You Kept Your Promise

If you look really closely at the after-show party at the end of the Irish Tour ’74 film, you just might spot its director Tony Palmer as he admits to ‘joining in’ on the Leadbelly classic ‘Goodnight Irene’. He appears after Rory tries to encourage Tom O’Driscoll to join in the singing, and just before Mick Daly of the Lee Valley String Band comes into shot. I spoke to Tony recently about how he came to film Rory and where he first saw the guitarist.

Palmer first saw Rory play with Taste at the Cream farewell concert in 1968 at the Royal Albert Hall, which he filmed. ‘I was very impressed with Taste. In fact after the first set – there were two shows that day – I went and complained to Robert Stigwood, saying don’t you think that we should record them [Taste] as well. No, he said, so unfortunately we didn’t film it.

‘But I was very impressed by the band and woke up to Rory Gallagher’s presence as it were and then began to follow him. Quite out of the blue, in the summer of 1973, his brother Donal approached me and said Rory was going on this tour and would I be interested in making a film. I said absolutely, of course. So although by then I had left the BBC I still had good contacts and went back to Omnibus, which was then the main arts programme on television. I suggested a programme on Rory and they said yes please so that’s how the project was initiated.’

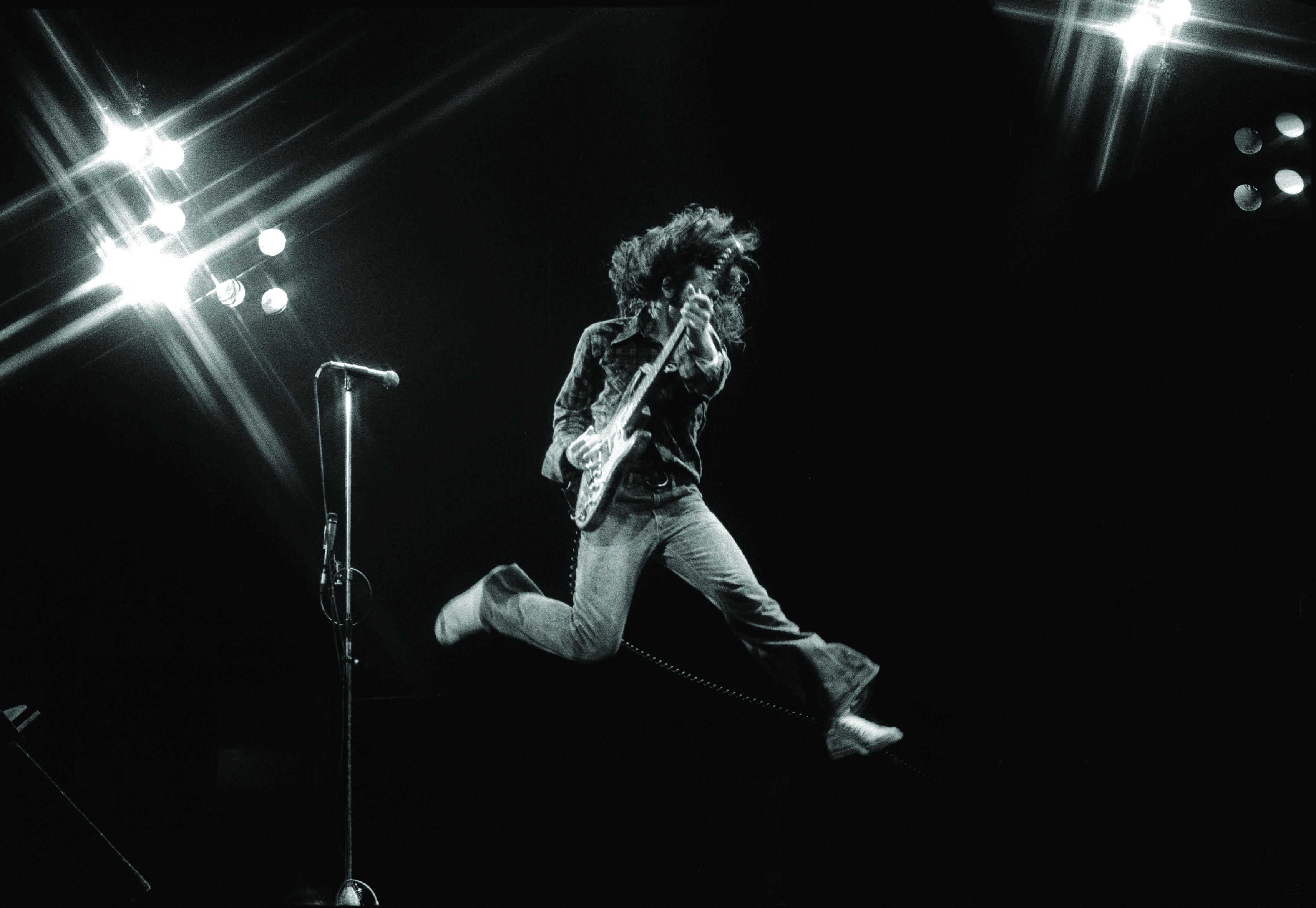

The sheer size and weight of some of the cameras and equipment of the time meant thought was required. ‘When it came to talking and discussing the plans with Donal, Rory was very involved … We decided to shoot on 16 millimetre, which is also quite difficult – you need a lot of light so you can film because it’s very slow negative stock. I said I could probably shoot it with two or three cameras, but you’d end up complaining that all these cameras were in the way … so I’m going to do it on one camera and I’ll tell you where the camera is. I’m going to need a lot of light to see you properly and please don’t wander off to the back of the stage out of light otherwise we’re up shit creek without a paddle.

