Home Sweet Home: Classical Music Culture in Ireland, Britain & America

As we raise our eyes from our own island, some of the great imperial powers of Europe heave into view: Britain, a superpower for centuries, with a mixed musical history, but a long history of court life and imperial display; France, also a world power for centuries, where institutional grandeur, including its musical forms, has been passed from royal to imperial to republican regimes, from Louis XIV down to the present day; Germany, at the centre of the history of classical music from the time when it was a jigsaw of empire and principalities to today. But is this the only direction in which we should be looking as we seek to understand our history? Across the Atlantic is another country which separated itself from the British Empire, which organised itself as a populist democracy, which deliberately renounced the aristocratic traditions of the imperial centre, and in which the conditions prevailing in the period of national formation meant that, where classical music was concerned, the culture prevailing in the major European powers would not easily be replicated.

The title of Joseph Horowitz’ Classical Music in America: A History of its Rise and Fall (W.W. Norton, 2005) immediately catches the attention. Whether our interest lies in the great orchestras or in composers in the classical tradition, it would be hard to ignore the American contribution to the history of classical music over the last half-century at least. At this remove, we may be a little vague as to the details of the rise of American classical music, unclear as to when exactly it peaked and unaware that it has fallen. What, in the broadest terms, is Horowitz suggesting? His principal concern is with the attempt to implant classical music in the body of American culture. He considers that in the early decades of the twentieth century an opportunity was lost to move from a reasonably well-established but ultimately borrowed European culture to an autonomous, truly American development of classical music.

A number of related assumptions are at work here. Firstly, that when classical music is transplanted from its European base, it is not sure to flourish. Secondly, that it needs tending if it is to adapt to a new climate. Thirdly, that its health and future are assured only when it has rooted itself in the new soil and has become part of the broader ecology of its new home. About one hundred years ago, on this side of the Atlantic, a work was published that reflected many of the same assumptions. In its third chapter, titled ‘Foreign Dominations’, the debilitating effect in earlier years of the popular overvaluation of foreign performers was deplored; as was the excessive influence of some foreign composers on the native talent. The book concluded with a call for the public ‘to set the example of appreciating native attainment, if that attainment is ever to enjoy […] the wide recognition of the rest of the world.’ The writer was not Douglas Hyde but J. A. Fuller Maitland, author of English Music in the XIXth Century.

One possible reason why some prominent Irish writers on music do not wish to deal with the British dimension is that it would force them to think beyond the aggravated form of historical revisionism to which they are wedded, one that ascribes all Irish cultural failures to the negative effects of a nationalism automatically defined as insular, narrow-minded, irrationally anti-British and culturally anti-European. Furthermore, full consideration of the British story would undermine the simplistic Ireland (negative)/Europe (positive) model which encourages these writers to see themselves as brave beacons of cosmopolitan enlightenment amid the insular gloom. Taken together, the British, Irish and American stories reveal a number of shared motifs. What is interesting then is to see the different ways in which these motifs are articulated and the way in which these stories comment on each other.

Classical music cultures

The reasons for the devaluation of music in eighteenth-century Britain need not concern us too much here. Certain factors are commonly cited: the Puritan reaction against what was perceived as the licentiousness and excess of Restoration England; the devaluation of music to the status of a pleasant but insignificant – if not actually dangerous – social diversion within Lockian philosophy and within the pragmatic, business-minded culture of the time; and the indifference of a still powerful aristocracy to the general state of native musical culture. As a result, musical education was neglected and a culture of hollow virtuosity, extravagance and sentimentality held sway in the theatres, along with a preference for imported musical styles and musicians. (This was, to a large degree, the culture that prevailed in Irish urban centres as well.) It was only through a century-long effort that riots and unruliness were largely banished from the theatre, that music was rehabilitated for the middle-classes as an elevating art, that music education began to be taken seriously, that a reaction against imported models in favour of an emerging English/British school of composers began to take root and that – under impulses sometimes idealistic and sometimes socially manipulative – the opening of the music to the working classes was taken seriously.

With Joseph Horowitz as our principal guide, let us look at the culture of classical music in America during the same period. The New York scene in 1827 differs little from its equivalent in London or in Dublin, where cuts, insertions, interpolations and other forms of mangling were routinely inflicted on musical works:

Maria Garcia married in New York, and as Maria Malibran blossomed as the first local diva. When her father’s troupe departed for Mexico, she stayed behind to sing English [i.e. English-language] opera at the Bowery Theater alongside singers who scarcely knew a word of their parts. She gamely prompted her colleagues, and cleverly interpolated ‘Home Sweet Home’ into Rossini’s lesson scene in The Barber of Seville… As Zerlina, she played opposite a Don Giovanni who did not even attempt to sing. (p. 123)

Much of the first third of The Rise and Fall is structured around the contrasting cultures of Boston and New York. As mentioned above, in Britain the nineteenth century witnessed a gradual elevation in the status of classical music. The sacralisation of classical music was almost a necessary condition of its growth in Boston, where the Puritan ethos rejected frivolous display and valued only a plain art at the service of morality. The vocabulary which had surrounded New England hymnody – a key strand in American musical history – was adapted and intensified by John Dwight Sullivan in mid-century as he worked to build an audience for the European classics:

I hazard the assertion that music is all sacred; that music in its essence, in its purity, when it flows from the genuine fount of art in the composer’s soul, when it is the inspiration of his genius, and not a manufactured imitation, when it comes unforced, unbidden from the heart, is a divine minister of the wants of the soul. (Horowitz, p. 26)

Here, the romantic cult of the artist as lonely seeker after truths in a hostile or indifferent universe is removed from any association with the messy realities of the artist’s actual existence. The work of art – Dwight’s concern is with the masterworks of the Germanic instrumental tradition – transcends the conditions of its making. As a kind of prayer – Dwight goes so far as to call it ‘a sort of Holy Writ’ – it can overcome the New England Puritan distrust of secular art and take its place at the centre of Boston culture. In future decades it will be able to draw on the wealth and patronage of a very Europeanised elite as orchestras are founded and concert halls are built. The best musicians and conductors will be sought – most of them, throughout this period, imported from the German-speaking world – in order to ensure the perfect performance of this musico-religious experience. And the Boston Symphony will set a standard of proficiency and professionalism that astonishes Europe as well as North America.

