No Anxiety

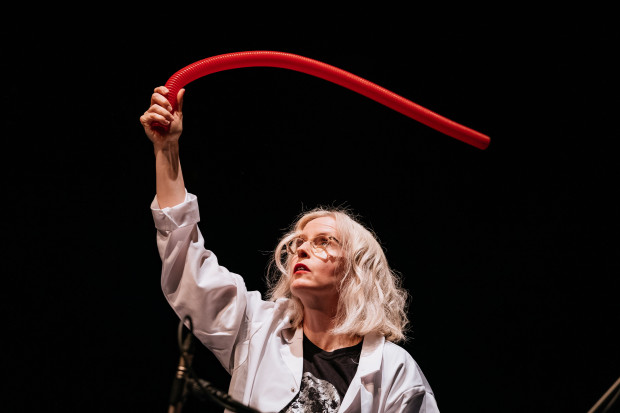

Photographs of Seán Clancy by Alan Moore

Seán Clancy studied composition in Dublin with Kevin O’Connell, in London with Rob Keeley and George Benjamin, and in Paris with Phillipe Leroux. Since 2009 Clancy has been working towards a PhD in composition at the Birmingham Conservatoire with Howard Skempton and Joe Cutler.

Clancy has held the position of Birmingham Contemporary Music Group/Sound and Music Apprentice Composer in Residence since January 2011, a position which has involved being mentored by Pulitzer Prize winning composer David Lang, as well as being able to work closely with the musicians of the BCMG, particularly in developing a large ensemble piece to be premiered at the end of the residency.

In December 2011, Clancy, along with another Dubliner, Enda Bates, was awarded with a RTÉ Lyric FM and Irish Music Rights Organisation Mentored Composition Bursary. The bursary will give Clancy the opportunity to gain experience in working with and writing for the full RTÉ National Symphony Orchestra, under the guidance of the current RTÉ Lyric FM Composer in Residence, Linda Buckley. Clancy’s orchestral piece will eventually be workshopped and recorded by the RTÉ NSO.

Clancy’s music has developed fluently out of an interesting but somewhat anachronistic engagement with modernistic strict atonality and hieraticism of pulse, through lessons about harmony-timbre drawn from spectral music and a passionate recuperation of forms and gestures from popular music, into the Andriessen and Skempton-influenced compositional style of today. That compositional style might be described in broadly post-minimalist terms, but the category is too limiting for Clancy’s protean and still-evolving work. Listen to a wide-range of Clancy’s music here.

Clancy’s ensemble piece for BCMG under Clement Power and with soprano Susan Narucki, Findetotenlieder, is inspired by LCD Soundsystem’s ‘Someone Great’ and Mexican artist Gabriel Orozco’s Obit, and will receive its premiere in CBSO Centre on 3 February in a programme with music by Judith Weir, Gerard Grisey and Gerald Barry.

Ahead of the premiere, I spoke to Clancy about some of his formative influences, about the processes of the residency, and more generally about his status as an Irish composer currently making his career largely abroad.

Can you describe the moment, or series of moments, when you decided you wanted a life in music?

It’s incredibly difficult to answer this question as all of the music I write now deals with these formative influences and I think about these things quite extensively. However, I suppose from the age of about twelve or thirteen when I started playing in grunge bands I knew I wanted a life as a musician. When I decided I wanted to study music in college aged around sixteen, I began to take piano lessons which opened my eyes to a whole other range of music.

I can pinpoint two exact moments when I knew I wanted to be a composer (a very specific kind of musician!).

The first was when I was around sixteen. I bought an ECM recording of The Seasons by John Cage solely because I liked the beautiful cover. On the CD there was a recording of 74. I remember coming home from town and listening to the piece on my bed whilst reading the liner notes. I was completely overwhelmed by the sound of the piece, but even more so when I read about how it was put together or composed. From that moment on, I knew I wanted to write music like this.

The second moment came when was when I was about 17. I went to a RTÉ NSO Horizons concert featuring Gerald Barry. In the concert Gerald had programmed a piece called Lento by Howard Skempton. I was so completely and utterly taken aback by the piece, the players’ engagement with it and the audience’s attention to it, that if I had ever any doubts about what I was going to do with my life (I had at this stage been briefly seduced by a career in photography) it was now completely obvious. It’s kind of nice to think that now things have come full circle as I’m finishing my PhD in composition with Howard, who first inspired me to become a composer.

I think most things I encounter in my life serve as an inspiration for my compositions. For the past three years, however, I would suggest that my principle inspirators have been first and foremost popular and underground music artists, and visual artists, particularly Martin Creed, Gabriel Orozco, Whelm de Kooning and Philip Guston. In terms of composers, I tend to be solely inspired by composers whom I know on a personal level, notably David Lang, Howard Skempton, Joe Cutler, Gerald Barry, Louis Andriessen, Donnacha Dennehy, Andrew Hamilton, Ed Bennett and Philippe Leroux. Then of course there’s Feldman, who, as everyone should know, is endless.

How have you felt your work growing as you’ve aged?

As I’ve gotten older I’ve become more confident in my musical ideas. I’m less concerned about what others think of my music and as a result I’m not that interested in pursuing what other composers may see as musical progress (I’d suggest that this is a hangover from modernism). This has resulted in my musical language becoming less complex (what Cardew might have called radical simplification), and I’m now trying to re-connect with all of the music that I love in some way, particularly my formative musical experiences, and not just contemporary classical composition. I’d suggest the main ‘development’ in my music is that I’m no longer concerned with musical invention, but artistic intervention.

