its transformation?

While Jane Ross might be the obvious suspect she had never demonstrated such a creative ability elsewhere in her life. She is not recorded, after all, as having ever composed a note of music. Could an amateur pianist in the Limavady of the mid-nineteenth century really have been responsible for the creation of a melody of such quality and romantic sentiment? It seemed unlikely, without some assistance.

After much reflection there was one possible explanation. The changes could have happened under the influence of a professional musician, well versed in contemporary trends. Since there was no evidence of Jane having studied abroad, this musician could have been resident in Limavady at the time.

It was a highly implausible theory, and the possibility of finding such a person seemed remote. But such a person did exist. His name was Edward Frederick Christian Ritter (1817–1881). He was employed as music teacher to the Alexander family, landed gentry on the outskirts of Newtownlimavady, who at the time were living in Ballyclose House, an ancient residence at the end of the Main Street in Limavady, a short distance from the Ross sisters.

The Alexanders had much in common with the Ross family. They were members of the same Parish Church. They belonged to the same social stratum, and appear to have been linked by marriage in the past. They also shared an interest in music. And it was to this Alexander home that Edward F. C. Ritter arrived, probably around 1848, as tutor to daughters Anna (1828–1858) and Jane (1830–1903).

According to the story, as related on the Roe Park website of 2009, he was hired from Alsace-Lorraine, fell in love with his younger pupil Jane Alexander, and eloped with her to Australia ‘where they made a vast fortune in the gold trade’.

The basic veracity of the story was soon established. Edward F. C. Ritter had, in fact, been born in Prussia. He had married Jane Alexander on 31 August 1850 at ‘St. Marylebone, Middlesex’, and an Australian naturalisation certificate in his name was dated 4 June 1851. The couple had settled in St Kilda near Melbourne and he became a gold trader with his own office. They eventually returned to London, where he died in 1881.

Some time after his death, his widow came back to Limavady, where her eldest son, J. E. Ritter (1853–1901), inherited the Roe Park estate in 1887, and is still remembered for his experiments with hydro electricity. The final proof of the story was uncovered in the graveyard of the Parish Church when the removal of a century of moss from an ancient tombstone revealed the name of ‘Jane Ritter, wife of E. F. C. Ritter’. Jane Alexander had returned to the town from which she had eloped so long before. Her memorial was beside that of Jane Ross and her family.

As a musician from Prussia Edward F. C. Ritter would most certainly have been conversant with the latest musical fashions. The Ritters were, after all, a well-known musical family, as the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians attests. He might also have been aware of the Irish folk songs that were becoming increasingly popular in continental Europe. Had not both Beethoven and Mendelssohn set ‘The Last Rose of Summer’? Of one fact we can be certain – his arrival in rural Limavady would not have gone unnoticed.

A clear picture had now emerged. In 1848 or 1849 William Ross heard an interesting tune in the mountains around Dungiven. He told his sister Jane. She travelled to meet the musician and copied down the melody. At about this time Edward Frederick Christian Ritter arrived in Limavady. Given their common interests and status it seems inconceivable their paths did not cross. It is entirely logical, therefore, to infer that the arrival of Edward F. C. Ritter was an influential event in the lives of the Ross sisters. As regards the extent of his influence, however, we can only guess. The possibilities are endless. Tempting as it is to speculate, such speculations had to be resisted. We simply do not know. It could all be a coincidence.

With the excitement of the elopement and her brother William’s marriage to Caroline Matilda Trelawny-Collins of the Ham estate at Plymouth the following year, the melody probably passed from Jane’s attention until she heard of Petrie’s Society for the Preservation and Publication of the Melodies of Ireland. This had been founded in 1851 and was advertising for material to publish. By 25 October 1853 it was in Petrie’s hands.

The original melody had, by then, been ‘modernised’ to fit the style that was popular in the drawing rooms of the musically literate. In this ‘modernisation’ the musical influence of Edward F. C. Ritter may have borne fruit.

Such adaptations were, of course, common at the time and popular with the public. Both Bunting and Petrie had added piano accompaniments to their melodies, as had other classical composers in their arrangements, while Thomas Moore had also added his own poetry. Any ‘modernisation’ of ‘The Londonderry Air’ was, therefore, entirely in keeping with contemporary practice.

As a result of this research, new light has been cast on the likely origins of the air, and a new line of enquiry has been opened into its transformation into the melody we all recognise. The exact truth will never be known, but Jane Ross’ contribution to the formation of ‘The Londonderry Air’ should be applauded, not condemned. She could not have dreamt of the fame that would ultimately await her melody, nor the controversy that would surround her actions. We should be glad this was so. Without her contribution ‘Aislean an Oigfear’ would have remained unknown. In its successor, with its romantic overtones and fusion of Scots Irish and Gaelic culture, we have a melody that is rightly celebrated throughout the world.

Further research is needed, and may yet reveal more details of the relationship between the Ross sisters and Edward Frederick Christian Ritter, but it will be hampered by the fact that the descendants of both families are long since dispersed in England. Some evidence may yet be hidden in Australia, however. It has always been assumed that the gold prospectors from whom Margaret Weatherly heard the melody in Colorado in 1912, prior to sending it to her brother-in-law Fred, were from Ireland. It has been suggested, however, that they were Australian. Edward Ritter made his fortune as a gold trader in Australia. Was this a coincidence? Was it also coincidental that the earliest setting of the melody by a composer was by the Australian, Percy Grainger, in 1902?

Published on 1 June 2010

Brendan Drummond is a former teacher and writer on music education. He is currently a music examiner for Trinity Guildhall, London.