To Copy is to Create

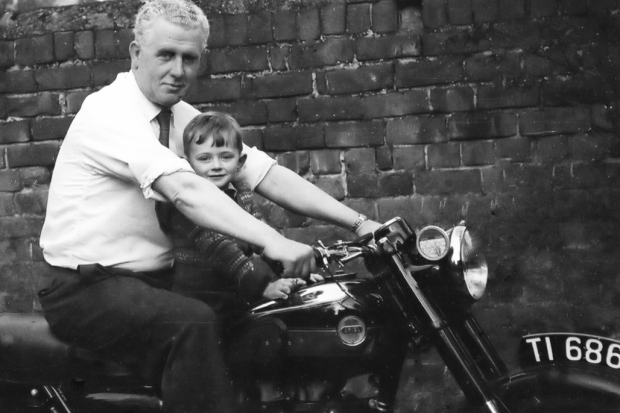

In the previous issue of the Journal of Music, the composer Bill Whelan argued that creators need to stand up and fight for stronger copyright, stressing the need for ‘copyright protection as a foundation for future creativity and a cultural economy’. The content industry tells us there’s a war on copyright, that the rise of digital technology must be tamed through stronger intellectual property laws in order to protect artists and creativity.

But I don’t believe this war is being fought for me as a composer. If anything, it seems that now is the time to fight for weaker copyright in order to allow new models to flourish. The information age presents us with a bewildering array of possibilities for community and the sharing of ideas, possibilities that often fly in the face of existing business models and the copyright laws that protect them. The internet is fundamentally incompatible with copyright because it is a system designed solely for fast, efficient copying, but out of that system arises the greatest space for sharing and learning that humankind has ever known. What is important now is that the industry allows this innovation to happen, and try to find its place in it rather than fighting to maintain its monopoly position. More importantly, creators must embrace this new paradigm, to explore and innovate.

If we are to debate the strengthening of copyright laws, we need to ask if copyright is always a good thing. It certainly has a place in the cultural ecology, but over the years it has been stretched too far. Copyright is not a natural property right of creators. It is a government granted monopoly that gives the rightsholder (sometimes this is also the creator, but most likely it’s a record company or publisher) certain rights over distribution, publication and adaptation for a limited period of time, before the work enters the public domain and becomes a part of the commons, usable by anyone. This is to encourage artists to make new works, and to drive innovation and creativity. The balancing act in copyright is that both the rightsholder and society should gain from the work, hence the right is granted only for a limited time.

Copyright extension is an effort to maximise the returns of the rightsholder at the cost of society and the public domain. Lawrence Lessig, a professor of law at Stanford University, has written a series of books which argue against such ‘cultural monopolists’, and how they engender a ‘permission culture’ – a culture in which creators get to create only with the permission of the powerful, or of creators from the past. In copyright, the concept of the limited term implicitly accepts a basic fact of creative enterprise: everything we make is based on the past in some way. Culture is an evolving conversation in which the creations of one influence those of others. To put a sticker on it that says ‘you may not copy this’ is antithetical to culture and art. So the limited term means that the rightsholder has a monopoly on profiting from their work before it reaches the public domain. Increasing the copyright term undermines this balance, providing short-term gain to the few at the expense of everyone else.

The Gowers Report, commissioned by the UK government in 2006, addressed a proposed term extension of copyright for sound recordings. The report found that this would be bad for the economy, bad for innovation and bad for creativity, and it ultimately advised the government to reject the proposal. (In a later interview, the report’s author, Andrew Gowers, said that the economic analysis actually made a case for reducing copyright term length.) The Gowers report was subsequently ignored by the government, prompting many to question why elected officials were choosing to ignore independent research in favour of industry lobbying. They described the proposed extension as one ‘whose prime effect is to benefit major label shareholders and a few, already highly successful, artists, while imposing significantly greater costs on new creators, the general listening public and the custodians of our cultural heritage.’

The most galling part of all this was the music industry’s attempts to frame the copyright extension debate as a moral issue, with the pro-copyright lobby and politicians selling the extension of copyright as something that would benefit poor session musicians from the 1960s. This was disputed by, among others, the Open Rights Group whose own analysis of the European Commission’s figures showed that an overwhelming majority of performers stood to earn up to only €27 per year under the extension, while record labels would collect up to €4.1 million per year. All of this is part of the slow deformation of copyright by the content industry, eager to extend it into any space where it may generate profit. The US copyright lawyer William F. Patry puts it this way:

Copyright law has abandoned its reason for being: to encourage learning and the creation of new works. Instead, its principal functions now are to preserve existing failed business models, to suppress new business models and technologies, and to obtain, if possible, enormous windfall profits from activity that not only causes no harm, but which is beneficial to copyright owners. Like Humpty-Dumpty, the copyright law we used to know can never be put back together again: multilateral and trade agreements have ensured that, and quite deliberately.