‘To be fair, I don’t think Donal or Rory were quite sure what I was saying, but as you know Rory was so unbelievably professional that he did get the point and that’s why I got such wonderful shots of him playing, because he knew where the camera was … and I’m standing looking grumpy right behind it … so he always performed for the audience and for the one camera that was there. From a technical point of view, it was very primitive, but in a strange way that gives it its special atmosphere, I think.

‘I think if we did it today … it would have sixteen mini-video cameras whizzing up and down … the silly thing on the crane that shoots across the audience and fast-cutting and all that stuff.

‘I had a long discussion with Bill Wyman about the Stones film by Scorcese, Shine a Light. Bill, of course, is not in it. Bill and I both agreed that the one thing it had was every conceivable facility. Scorcese said it had eighteen cameras. Charlie Watts told Bill there were twenty-five cameras. However many cameras they had, in the end what you miss is the real visceral excitement of going to a Stones concert. So that’s today.’

In early 1975, following the departure of guitarist Mick Taylor, Rory actually had the chance to join the Rolling Stones. Rory’s brother and manager Donal Gallagher received a call from the Rolling Stones management offices wondering if Rory might be interested because Mick Jagger saw a lot in him. The auditions were scheduled for the Hague and Rory travelled on his own, a fact that Donal, many years later, said he regretted. He was put up in a nearby hotel and jammed with the band at a nearby venue. Rory had a tour of Japan fast approaching and with no word from the Stones management packed his bags, leaving a note at the reception desk in the hotel: ‘If you still want me, then I will hear from you.’ Rory departed for Japan.

‘Going back to 1974,’ Tony Palmer continued, ‘the limitations of the technology at our disposal in an odd way gave it the sort of excitement that I’m not sure that if we’d had so called better equipment that it would have helped us.

‘In terms of Belfast I don’t need to remind you of the kinds of problems that were going on at that time. Still, Rory insisted that he wanted to go there. I said “Oh, are you making a political statement.” He laughed and said he wouldn’t know a political statement if he saw it, but in the back of his mind it was very important for him … that he was seen to perform. That was a noble ambition and that’s what we did.

