Live Reviews: RTÉ Living Music Festival: 25th October concert

The Living Music Festival, 25th October

Mahony Hall, The Helix

The RTÉ Concert Orchestra

Friedrich Goldmann, conductor

Maurizio Barbetti, viola

Stockhausen — Formel (1951)

Berio — Chemins II (1967)

Hamilton — MAP (2002)

Berio — Requies (1983-4)

Stravinsky — Agon (1957)

The first thing to say is that it was good to hear every instrument so clearly in this new concert venue. A few days prior to this festival I stuck my head in the door of the upstairs balcony of this hall. Below me workmen were onstage with a transistor radio on the floor, tuned in to some current affairs programme. I could hear every word coming from that radio, even though my position was far away.

This good acoustic served the Stockhausen well from the very beginning. Sparsely orchestrated and composed when he was only 23 you could hear clearly the music move though its twelve segments, orchestrated differently each time. The piece progresses at its undramatic pace and just as you’re beginning to think he’s overdoing the variations – it ends, leaving behind a feeling of retrospective validation.

In Berio’s Chemins II (composed in 1967, two years after his unquestionable masterpiece Laborintus II), the viola part evolved out of Berio’s previous work for solo viola, Sequenza VI, where the viola furiously attempted to sustain a four-part harmonic discourse (only two strings playable at any one time). This time keyboard and pitched percussion play the completed harmonies of Sequenza VI with the ensemble adding more complex material as Maurizio Barbetti reproduces chunks of Sequenza VI under it all. Again a full clear sound, but for this reviewer the ideas contained in the piece did not communicate fully to produce a musically engaging experience.

The new commission from the very up-and-coming Irish composer Andrew Hamilton came with a good deal of anticipation as his work that won the Mostly Modern Young Composer’s Competition a few years ago made an extremely good impression. Hamilton has since adopted a minimalist approach and doesn’t rate that earlier work now.

MAP sets up a faltering unsteady rhythmic language full of tonal tuned percussion, giving the impression of some music box owned by a neurotic – a ‘weird machine of joy’ as the composer describes it. So far so good. Hamilton, somewhat like Stockhausen, says in the programme note that he: ‘tried to write a piece in which different versions of the same pattern are always colliding’. This was not evident. What communicated instead was a language with many possibilities in which the collisions cancelled each other out giving the feeling of not getting anywhere. There is also a danger in working inside a particular genre that has been so exhaustively dredged, that pieces will begin to sound similar to each other, unless the composer’s stamp is a strong one. I didn’t feel as strong a stamp here as in his earlier work.

Berio’s Requies (in memory of his ex-wife Cathy Berberian) is obviously a deeply-felt piece in which an ‘ideal melody’ is stated with constant timbral changes. It left no lasting impression. It is difficult to know what the problem was here, as I hadn’t heard the work previously. Is it the performance, is it the conductor, is it me?

Stravinsky’s Agon received its first ever Irish performance, which is hard to believe, but true. This is a work I first heard 30 years ago on BBC Radio 3’s ‘Music in our Time’, a programme which I listened to and taped every week, and from which I and other composers educated ourselves (Berio’s astonishing Sinfonia was first heard here too). Agon is ballet music from 1957 in 17 movements, composed when he was 75. He daringly allowed a whiff of serialism into this piece. His orchestration is still spiced with totally original ideas (the double basses playing harmonics with the flutes). I believe that Stravinsky indulged himself in academic excercise a little too much in some movements (maybe you have to see the ballet, in which the number of dancers for each movement is strictly specified), but neverthless hearing this piece in the flesh, and performed so well, was a great end to an evening’s music, the kind of which we must dare to imagine will become more frequent.

Published on 1 November 2002

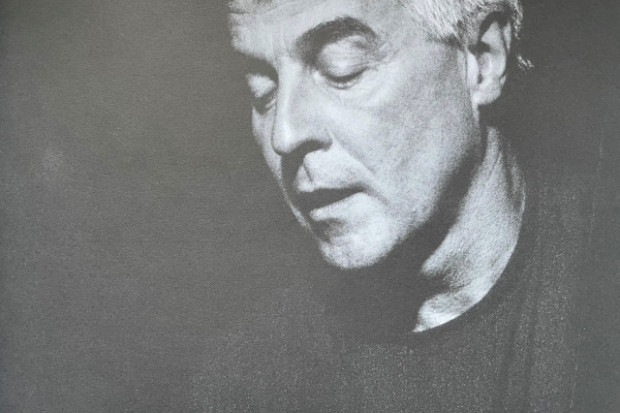

Roger Doyle is a Dublin-based Irish composer working in electronic music.