Does your music have any global organising goals or objectives, whether these be musical, literary, philosophical or trivial, personal, affective, imagined or otherwise?

I’d suggest that it varies from piece to piece. Each specific piece will have its own specific objective, be it musical, personal, philosophical, etc. I try to embed, within the piece, a reason for one to listen to it as opposed to something else. There are, however, certain things which continuously crop up in my music. The first is artistic intervention; each piece I’ve written over the past three years has in some way dealt with pre-existing music or art. Other issues that constantly find their way into my music are death and voyeurism.

What kind of things has the BCMG/SAM apprentice composer in residence position enabled you to do?

Basically, I was given complete access to the workings of the organisation both on an artistic and an administrative level. I’d suggest that the main benefits for me were attending rehearsals, meeting other composers, conductors and musicians, getting to work with David Lang, getting to go to New York, being involved with the education and outreach programmes, seeing how programmes were put together, getting to work with world class musicians and soloists, being taken seriously as a composer, the exposure of being associated with such a group, and, last but certainly not least, receiving two commissions of which I’m very proud.

Can you discuss the main ensemble piece you’ve written as part of the residency? What inspired the piece, and what have been the effects of committing the piece to dialogue with performers and audiences?

The piece utilises two sets of taken material. The first is Gabriel Orozco’s Obit, which I suppose is the driving force behind the piece; the second is LCD Soundsystem’s ‘Someone Great’. The piece is essentially an artistic intervention on these two objects. I had quite a long gestation/composition period with it (beginning in April 2011 and finishing in December 2011), so I had a lot of time to think about it carefully, make revisions, tweak, edit, etc. It’s a very exposed piece, there’s no margin of error, no safety net, lots of space and intricate (but uncomplicated) writing.

In terms of the dialogue with performers, it was very important that each member of the ensemble was aware of what they were doing to the singer and what she was doing to them; they are mutually aware of each other, there is not a straightforward soloist/support dialogue but both are as integral to the musical material as each other and the piece is riddled with musical signifiers to demonstrate this. In terms of the dialogue with the audience, I’d not like to suggest a reading of the piece, but for me it certainly makes one think of death and our attitudes towards it in the twenty-first century, as manifested through the media.

You’ve also recently been awarded a bursary to compose an orchestral score for the RTÉ NSO. What is your reaction to the award, and how do you feel looking ahead to the composition of the score?

I’m absolutely thrilled about receiving this award. Ever since I was a teenager going to NSO concerts on Friday evenings I always wanted to write for them. It’s a little daunting looking ahead to the score. I’ve written two orchestral pieces before but neither were performed so I don’t know if they would actually work in reality or not! Knowing that this piece will definitely be performed in the coming months raises the stakes a little and makes one take it a lot more seriously.

I’ve a fair idea what I want to do with it. I often find that orchestral music is very polished. Every change in section or material is really well dovetailed and disguised, and I find that highlights an anxiety on the composer’s part. This anxiety of change just doesn’t exist in rock music. I’m particularly interested in a certain Faith No More song at the moment on which I’ll probably intervene, because structurally it’s very interesting and contains no anxiety whatsoever. Either way, I’m interested in trying to make the orchestra sound a little less like an orchestra, but not in a ‘new musicky’ kind of way. How successful I am at this remains to be seen, but I relish the challenge.

Finally, as an Irish composer living abroad, how do you think your ethnic identity (if you accept one) affects your music, and secondly, what do you think more generally about the situation of the Irish composer — émigré or not — at the start of 2012?

I’d accept my ethnic identity because up until the age of about twenty all of my experiences were intrinsically Irish, and these have formulated the way I think and act, etc. In Ireland we don’t have the tradition of classical music that exists in other places (Britain, France, Germany, Italy, etc.), so we don’t necessarily feel as if a torch has been passed to us in some way. I think this leaves us open to acting like magpies and taking what we find interesting from different musical traditions, whatever they may be. Living abroad one sees these traditions in operation because one is removed from them, one can never get into them, so you just sit on the outside and take notes, which obviously affects the way you write and the way one’s music is received. I think this can only be a positive thing. One becomes more concerned about the music rather than the things that surround the music.

I think Irish music is in an incredibly healthy position at the moment. Composers like Gerald Barry, Kevin Volans, Donnacha Dennehy and Ian Wilson are internationally known and are given as much credence as anyone else you’d care to imagine. Coupled with this, there’s the likes of slightly younger composers like Jennifer Walshe, Andrew Hamilton, Ed Bennett, Dave Fennessy, Linda Buckley and Judith Ring who are also household names across Europe and beyond. Then there’s my generation, many of whom are winning or at least being nominated for international prizes as well as doing their own thing.

In addition to this, Irish composers have fervent advocates for their music in the Crash Ensemble, Concorde, RTÉ NSO, Fidelio Trio, Ergodos and organisations like the Contemporary Music Centre and the Association of Irish Composers. We may not have as much money or as many compositional opportunities as other countries but we’ve certainly got a lot to be proud of and a lot to look forward to in 2012. I genuinely believe that much of the best music being written at the moment is being written by Irish composers whether at home or abroad. I will, however, probably be crucified for making such a sweeping nationalistic generalisation!

Published on 26 January 2012

Stephen Graham is a lecturer in music at Goldsmiths, University of London. He blogs at www.robotsdancingalone.wordpress.com.