The Bitter Tears of Petra Von Kant

As a listener who is also a composer, attempting to absorb and appraise a substantial new piece is a process that often calls for a near-unattainable degree of compartmentalisation. Sometimes ones first reactions take the form of creative interventions: ‘why do it like that when you could have done this?’ If many such questions or objections keep popping into ones head, the concept of balanced and fair appraisal may go out the window, as one starts to re-write or re-plan the piece.

With Gerald Barry’s The Bitter Tears of Petra Von Kant (27th May, NCH) my experience was certainly clouded by a strong desire for him to write, at times, differently. I longed for a few slow notes, some major change of pace, some relaxation. It was not to be. This was a relentless assault on the ears, of highly charged energetic musical and dramatic tension, lasting almost two hours in total.

The structure was quite extraordinary, and I am not just throwing words about. What I mean is that at any given moment the listener would be enjoying a short passage that made perfect musical sense – albeit usually charged up in some way – then this would be summarily left behind as a completely different segment would cut across or replace this thought. The local language within such passages was always logical, sometimes mockingly predictable, while the relationship of each segment to the next appeared arbitrary – one simply could not hear why the material kept changing radically. Such a confrontation between modes of discourse at two different but adjacent levels is certainly a challenge to the notion of structure itself – though this is clearly not some aesthetic accident on the part of the composer. If Barry is called a musical maverick, it is for reasons such as these.

These primary qualities of the writing remained constant for five acts. If one were looking for a visual equivalent, imagine an abstract collage made up of fragments of photographs from magazines. The fragments that were assembled thus were not endless in number, so of course one frequently recognised material from earlier; this gave an impression of coherence at the next level. By act three of five (after the interval) one began to settle in to the right frame of mind! The dangers of such a method seemed to be recognised (though perhaps not removed) by the composer: he landmarked certain formal points such as the ends of acts and the dramatic turning points (such as Karin’s revelation of inter-parental murder and Petra’s declaration of love) by allowing longer and more internally developed stretches of continuous textures. Certain very simple motivic devices also framed the acts.

Pure music

The piece is an opera, and this presentation was only in the form of a concert. So, naturally, most of the audience were left wishing they could see a full staging. There were several remarkable aspects to this opera that attest to Barry’s independent way of working: firstly, for a libretto he used a translation of a play by Rainer Werner Fassbinder, without any reduction; secondly the opera is possibly unique for having only female characters and voices – five singers plus a sixth female character with no text. The lack of textual reduction goes in hand with Barry’s usual text-setting approach: avoidance of melisma and rapid-fire delivery (leaving no time to employ any vibrato, incidentally). But text such as ‘Marlene, make some coffee. Or would you prefer tea?’ ‘Coffee’s just fine.’ ‘Have you had breakfast?’ calls out for pruning.

The music and text interacted in varying ways according to the layout of dialogue. Since the music was independently committed to frequent changes of texture and material at roughly a constant rate, it had the effect of cutting up textual continuity wherever one character had a long monologue (such as the beginning of Act 1), but of unifying text where characters were in rapid dialogue (as at the start of Act 3). Dramatically this may seem perverse, since the music will mollify character conflict (in Act 3) yet disjoin character exposition (in Act 1).

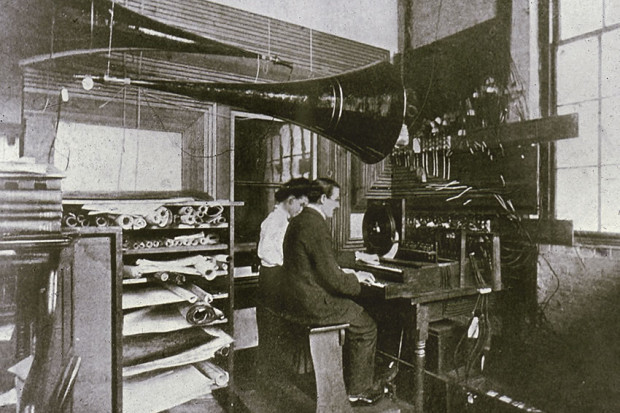

The effect of this was refreshing rather than frustrating, and it moves the piece further into the realm of pure music. Essentially this seems to be what Barry is doing: this is a piece of music which incorporates text (and will incorporate drama when staged by the English National Opera, the co-commissioners along with RTÉ) – it is thus closer in concept to an older, pre-Wagner view of opera than at first appears. The text did not impinge whatsoever upon small or middle-scale musical structure, but the storyline ultimately organised the music’s formal scheme. Through Acts 1 and 2 the lines given to the singers belonged in the music, but during Act 3 an increasing tendency to sing for up to eight syllables on one note made it sound as though the instruments and the vocal lines were peeling apart. Acts 4 and 5 returned to the previous state. But the perception of the piece as pure music is hard to avoid in a pure concert presentation: the effect of the piece would have been utterly transformed even had the various moments where Petra puts on records (by The Walker Brothers and the Platters) been represented through the P.A.

A milestone

The story seemed to exist to insult the standard middle-class mind-set. The chief protagonist Petra is a drunk divorcee who is experimenting with her sexuality by making predatory advances and deluded love declarations towards the less educated/successful Karin. She also gets around to using and abusing her assistant, her mother, her daughter and her friend. It is hinted that her assistant whom she treats as a servant, is actually the one behind Petra’s success as a fashion designer. It is unlikely that the audience is going to have the slightest sympathy for anything that might befall this monstrous egotist, though one is offered the notion that she is all the time merely in pursuit of love (from all of the others) that is not being returned. By throwing in all of the above and references to inter-parental murder and a ‘big black man with a big black cock’, it is as if a checklist of offence for middle-class opera audiences is in operation. As a play this could be blackly comical, but with the stricture of music’s timing it is impossible to really create comic timing, and it takes some effort not to see the story as merely a contrived attempt to be un-pc, ironic and sensationalist. Either way, having a hollow drama is another strategy for moving music to the centre of things. The plotline, unlike the musical structure, is strictly linear. This is yet another way in which the music remains independent from textual structure.

Returning to the music itself, this opera presents some of Barry’s best orchestral writing. The instrumental colouring was well-defined but never obvious, which helps when the vocal resources are limited, not only to sopranos and contraltos but also to linear writing, i.e. there were no duets, etc. Rayanne Dupuis put in a staggering effort to sing the part of Petra von Kant, who is present and busy throughout the opera. Mary Plazas, as her lover Karin, and Stephanie Marshall as Sidonie also had much to do and did it extremely well, with colour and energy. Sylvia O’Brien, as Gabi, Petra’s daughter, was generally up to the same high standard. The least busy part, Valerie (Petra’s mother), was sung by Deirdre Cooling-Nolan, who produced the most emotionally engaged singing of the evening.

It is frustrating that what this piece clearly deserves – and actually needs if it is to be received properly – is a staging in Ireland, yet the staging will be realised in London by English National Opera. New Irish opera that uses a full orchestra has no real ‘home’ among the existing production companies in Ireland. This is a sad situation especially as it affects this major work which is a milestone not only in Gerald Barry’s oeuvre but in the history of opera in Ireland.

Published on 1 July 2005

John McLachlan is a composer and member of Aosdána. www.johnmclachlan.org