The Suffering Ducks

Or, more accurately, delivered in a staccato Belfast accent, ‘The Sufferin’ Ducks’, the name of a tune played by the Belfast flutists Harry Bradley and Michael Clarkson on their forthcoming CD, The Pleasures of Hope. I’ve just been listening to a demo of it, courtesy of Michael. The music is hard, punchy, driving, full of devilment and ‘crack’ if not craic, and I’m wondering how that characteristic Belfast flute sound has come about in what, in terms of the long run of traditional music, seems a comparatively short time, maybe thirty or forty years.

In the mid-1960s there were, as far as I know, only two flute-players of any prominence in Belfast, Tom Ginley and James MacMahon, whose music would have been at opposite ends of the spectrum in terms of repertoire and technique; indeed, they played different instruments. Ginley, a native of Belfast, played a silver Boehm-system flute and was fond of tricky hornpipes, tunes beyond the ken or inclination of most traditional players. I never heard James MacMahon play his fabled ivory simple-system flute, but I gather his style would have been typical of his native county of Fermanagh, and a lovely jig attributed to him on Charlie Piggot and Gerry Harrington’s CD The New Road would seem to bear that out.

In any case, traditional music in Belfast then had a relatively low profile. Ceili bands, sometimes of a rudimentary nature in which an accordion bore the melody line, played in alcohol-free halls. By all accounts there were sporadic house sessions, not wholly confined to Catholic areas. Indeed, in the late 1950s – an interesting reflection of Francis O’Neill’s promotion of music in the Chicago police force of the 1890s – there was a session in the RUC station in Brown Square, in which the fiddle-player Sean McGuire took part. The sectarian perception of ‘Irish’ and ‘Ulster Scots’ music had yet to come, and was certainly entirely absent in the folk revival of the 1960s, a milieu in which English, Scottish and American folk mingled in happy promiscuity with the music of this island. The music of The Dubliners, for all that their repertoire included a good few old rebel songs, was appreciated by all, and the banjo-playing of Barney McKenna in particular hit a special chord with Belfast musicians. Maybe the percussive, rivet-gun attack of that instrument – ‘tuned spoons’ as it has been dubbed – was a musical equivalent of the Belfast accent. And maybe that banjo aggression found its way into the flute-playing.

At any rate, most of the traditional flutists I first heard, among them Leslie Bingham, Clive Kinghan and Brian Bailie, were Protestant. Later I got to hear Cathal McConnell playing in the original Boys of the Lough with Robin Morton and the great Fermanagh fiddle-player Tommy Gunn. Mrs Gunn, as it happened, ran a B&B in Botanic Avenue which became a notorious ceili house for visiting and local musicians, and the flutists Desi Wilkinson and Gerry O’Donnell recall how those sessions led them to explore the music of Fermanagh, which in turn led them to the hardcore flute-playing zone of Leitrim and Sligo. And I think both Harry Bradley and Michael Clarkson would attribute a good deal of their approach to the instrument from the hard-hitting style of Peter Horan, Patsy Hanley and Packie Duignan, to name some. But it is also evident that the flute band tradition, be it Orange or Hibernian, has had an impact on their music, as epitomised by ‘The Suffering Ducks’.

The tune in question comes from Sam Murray, whom I first met in about 1965, then a long-haired guitar and concertina player with a dapper line in charity shop clothing who later turned to the uilleann pipes and the flute, and is now known as one of the best makers of traditional flutes in these islands, if not the world. Now resident in Galway at the Old Forge, New Road, his previous workshops in Belfast had equally resonant addresses – Steam Mill Lane off Tomb Street, and Exchange Place. Galway’s gain is our loss. Sam’s workshop was a forum for all kinds of exchange, be it swapping tunes, instruments, scandal or anecdotes; a fount of information, be it concerning Middle Eastern rugs, old ivory, the relative virtues of boxwood as opposed to African blackwood or cocus, Russian icons, good furniture, food and fine wines. Lately he’s got into old manuscripts and vintage watches. All things well made. He’s deeply concerned with the craft and personality of things, and how tradition bears that personality across the generations.

‘The Suffering Ducks’ came to Sam from his father, a member of the Soprani Accordion Band in Belfast’s York Road area, who played it as a kind of anthem, a memory of the fact that many Catholics in the area had been forced from their homes in the Troubles of the 1920s and later. The title is ruefully ironic; the tune is a jaunty march, almost a joyful swagger. Bradley and Clarkson play it on shrill band flutes pitched in F full of attack and crack, and you could almost take it as an Orange tune. I don’t know if you have to know the history of a tune to appreciate it fully, and you can certainly play it just for the beauty of the notes, but the story does add another layer of meaning. In this case it’s doubly ironic that Sam left Belfast for reasons not entirely unconnected to the ongoing sectarian strife which affected his home in an interface area of North Belfast. He is himself perhaps a kind of Suffering Duck. So it goes through the generations.

Music leads us both into and out of ourselves. As I have sketched it, the folk music scene of the 1960s seems a golden age of cross-community participation. Maybe I’m seeing it through the rose-tinted binoculars of nostalgia. But I think it is an unassailable fact that folk music or traditional music, call it what you will, has always been open to outside influences, to rhythms and cadences beyond the immediate range of its practitioners, as demonstrated, to take but one example, by Andy Irvine’s taking the bouzouki into Irish music. There is no such thing as a purely Irish instrument. Even the uilleann pipes have parallels in other cultures. Music is made with whatever is at hand, whatever becomes available at the time, be it Italian Paoli Soprani accordion or English Rudall & Rose flute, and musicians are always curious to try their hand at something else. They’re an eclectic bunch. In the course of writing this article I was gratified to learn from his website that Harry Bradley is learning the American old-timey five-string banjo. I love the drive and get-up-and-go of old-timey music, as does Desi Wilkinson, who recently sent me a demo of a CD featuring himself, accordionist Máirtín O’Connor and the old-timey musicians Frank Hall and Lena Ullmann (fiddle and banjo). The next instalment of this column will be called ‘The New Rough Deal’, and will examine the links between Irish traditional and American old-timey music.

Published on 1 April 2009

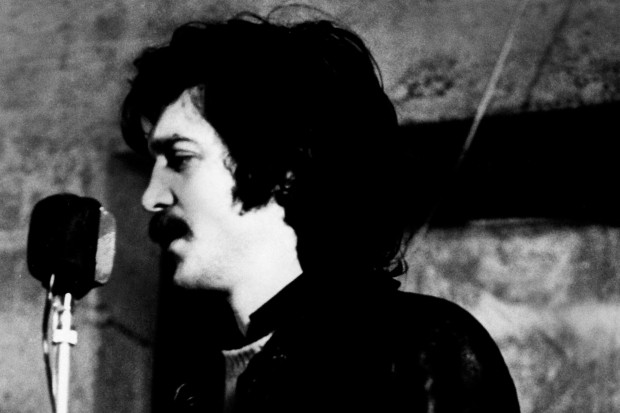

Ciaran Carson (1948–2019) was a poet, prose writer, translator and flute-player. He was the author of Last Night’s Fun – A Book about Irish Traditional Music, The Pocket Guide to Traditional Irish Music, The Star Factory, and the poetry collections The Irish for No, Belfast Confetti and First Language: Poems. He was Professor of Poetry at Queen’s University Belfast. Between 2008 and 2010 Ciaran wrote a series of linked columns for the Journal of Music, beginning with 'The Bag of Spuds' and ending with 'The Raw Bar'.