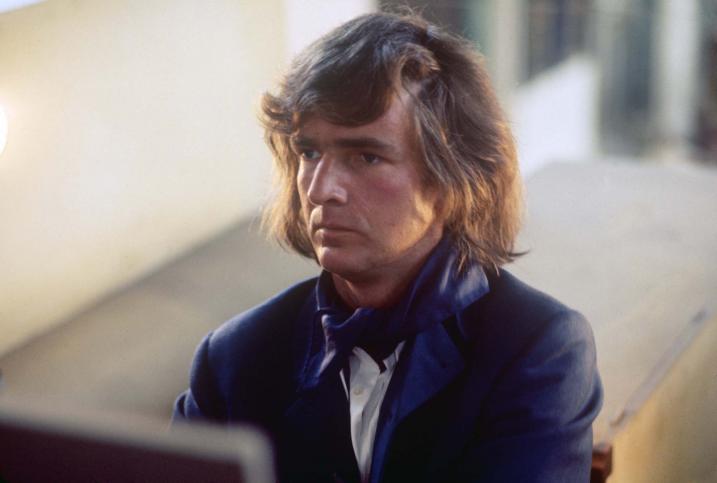

A young John Tavener

John Tavener Remembered

The death of English composer Sir John Tavener at the age of sixty-nine this week prompted tributes from around the world, including many claims that the description of his music as ‘holy minimalist’ by critics is ill-suited. Speaking to NPR Susan Hellauer of the group Anonymous 4 said that, despite its aparrent simplicity, the music is very difficult to perform. ‘It actually floats. It appears out of nowhere, and then it floats back into nowhere,’ she said. ‘It doesn’t have that kind of Western structure of themes and developments. It just is, and then it’s gone. And very well-crafted. His music is not easy to sing. It sounds simple, in a way. There’s not fireworks-type technical demands, but the demands are in sustaining a line, sometimes very long notes, holding the line up for long periods of time, in a very quiet way.’

Tavener, who suffered a series of heart attacks in 2007, converted to the Russian Orthodox church in 1977, which is said to have influenced much of his composition. Writing in the Guardian, composer Nico Muhly said that to study Tavener’s music is to ‘immerse oneself in the subtle vocabulary of stillness and change’ adding that the English composer has had a significant effect on a younger generation of composers.

‘There is much to be learned compositionally from careful study of his patience and surprise revelations,’ wrote Muhly, ‘but I am more interested in how singing his music has enabled a generation of musicians to really enjoy stillness and circular structures. Much of the modern Anglican choral tradition is built on glorious, directional phrases that coddle the text. Tavener’s music usually insists on simpler textures: a drone, and an economy of one or two notes per syllable (or, in more extreme examples, one syllable stretched over many, many, many notes). To sing this music is to learn how to resist romantic phrase-shaping, and to make the beauty in expression more to do with what is withheld than with what is presented.’

Other tributes came from Prince Charles (Tavener’s Song for Athene was performed at the funeral of Princess Diana in 1997) and from the composer Sir Peter Maxwell Davies, who said that Tavener’s death was ‘a great loss to the world of spiritual music’.

James Rushton, managing director of Chester Music, Tavener’s publisher, said that the composer’s work was ‘always identifiably his’ and said that his output was ‘one of the most significant contributions to classical music in our times’.

Cellist Stephen Isserlis told the BBC that Tavener had a unique voice within a ‘fractured’ classical music world. ‘He wasn’t writing to be popular,’ said Isserlis. ‘He was writing the music he had to write.’