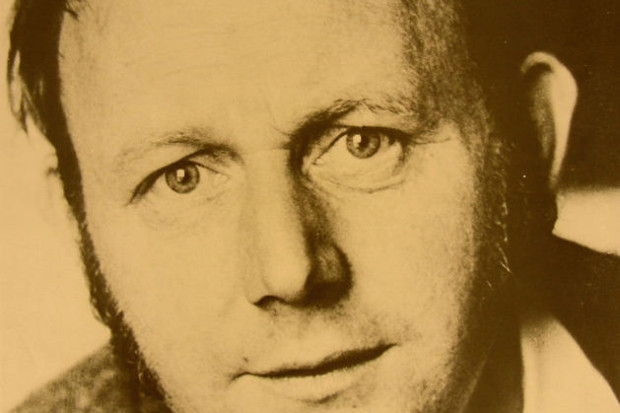

MacMahon from Clare – Tony MacMahon

Tony MacMahon

MacMahon from Clare (MACCD 001)

‘I have chosen to play you a lament first because, in our own time, the loss of love is one of the things that afflicts all suffering mankind.’

This is how Tony MacMahon introduces ‘An Buachaillin Ban’, the first track of his new CD, and over the last few months since its release I have been mulling this sentence over. The dual meaning is one reason it sticks with me; possibly he is referring to individual scenarios, as all people at one stage or another suffer the loss of love, but I take great interest in the alternative. Is Tony MacMahon, in the preamble to his performance, which was recorded at the Boston College Gaelic Roots Festival in 1999, actually contemplating the idea of a widespread misery that affects the entire race as it moves through another millennium? This notion halts me, for it is so rare to hear a musician utter such reasons for playing music. Imagine being so moved by ‘the loss of love’ and ‘suffering mankind’ that you would play music!

Perhaps I am sounding ironic. Isn’t it such noble, human emotions that moves all musicians to play? Well, in theory, yes, but rarely do those motives come so passionately to the fore, seldom does a musician manage to excavate so deeply down into emotion that they create such a direct line for the listener – out of the receiver’s world, into the music, and back out again into a renewed world. That, I sup pose, is genius, and that is also why it is difficult to listen to this album without being made aware by MacMahon of the burdens the world carries. MacMahon From Clare is the largest call to humanity that has come out of Irish traditional music for years.

And why wouldn’t it be so, for this music comes from a figure who is, in a sense, both tragic and a cause for our celebration. As MacMahon has said himself, he had ‘gone away’ from music for some time. This was not always a physical absence, although the first time I met him, aware of the reputation as a player that preceeds him, he was quick to say that he ‘hadn’t played in three months.’ His real absence, I think, and I can only deduce this from snippets of conversations and observation over a few years, was a mental and spiritual one. On one occasion, I overheard MacMahon despair about Irish music, telling a North-African multi-instrumentalist how their music ‘puts us in a big hole in the ground’. What MacMahon, I think, was despairing at was the globalizational tendency towards predicatibility in music, towards putting music in a box (metaphorically speaking of course). MacMahon’s way of understanding, thinking, and communicating through music has been at times so far removed from our cultural climate that he has had no alternative but to distance himself from it.

But he could not abandon it, and his work as a producer in television, through The Pure Drop and The Blackbird & the Bell, among many others, appear as MacMahon’s attempt to inject the necessary discernment back into Ireland’s cultural life, if only for it to become intelligible again, and reconnect Irish people with a musical integrity and creativity that was once natural to them.

I once glimpsed a I970s music programme that MacMahon presented. How different his presentation of the music was to much practise today; using words like ‘discernment’, ‘fragility’, and ‘tenderness’, Ireland and its music were made appear so noble, so strong far away from the Ireland now embedded with the ‘For Sale’ sign.

MacMahon from Clare is both a retrospective and a presentation of new recordings; all of the latter are essentially live in that they weren’t recorded in a studio – MacMahon’s house in the Liberties being used instead. There are tracks many years old, although never previously released in this format, both with MacMahon solo and also playing duets with James Kelly, Peadar Mercier, Joe Cooley and John Beag Ó Flatharta.

I do think the newer recordings are the highlight however. I listen often to the four sets of marches, two of them with Barney McKenna striking this raw, human sound behind MacMahon; marches, always tinged with resilience by nature, are pushed further here, with boisterousness and at the same time union and brotherhood.

MacMahon is widely acknowledged as a pioneer in playing slow airs, and many will be expecting this if nothing else from the CD; he has included five here, each allowed to illustrate some or other aspect of MacMahon’s worldview; the five stand apart from the rest of the CD as a pentagonal view of the musician’s approach to melody, something in which there is years of listening.

MacMahon’s rendition of the set-dance, ‘The Garden of Daisies’, is, I think, the apex of this recording. The penultimate track on the album, it is an eruption and a deconstruction of art. I have listened to this track many times and still have not had the whereabouts to catch how many times the tune is played or where the first and second parts start or finish. It is a carousel of music, with MacMahon taking deep breathes every now and then and boring down into the tune, releasing notes and cuts with flicks and splutters.

There is tragedy in this music, and, from time to time, Tony MacMahon strikes me as a tragic figure. I listen to the talk of musicians, and often hear him demonised, dismissed, and I hear an anger and impatience in their voices towards him. How do ideas and music that are essentially a benevolent expression of affection for a country and a people offend so many? MacMahon has stood on toes, sure, but how does this overrule the quality of this musician’s music?

Nonetheless, as the tide turns and Ireland tires of the Celtic Tiger’s glitter, we can already see evidence that MacMahon is being looked to and his stances against commercialism respected. He will prove even more important as time goes on, as his ideas and music comes under closer scrutiny.

In MacMahon Fom Clare we have, I think, his most complete statement. It fills in gaps that television programmes and interviews can’t. What is really captivating about this recording, however, is not that he might answer old questions about himself, but that he himself poses some new ones.

His drama/music production, The Well, which ran as part of last year’s Dublin Theatre Festival appeared to me as MacMahon’s potshot at all the big questions in traditional music, and also in the wider sphere of what ‘tradition’ can really mean to us. But I don’t think those questions were resolved. In MacMahon from Clare, he is no longer pondering. He has made his decisions and he is out to inspire us, to ask us to embrace the world, rattle it, and use every iota of knowledge we have to begin questioning where our world is taking us. He has put that challenge to the listener, and MacMahon Fom Clare is an astounding impetus to do so.

-

First published in JMI: The Journal of Music in Ireland, Vol. 1 No. 2 (Jan–Feb 2001), pp. 16–17.

Published on 1 January 2001

Toner Quinn is Editor of the Journal of Music. His new book, What Ireland Can Teach the World About Music, is available here. Toner will be giving a lecture exploring some of the ideas in the book on Saturday 11 May 2024 at 3pm at Farmleigh House in Dublin. For booking, visit https://bit.ly/3x2yCL8.