‘Going to Belfast, I pointed out to him, would be somewhat tricky for us, as the BBC Film Unit would insist that I inform them and they would inform Special Branch – and sure enough when we got to Belfast airport we were met by two or three guys. They were terribly nice, plain clothes as it were, jeans and open neck shirts. One of them came up to me and said “I’m from Special Branch. I want you to know we’ll make sure that you’re OK.” When we got to the Ulster Hall we were vaguely expecting trouble and these guys, the Special Branch, were there but in the end there was no trouble, Rory carried the audience along with him. Even he, Rory, was marginally apprehensive that there might be some sort of trouble. All kinds of things were rumoured. Everything went off very smoothly, there was no trouble at all, but it did give the actual concert a slight frisson.

‘I remember when Rory and I talked about it later, when we went down to Cork in fact, that he said “How did you feel in the Ulster Hall?” I said that “I was with you, and I knew that you’d protect me Rory”. He just laughed and thought it was very funny.

‘Rory’s talent was for a long time underestimated, I felt. That was why I wanted to make the film – he was a wonderful musician and I also liked the fact that there was absolutely no bullshit about him and absolute tunnel vision – very professional, minded very much that we reflected that in the film, very private man and wasn’t too keen being filmed coming out of his mum’s house [then in Sydney Park in Cork] but I said unless I put up a caption saying “This is your mother’s house”, nobody’s going to know – that’s the kind of person you are and I don’t want to portray you as something that you are not.

‘For me the most important thing was the music and I convinced him of that, and when he saw the cut of the film he just looked at me and he actually very gently took my wrist and said you kept your promise.

‘I hesitate to say this but I’m just a groupie. I’m in awe of these performers. I can’t play any musical instrument myself so to some extent at that period of my career, even now with classical music, the people I make films about are people I’m in awe of … this is the kind of genius I want to celebrate, I wanted people to know how good these people are … We filmed Hendrix a few years before. I think I was the first ever person to film Hendrix and I’m often asked why did you film Jimi Hendrix – because I’d never heard anybody play the guitar like that before, why did you film Eric Clapton and Cream – because I’d never heard musicians play as well as that before. Lennon and McCartney I liked because they were songwriters of genius. Instrumentally they weren’t that good. The great instrumental soloists such as Rory, these were people whose skill I was just in awe of and when that was coupled with considerable musicianship… I think we filmed every concert on that tour and they were never the same and it was one of my big regrets that the film is only an hour and a bit long … I wished it could have been much longer so you could have seen whole numbers or two versions of the same song and see how much he changes it each night.

‘You never knew quite what he was going to do … that’s what made it very exciting and that’s what the audience responded to too.

‘I said to Rory once, a good while after we made Irish Tour, “I went to a Bob Dylan concert” and he said “How was it?” and I said “He kept reminding me of you.” “How’s that?” he enquired. I said: “He never said anything; he just got on and played”. Rory enjoyed that. Rory got the audience with him because of what he did, what he played and not what he said … it was through the music that Rory wished to speak and it was wonderful music-making.

‘By 1974, I had toured with Cream and with The Who so I was familiar with backstage facilities, which in those days were non existent. Today, a pipsqueak first-time pop outfit wouldn’t tolerate what was being offered back then.

‘People often say to me how did you get such access, but it wasn’t that I got access, there were simply no PR people, no record executives, no bouncers backstage stopping people coming back other than the obvious security. That was the same when we were on tour with Rory. Donal was there, of course, and promoter Jim Aiken but you weren’t aware of swarms of overfed, overpaid nonentities PR people or even more dreadful moronic half-witted record executives … they just weren’t there.

‘I don’t remember anyone wearing a backstage pass during Rory’s tour, I really don’t. But it wasn’t as if it was open house; Donal, in particular, was careful in not letting the swarms come backstage. I don’t think Rory would have worried. He would have worried beforehand because that’s a period of intense concentration and preparing himself really. Rory was very disciplined: I admired that about him, I learnt that very early on. I’d known that from other very great musicians I’d been backstage with that the worst thing you can do before a concert is talk to them: they don’t want to talk, they’re focused on what they are about to do.’

Rory Gallagher: His Life and Times by Marcus Connaughton is published by The Collins Press and priced €19.99. It is available in bookshops and online from collinspress.ie.

Published on 25 October 2012