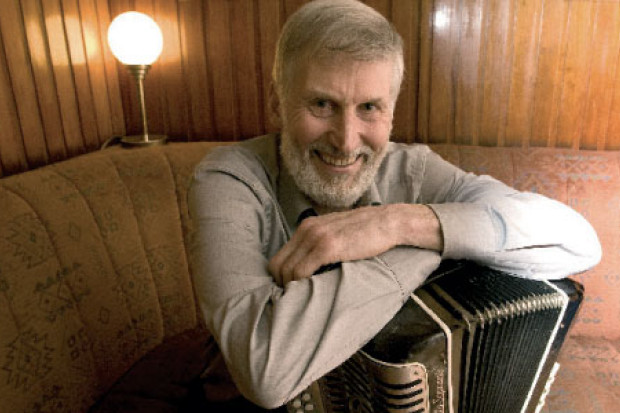

Uilleann pipers Johnny Doran (far right), Pat Cash and Cash’s son, in Dublin in 1941.

The Piper's Story Over Three Centuries

The Wheels of the World: 300 Years of Irish Uilleann Pipers is a large, sprawling book, and somewhat like Colin Harper’s book with Trevor Hodgett, Irish Folk, Trad and Blues (2004), draws together a diverse collection of profiles, interviews, archive material, tunes, and reminiscences. This is made clear in the introduction, so that although from the title you might expect something akin to a historical overview or survey, the book has a flow and direction that’s more like a session, as Harper moves from subject to subject seemingly as the mood takes him – or rather as is suggested by their connection with Belfast piper John McSherry, who helped initiate the project.

McSherry’s own story and tunes – some old, some newly-composed – bookend this volume. The transcriptions (by John Riddell, himself a piper) are exceptionally detailed in terms of the ornaments used, but don’t include the variations, so they’re a half-way house between the Borgesian detail of Pat Mitchell’s piping books and a clean outline transcription. Given the praise included in the first chapter for McSherry’s ability to create and to extemporise, it’s a pity that one or two of the transcriptions didn’t illustrate this.

McSherry’s telling of his own journey is engaging, beginning with his connection with the pre-revival piping tradition through his meetings with the Fermanagh piper Seán McAloon, who was a source of piping lore and advised him on his playing. He also, like many musicians growing up in the later part of the revival, learnt much from the recordings of other pipers. Marcas Ó Murchú was a particular influence here, as his knowledge and collection of recordings was shared with McSherry. All this was internalised through hard practice, and backed up through a busy session and gig lifestyle; almost in the manner of the travelling pipers of the previous century, McSherry toured the country playing in pubs and following the festival scene, getting gigs whenever the opportunity arose. His narrative about his later career reveals a lot about the range and the musical flexibility required of professional traditional musicians today. It’s also useful in its transparency about the nuts and bolts of the contemporary music industry, and how musicians have to respond to a model that has essentially been broken by streaming services.

From here on in the material is more directly Harper’s, and the chapters fall into a number of categories. The most entertaining and revealing chapters are the profiles of individual pipers, because of the amount of commentary by musicians on themselves and on other musicians. The interviews often convey a deeply felt conviction about the importance of tradition and of their predecessors; for example, Finbar Furey notes the importance of Seán McAloon as an influence, while also relating how Felix Dolan and Willie Clancy were regular visitors to his household, where ‘they’d play the pipes all night… And there’d be sheets of music on the table where they’d been scribbling out bits of music’. Alongside this is the recognition that pipers need to cultivate an individual identity, seen vividly where Paddy Keenan says of his own music that his playing of a tune is ‘purely an expression of me at that moment’. There’s a good deal of new interview material here on these more recent musicians (the Fureys, Liam O’Flynn, and Paddy Keenan), although quite a bit of it is focused on their respective bands, especially Planxty and the Bothy Band. Perhaps too much, as sometimes the narrative moves quite far away from the piper in question in its detailing of the ins and outs of concerts, recordings and personnel changes.

