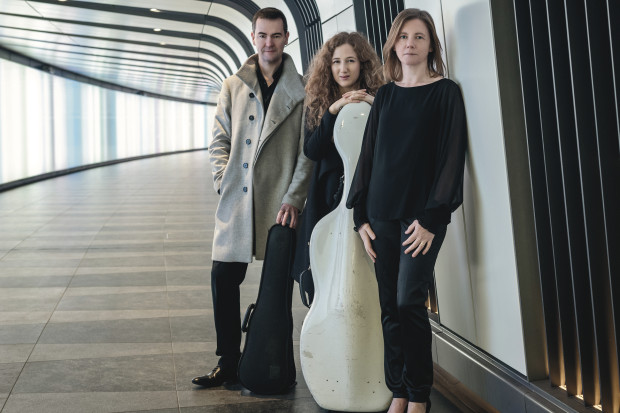

Brian Boydell composing, c. 1947 (Photo: D.O. Michelson, courtesy of the board of Trinity College Dublin)

The Composer as Raconteur

‘I was in the most unusual state this afternoon of being actually bored’ notes Brian Boydell one April evening in 1950. When one considers the range of activities in which Boydell involved himself one understands how novel the feeling must have been. While he ultimately positioned himself as a composer, he managed to engage in almost every aspect of music-making in Ireland in the post-war years, performing and teaching as oboist and singer, conducting the Dublin Orchestral Players (DOP) and other groups, forming and directing the Dowland Consort for the performance of early vocal music, writing and broadcasting talks on music, giving gramophone recitals and adjudicating at competitions around the country, before eventually becoming professor of music at Trinity College Dublin where he completely revamped the curriculum. What spare time could be found was spent on gardening, motoring and fishing. When one adds in his involvement with the Musical Association of Ireland and the Arts Council and his musicological writing it is clear that any historical account of music in Ireland during this period would need to grapple with his legacy, as clearly his influence was significant.

The first and slightly longer part of Rebellious Ferment is taken up by a memoir written by Boydell in the 1990s originally titled ‘The Roaring Forties’, while the second part of the book gives extracts from his diary from the first half of 1950. In particular, the publication of a memoir would on the face of it seem to be good news for anyone interested in musical life in twentieth-century Ireland. On reading it, however, the real surprise is how someone at the centre of so many aspects of cultural life could have so little of substance to say.

The best memoirs are those written by people with very good memories (whether aided by diaries or not), who have good powers of observation and are able to convey a clear impression of events and people. The preface by the editor, Boydell’s son Barra, describes the memoir as ‘a primary source for this intriguing period of Irish cultural history’ while Boydell himself states that his aim is ‘to record impressions of events and the personalities (other than myself) involved in them.’ However, one doesn’t get much sense of Boydell taking time to observe anyone else with any depth. Despite his professed dislike of autobiography, inherited from his father who described it as ‘an act of indecent self-advertisement’, one gets the sense that the memoir is very much about the heroic Boydell in a series of improbable positions surrounded by a range of caricatures. In fairness, the composer does warn in a preface that raconteurs are always tempted ‘to add little bits here and there when repeating the story over the years’ until the author can no longer tell what was real and what was invented and that the details may be ‘inadvertent flights of the imagination’. However, this does not quite prepare the reader for what is a series of tall tales, each one told so often that it has acquired truly ludicrous embellishments. Doubtless they were all most amusing when told in person with ebullience and accompanied by large quantities of alcohol. However, on the page they begin to pall as we drift from one over-embroidered incident to the next

Encounters

On the one hand, there are the various adventures of the intrepid Boydell who always survives unscathed no matter what he encounters. During the war, running his car on producer gas he inhaled ‘vast quantities’ of carbon monoxide but only got a severe headache. On another occasion, having accidentally cut a hole in the bottom of their currach, Boydell and friends just make it back to shore just before it fills with water, a scenario further complicated by the presence in the boat of a live six-foot conger eel. Jumping into a river in the attempt to land a giant salmon he finds himself swept fully clothed into a pool where he is ‘out of my depth with my mouth just above the surface’. Despite this inconvenience and the weight of his soaked clothes, which make it almost impossible for him to stand, he manages to plough on for half a mile, naturally wandering through several more deep pools but just as he is finally about to drown he manages to make it ashore, like an Irish James Bond. And yes, on another occasion he is even mistaken for a dangerous spy, allegedly.