The enforcement of copyright law is just as anti-consumer. As Canadian journalist and author Cory Doctorow writes:

Copyright law valorizes copying as a rare and noteworthy event. On the Internet, copying is automatic, massive, instantaneous, free and constant. Clip a Dilbert cartoon and stick it on your office door and you’re not violating copyright. Take a picture of your office door and put it on your homepage so that the same co-workers can see it, and you’ve violated copyright law, and since copyright law treats copying as such a rarified activity, it assesses penalties that run to the hundreds of thousands of dollars for each act of infringement.

Doctorow ‘copyfights’ because copyright law, which used to be an industrial concern, is now being used as a cash cow for corporations. People want to share culture, and the internet is an easy way to do it. Remember mixtapes, sharing copied videos, burning a CD for a friend to check out an album you love? If you ever did that then you’re infringing copyright, and if the content industry can prove it, then they may fine you for €55,000 per song. Doctorow’s argument is that copyright is a wholly improper way to combat something that no-one has ever proved harms the industry. The cry from the record and movie corporations each year is that their business is under dire threat from piracy and technology. They have railed against every innovation that they could not control, from video (‘the Boston Strangler of the movie industry’) to MP3s. In truth, the industry enjoys record profits in some sectors at the moment. Just last month, Will Page and Chris Carey, economists from the UK’s PRS for Music, released a report showing that the music industry in the UK is not shrinking, but growing: a 4.7% increase this year in the ‘value of music’. As they say, ‘the pie just got bigger.’

Perhaps it’s time for copyright to be reined in, or at least be retrained to its original purpose, but what are the alternatives? The information age presents creators with an abundance of opportunities both to collaborate and to monetise their work –and these do not have to be mutually exclusive concerns. Some artists use the old model of selling content directly, others find new ways of connecting with fans and giving them reasons to buy. Michael Masnick, founder of the weblog Techdirt argues that the industry would serve itself and consumers better by concentrating on developing new business models rather than wasting time and resources on protecting existing ones. Masnick points to a wealth of musicians who have reacted to consumer demand by letting free and infinite goods such as digital files actually be free and infinite, while making their money from scarce goods such as concerts and physical artefacts. The more the music is heard, the more fans the artist has, and the greater the opportunity to sell whatever the fans are willing to buy.

As a composer, I do not worry about my work being stolen, or that other people will make money from it and I won’t get a cut. These risks are exaggerated, and I would rather my music was out there and part of the conversation, than corralled and protected. Theft seems trivial beside the possibility that my work will be irrelevant, ignored and unheard. But if musicians worry about being ripped off, then they can licence their work through Creative Commons or the General Public Licence (GPL). Both of these are forms of ‘copyleft’, freely distributed licences that allow a creator to remove the barriers to sharing and collaboration that are put in place by copyright. As the Creative Commons website explains, they aspire ‘to cultivate a commons in which people can feel free to reuse not only ideas, but also words, images, and music without asking permission — because permission has already been granted to everyone.’ The advantage to the creator is that the work can be freely copied and shared without infringing copyright, but the author maintains whatever rights they choose, including attribution and commercial options.

There is no ‘war’ on copyright, merely an effort to restore the balance between the needs of business and the needs of art by standing up to further distortions of the copyright principle. I agree with Bill Whelan’s call for creators to stand up and be counted, but they should also take a long, hard look at why they create and who they create for. A rich cultural ecology needs balance to thrive. Locking creativity behind a gate of legislation makes work for lawyers, not artists.

Lawrence Lessig’s book Free Culture is available for free from his website, www.lessig.org; Cory Doctorow’s book Content is free to download from his site craphound.com. William Patry’s blog is available at www.moralpanicsandthecopyrightwars.blogspot.com

Published on 1 October 2009

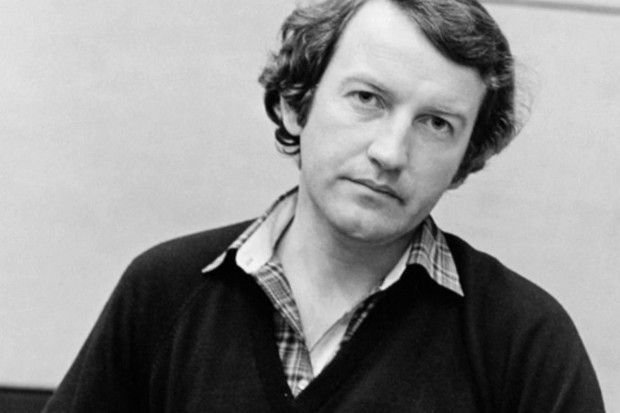

Scott McLaughlin is an Irish composer.