Letters and broadcasts

This style of profile is less effective in the chapters on the more historical figures; what is direct and lively in the previous chapters appears somewhat artificial, in that old interviews and printed sources are presented in indented quotes, in the same style as material which is from new interviews. The profiles are fine in themselves, without contributing a huge amount of new material. What’s more valuable are the chapters that survey archive material concerning Séamus Ennis and Leo Rowsome’s relationship with the BBC. The Rowsome chapter provides excerpts and short commentaries on letters (with their associated replies) from Rowsome to the BBC, illustrating his persistence in requesting radio appearances. Often Rowsome was attempting to arrange additional work when he was in London: in 1931 for instance he wrote that ‘Should the opportunity arise for including me in your programmes I shall be very grateful… I will be performing at the Queen’s Hall, London, on March 17 and have broadcast from Dublin frequently’. Despite being frequently declined (a memo noted that ‘This man still goes on trying!’), Rowsome did appear on some early experimental television broadcasts in the 1930s, and on a number of radio broadcasts; unfortunately the source material held by the BBC is uneven, as there are no corresponding letters for these early television appearances.

The section on Ennis’ broadcasts is very substantial, and contains a wealth of detail on both actual and planned programmes with the corporation, including fees, commentaries on the proposed scripts and performances, and additional contextual material. Occasionally more clarity in the commentaries on the records would help, as it’s not always clear where these recordings took place. The records illustrate the breadth of Ennis’ activities for the BBC, which include a talk on South African kwela music, appearances on radio dramas and documentaries, and more extended series, including the landmark As I Roved Out. Included in the chapter are details of his RTÉ television appearances, although it’s incomplete due to what Harper describes as imperfections in the RTÉ databases. A fuller listing of these, and indeed of Rowsome’s broadcasts on Raidió Éireann, would have helped further contextualise these records.

The end of the book returns to more contemporary issues, with chapters on piping in Ulster and on Brian Vallely and the Armagh Pipers’ Club, with shorter sections on figures like Wilbert Garvin, Willie Clarke, and the McPeake family of Belfast. As with the profiles of Ennis, Clancy and Rowsome, a lot of the direct quotations are taken from previously published articles; sometimes these are very long, and strung together with the briefest of connections. While it does allow the musicians’ voices to emerge, expressing a real consensus about the transformation that has taken place in piping in Ulster over the past decades, at the same time it makes for a disjointed read.

The least effective section of the book, or perhaps the most out of place, is the chapter on piping before 1900, which is too fragmentary and disjointed; here the relaxed style of writing feels misplaced, jarring with its more distant subject matter. There’s undoubted enthusiasm for the subject here, but the range of material consulted isn’t as comprehensive as it might be, and there are gaps in the narrative (for instance, the comment that there was a ‘brief flurry of interest in the pipes back in Ireland during the “Gaelic Revival” of the 1890s’ is far too throwaway, even if the period is looked at later in the chapter). There is also an odd misreading of the famous passage by Giraldus Cambrensis (Gerald of Wales), which Harper suggests might refer to a type of pipes or piping. Joan Rimmer, Alan J. Fletcher, and Leith Davis among others have provided detailed comment and analysis on this text, and all translations or commentaries I checked are in agreement that Giraldus ascribed two instruments to the Irish, the harp (cithara) and tiompán (tympanum), and that this passage tries to describe the music of the harp.

One further aspect of the writing style deserves further comment; Harper’s frequent comparisons to rock and blues. Johnny Doran’s recordings ‘equate to Elvis Presley’s influence… on the course of popular music’; both Finbar Furey and Doran are described as ‘the Jimi Hendrix of the pipes’, while Doran is also ‘the Robert Johnson of the pipes’; O’Farrell (the compiler of the early nineteenth-century O’Farrell’s Pocket Companion for the Irish or Union Pipes) also ‘bears comparison to Robert Johnson’; the music of the pipes ‘in great part, is the blues’; and Willie Clancy is compared to Mississippi John Hurt. Such comparisons, while understandable, are always doomed to be flawed, and signal a lack of analysis of the music and the musicians on their own terms.

Harper’s passion for his subject is undeniable, and his profiles, his compiling of archive material, the discography, and the wealth of interview material amply demonstrates his zeal and dedication to the topic. Unfortunately this closeness to the subject means that Harper too often writes as a fan, without sufficient critical distance or analysis of the material. In summary, then, this is a book more for the general reader than for someone already informed about the subject, although it does contain some new material, and may be more amenable to dipping in and out of for individual chapters rather than reading it in its entirety.

The Wheels of the World: 300 Years of Irish Uilleann Pipers by Colin Harper with John McSherry is published by Jawbone.

Published on 8 September 2015

Adrian Scahill is a lecturer in traditional music at Maynooth University.