Other stories require the assistance of simple-minded locals. Engaging with a friend in the intellectual pursuit of loosening large boulders and sending them over the edge of cliffs without checking to see if there is anyone in their path, they terrorise a shepherd who naturally does not call out to make them aware of his presence. Instead he cowers against the hillside for hours, only surfacing for comic effect in the midst of Boydell’s dinner preparations. The population of Achill multiplies sharply after a crate of condoms is washed ashore as the islanders don’t realise they have been damaged by their sea voyage. Even Boydell’s friends bear the brunt of his wild fancies. He ‘distinctly remembers’ Nigel Heseltine throwing Irish Times critic Charles Acton out of a first-story window (doubtless the wishful fantasy of many composers and performers) but admits in a footnote that neither person has the slightest recollection of anything remotely like this happening. Introducing a portrait of another friend, Ralph Cusack, he begins, ‘Bearing in mind my anxiety not to paint a distorted picture, I cannot resist describing just a few of the bizarre events which are quite unforgettable.’ We brace ourselves for the worst. Another boozy tale of spies and mayhem begins with the prefatory words ‘One occasion however does stand out in my mind. The befogged details may well be quite inaccurate.’ But such issues do not halt the shaggy stories. Staging performances of Haydn’s ‘Farewell’ Symphony with the DOP in which the players played by candlelight and put out their candles as each one left the stage, Boydell states that in the Dublin concert and in a later performance in Cork ‘there were alarming accidents as members fell off the stage in the darkness, injuring either themselves or their instruments.’ Sadly the diary in the second half of the book documents the 1950 Dublin performance but fails to mention any fatalities among musicians or instruments.

Brian Boydell conducting the final rehearsal for the Dublin Orchestral Players’ tenth anniversary concert on 16 June 1949 at the Metropolitan Hall, Lower Abbey Street, with the string section playing Sibelius’ Romance in C for Strings, Op. 42. (Photo courtesy of the Irish Times)

Commentary

If you are looking for insights into the artistic milieu in which Boydell operated then you are going to be disappointed as the memoir determinedly avoids anything like serious commentary. Of his involvement with the White Stag Group he says that all he can provide the reader with is ‘the colourful background.’ The foundation of the Music Association of Ireland (MAI) which was to be the driving force behind so much of Ireland’s musical activity at first looks like it may receive some attention. Boydell states he is about to give us ‘a historically correct account, thus differing from some previous reminiscences’, but after reprinting their original position statement he quickly diverts away to his favourite anecdotes. The gradual expansion of the Radio Éireann Symphony Orchestra, an event of crucial significance not least for Irish composers, is merely the excuse for tales of the odd behaviour and amusing ways of those funny foreigners who were employed by RÉ. Thorough hatchet-jobs on two of the conductors of the orchestra, Milan Horvat and Tibor Paul, follow. A brief mention of Stravinsky’s visit to Dublin tells us nothing regarding the performances he and his assistant Robert Craft conducted; instead it is merely the cue for another well-worn anecdote about Stravinsky letting on he knew who the distinguished composer Boydell was. The memoir ends with Shostakovich’s visit to Dublin and Boydell’s naive surprise that the composer did not engage in a diatribe against the Soviet Union while in conversation with Boydell via an interpreter he had never met before.

Igor Stravinsky with (left to right) Geraldine O’Grady (leader, Radio Éireann Symphony Orchestra), Novemo Salvatori (principal trombone, RÉSO), Brian Boydell and conductor Tibor Paul, June 1963. (Photo courtesy of Independent News and Media and the Irish Independent, and the board of Trinity College Dublin)

Boydell insists in the preface that everything is at the very least based on fact but with so much that is clearly false one finds oneself wondering if anything in the book is remotely true. The three to four pages devoted to the tenure of Milan Horvat are a good example of the problem. It begins with a ludicrous description of how he would sweat so much while conducting Irish compositions (but it seems not other works) that ‘the ink of the notes ran and merged into a hazy blotch’, something which isn’t actually supported by the surviving manuscripts. We are then told that in the dark anti-Communist, Catholic, and, by implication, pro-Fascist Ireland of the 1950s, the appointment of Horvat (who was from Yugoslavia) led to the minister in charge being ‘bombarded’ by deputies from around the country. Recent research has demonstrated that there was in fact no objection made to the minister. We are then told one of his ‘funny foreigner’ stories in which the trombonist, an Italian, decided to sabotage a performance Horvat was conducting of Ravel’s Bolero at the Gaiety during the Cold War confrontation between Italy and Yugoslavia known as the Trieste crisis. However, it seems Horvat did not conduct Ravel’s Bolero in Dublin at all, and certainly not in a Gaiety concert. Stories of Horvat’s recording of Irish composers’ work on two LPs are primarily limited to telling us that the American producer was far more acute and musical than Horvat, though it has to be noted that Horvat managed to go on to have a substantial international career after his spell in Dublin. Finally we are given an unpleasant story to demonstrate how parsimonious Horvat was, but here Boydell adds as an afterthought that he wasn’t present when the alleged incident occurred and that someone who was there had no recollection of anything like this happening. Faced with such a range of malicious gossip and false information one can’t help wondering what lay behind such smouldering resentment, but it also demonstrates how great a task it would be to sort out truth from fiction if a proper academically annotated edition was to be prepared.

There is little commentary on music in the memoir. At one point, he notes, ‘I believe we did indeed put on, and get away with, some pretty appalling performances in Dublin during the forties, as well as experiencing much excellence’. However, he seems to have no interest in documenting the excellence. In both the memoir and the diary he is quite frank about the sometimes deplorable level of performance attained by the DOP, but clearly he believed that in the 1940s and 50s it was better to do something badly than not do it at all. In this he was undoubtedly right but surprisingly the third chapter of the memoir concludes with a passage in which he seems to deplore the raising of performance standards and the increased professionalism of music-making in Dublin. He argues that this decreases the ‘fun’ aspect of music and somehow believes that as people get used to higher standards their enjoyment level decreases. Perhaps this is merely the sentimental nostalgia of someone who feels that the sort of concerts he put on with the DOP would no longer have a place in this new world or perhaps he felt marginalised in later life when he was no longer such a dominant force on the music scene.

Diary

While the memoir may perhaps provide entertainment for people with a strong sense of the ridiculous, the diary which forms the second half of the volume provides moments of genuine interest. As always with diaries, one wonders whether it was kept solely for himself or with posterity in mind (though it seems from the editor’s preface that its survival was accidental) and certainly some entries have a performative streak as he tries out various bon mots. As against this there are moments of the sort of personal reflection that is completely absent from the memoir. He worries about his ‘lack of knowledge on so many important things – e.g. the Beethoven sonatas, Wolf songs, Bach’s 48’. He feels under pressure to always have a vocal opinion about a performance at any concert he attends and as a result finds it difficult to judge both a work and its performance, as concentrating on one means he cannot focus on the other. He spends much time weighing up possible conducting jobs in Ireland and Britain while bemoaning the fact that the RÉSO fails to take him seriously as a conductor. His frustrations with teaching voice students of varying abilities are documented and he improves his own singing before a performance with an interesting combination of sherry and Benzedrine.

The composition of The Buried Moon and the premiere of his First Quartet are covered in some detail. Parallel to this we see his excitement as he gradually discovers a wide range of music via recordings and radio broadcasts. His attempts to record pieces from the radio contrast strongly with the easy access to music we have today and when the BBC moves to a different wavelength giving better quality reception he eagerly anticipates the ‘possibilities this opens up!’ Hindemith, Kodály and Florent Schmitt and a programme on African music are among the things that arouse his interest. On the other hand, listening to Berg’s tonal Piano Sonata, Op. 1, he feels that ‘Berg was striving after noises’ while Alois Hába’s music ‘sounds very sick – like an athlete whose muscles have collapsed.’ His highest praise goes to the second violin concertos of Prokofiev and Bartók, but most of all to Bloch’s Second Quartet which he declares ‘one of the masterpieces of our time.’ We get an interesting picture of his work for the DOP. Programmes are chosen based around the instruments available, though sometimes pieces are rearranged for the orchestra, with Boydell at one point substituting clarinets for trumpets. We also hear about the tribulations of dealing with copyists in those pre-computer days to obtain parts for performances of compositions.

Despite the genial image created by late interviews, he clearly was not an easy person to work with and he suffered the pangs and self-inflicted problems of one who felt he was the only intelligent person in Dublin. Before taking a solo part in a performance of Mendelssohn’s Elijah he notes, ‘I shouldn’t really sing in public at all, since I haven’t time to practise regularly… but I can’t bear letting unmusical idiots take my place.’ Doing a live broadcast about Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony illustrated with examples from 78s, he moans ‘It is incredible that I am expected to read my script, and work the records at the same time: though in actual fact there is no one available whom I could trust to do the records properly.’ Rehearsing the DOP he notes ‘the second violins were very stupid and exasperating, calling for a good deal of sarcasm and mild fury.’ In the final substantial entry in the diary he ruefully tells himself he shouldn’t get worked up about things after having a row on the phone with Charles Acton. However, by the end of the same day he was so incensed that a broadcast performance of Bach’s B Minor Mass, which he wasn’t enjoying anyway, was faded out some seconds before the end of the work that ‘trembling with rage’ he rang RÉ and ‘told Miss O’Brien what I thought of her’. When someone at a public talk has the temerity to praise American jazz, Boydell notes with satisfaction that he ‘tore him to shreds.’ It doesn’t stop him listening to jazz on one of his gramophone evenings with friends a month later.

Negative views

Considering how influential on Irish musicologists Boydell’s negative views of Irish nationalism and traditional music have been it is interesting to trace his attitude towards Ireland and the Irish in the two parts of the book. The natives (outside of his small inner circle of friends) don’t play much of a role in the memoir and in the main are represented by romantic islanders (the people on Achill display ‘an inspiring simplicity in their way of life’ until this was eroded by their unpalatable desire to seek ‘easy riches as labourers’ in England) and half-wit policemen. In the diary his views are consistently negative. In most interviews and in this book, Boydell was at pains to stress that he always felt in some way excluded in Ireland because of his English education, his English accent and his Moravian Protestant religious background. It doesn’t quite square with the fact that he held various official positions throughout his career and received such commissions as the official composition to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the 1916 Rising or the commission to write the official arrangement of the national anthem, and one cannot help wondering how much of this was a projection of Boydell’s or even a result of his personal behaviour. In a rare candid moment in the memoir he notes that ‘a portion of that patronising British superiority that I so much resented at Rugby had invaded my subconscious thinking’ and he recalls occasions when he ‘didn’t entirely hide a certain arrogance.’ Starting with a broadcast talk on 3 January that he describes as being framed ‘in a very exaggerated way to annoy people’ there are many examples of this in the diary, some of them already outlined above. More intriguingly, we get to see his explosive response when Acton suggests that the DOP give a concert with Our Lady’s Choral Society ‘to explode the idea that we are a Protestant orchestra.’ Boydell dismisses this as a ‘monstrous’ sacrificing of principles adding ‘we’ll be off to give a concert in Rome next in aid of the suppression of communism!!’ He refers often to the religious bigotry in Northern Ireland but takes offence when someone states that the problem with being in Northern Ireland is that it immediately matters what religion you are. Boydell seems to see his rather comfortable position in the Republic as being similar to that of Northern Catholics. After a discussion regarding work ethic with the Czech violinist Jaroslav Vaňáček, he sums up his feelings stating ‘The Catholics not only can’t think for themselves, but they are also incapable of real work.’ When his singing pupil Denis Donoghue naively ventures the opinion that one should not listen to the opinion of any teacher other than the one you are studying with, Boydell decides he has ‘the typical Irish Catholic attitude of unquestioning faith in one teacher alone.’ Revelation of Donoghue’s devotion to his teacher makes one wonder if Boydell had any input into Donoghue’s famous 1955 article on The Future of Irish Music in which all almost Irish composers were completely dismissed (with some exception made for Boydell). Certainly, Donoghue’s idea that the low quality of Irish composition was due to ‘the trap of folk music’ sounds like pure Boydell.

Exaggeration

Editor Barra Boydell provides footnotes identifying the various people mentioned throughout, though in a number of places where some context might have provided clarity, such as at the opening of the diary where many vituperative comments are made regarding some sort of disagreement among the members of the MAI, or when Boydell mentions that the board of the Royal Irish Academy are after John Larchet’s blood, we are left entirely in the dark. Barra treats the work with a leniency which is only to be expected considering his filial relationship. However, his addition of a footnote in the memoir where Boydell claims that pictures of Tibor Paul in hospital appeared on the front of every newspaper, to suggest this was ‘perhaps a slight exaggeration’, makes one wonder if he actually considers the rest of the volume to be factual. There are a few editorial issues, most notably the fact that at some point in the production process the page numbers were changed and so most references in notes to other pages of the book are two pages out. In the editor’s preface he declares that ellipses are used to indicate editorial omission of text and in his opening note states that private purely family matters have been omitted. Sometimes the positioning of these ellipses makes one wonder if it is not just family matters that are being omitted, such as on page 159 where it would seem to be musical discussion that has perhaps been trimmed. It would also have been interesting if an indication was included of what percentage of text had been cut. The index omits a number of figures mentioned in the book and is not entirely thorough about those things it does include. The volume is handsomely produced by Cork University Press under the Atrium imprint and illustrated with copious photographs of Boydell in the varied guises of musician, motorist and fisherman.

While the memoir will be of little use to anyone, the diary to a certain degree rounds out the picture we have of Boydell. Many years later composer James Wilson recalled Boydell as someone who got things done rather than someone who just talked and for this reason Boydell will always be an important figure in the history of the Irish music scene. However, the volume acts as a warning to those who might be tempted to use Boydell as a primary source for this period as has so often happened in the past. The highly exclusionary nature of his narrative in which he implies that nothing of interest happened artistically in Ireland until he and his friends got to work should immediately raise anyone’s suspicions. Barra Boydell’s repeated description of his father as one of Ireland’s foremost composers is understandable but his uncritical repetition of his father’s simple equation of modernism with disdain for traditional music and refusal to interrogate the ideas more thoroughly is in this regard disappointing. His preface promises a further volume of essays derived from a centenary conference held in 2017 and it is to be hoped that this will be the rigorous academically critical volume the topic deserves.

Rebellious Ferment: A Dublin Musical Memoir and Diary by Brian Boydell and edited by Barra Boydell is published by Atrium/Cork University Press. Visit www.corkuniversitypress.com.

Published on 21 January 2020

Mark Fitzgerald is a Senior Lecturer at TU Dublin Conservatoire.