Irish and American stories

One of Horowitz’ central concerns is with the difference between a performance culture – in this case, a kind of museum culture imported from Europe – and an autonomous, creative, American culture. Thus, while drawing sympathetic portraits of those who gave so much time and energy to the building of a musical infrastructure for their city or country, he is aware that for classical music to be a living part of American culture requires American musicians, American conductors and American composers able to draw on the experience of their own country to forge an American idiom.

From our point of view, it is noteworthy that the attempt in this period to find a national idiom within the international world of classical-music language is the rule rather than the exception. In Britain, with the physical, educational and intellectual supports in place towards the end of the nineteenth century, composers begin to produce music that speaks for itself instead of palely echoing Mendelssohn or Brahms or Wagner.

The American story is more complex. Boston, of course, is not America, but the Boston story is quite revealing. The way in which music was listened to there was rooted in its own culture. On the other hand, not only did the Germanic repertoire reign supreme, but, as elsewhere in the United States, a preponderance of orchestral musicians were themselves German. (It was only with the outbreak of anti-German feeling as the United States entered the First World War that English became the working language of certain American orchestras.) Though a school of composers did emerge in the late nineteenth century, it was not going to set the American scene alight. Horowitz argues strongly for George Whitefield Chadwick’s merits as a composer; he is intrigued by the fate of Amy Beach, but is more critical of her music. (What little I have heard of these composers would lead me to tilt the balance back a little towards Beach.) Horowitz notes the parallel with the Boston literary scene, where refinement and intellectual curiosity failed to produce much great literature.

Boston speaks indirectly to the Irish experience in another way. A bastion of WASP culture, it was able to manage a small Irish and other immigrant intake. As in Victorian Britain, there was in certain quarters a wish to spread the joys of classical music and other forms of respectable culture to the general populace. Such benevolence was to come under serious pressure:

In 1847 alone, Boston, which had been receiving immigrants at the rate of 4,000 to 5,000 a year, absorbed 37,000 new arrivals; by 1900 35 percent of the population was foreign-born; more than 70 percent was of foreign parentage. The immigrants, mainly half-starved and unskilled Irish, stoked new Boston industries. As of 1860, factory wages were $4.50 to $5.50 a week; in New York, where production was not yet mechanized, wages ranged from $8.00 to $10.00. Impoverished, debased, brutalized, the Boston Irish would not become cultural citizens.

The Brahmins bravely set to work, attempting to assimilate this alien species. But Irish interest in elite culture was limited, and the Brahmins lost heart – and with it, a portion of their idealism. (p. 96)

The Irish who arrived in the famine period were impoverished and largely rural; some were or had been Irish-speakers. They would not have seen any elite culture except through big house windows. From a struggle for life itself in rural Ireland, they found themselves in a new country, struggling for survival in a strange urban environment. It is hardly surprising, then, that they were not a receptive audience for classical music. One could react to the alienation of the Boston Irish from classical music with embarrassment and ask: what is it in the Irish psyche that leads to this failure to reach correct international levels of cultural activity? This is the emotional logic behind the attitude of some of our leading writers on classical music in Ireland to a similar failure on the part of the Irish at home. Whether we be concerned with Boston or Banteer, however, the question – and the embarrassment – is misplaced. For Horowitz, this is a side-issue to the main subject of his book. He is not, however, afraid to lay out the socio-economic facts and to relate them to the cultural life that he is examining.

Whether consciously or unconsciously, our own school of cultural historians cannot bring themselves to acknowledge the socio-economic facts surrounding their subject of study. To look honestly at the social and educational bastions of classical music in Ireland in the early to mid-nineteenth century would involve recognising a culture far less generous than that of Boston, with little missionary fervour (as in a willingness to go out and work to build a public), with little interest in moving outside a society that revolved around Trinity College and the Cathedrals (see the careers of Sir Robert Stewart or of Olinthus J. Vignoles), and with little questioning of its own beliefs, social attitudes or political allegiance and affinities. Rather than face these uncomfortable questions, it is easier to posit a peculiarly rabid Irish form of musical nationalism as principal and almost sole cause of the failure of an autonomous classical music culture to develop. To weigh the impact of musical nationalism, it would first be necessary to face up to the nature of Irish society in this period, and to acknowledge the ways in which language, class, political power, geography (regional, rural/urban), religion and education affected cultural life and aspirations.

One small episode mentioned by Horowitz opens up a broader American perspective without losing sight of the British and Irish dimensions:

At the Astor Place Opera House [in New York] in 1949 […] a fight broke out between the partisans of the English actor William Charles Macready and the American actor Edwin Forrest. Macready was aristocratic. Forrest was a patriotic populist.

Twenty-two people were killed when militiamen fired into a huge crowd that was attempting to storm the opera house. According to Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States, the rioters were largely Irish, and shouted, ‘Burn the damn den of aristocracy.’ The Famine-swollen Irish population, Catholic, wretched and angry, suffered discrimination and sometimes violence from the established Protestant white working-class. The Irish immigrants themselves became racist towards blacks and the various waves of incoming immigrants. In a society where employers were able to use the law, the police and the guns of militia and army to break strikes and to enforce exploitation and wage-slavery, where opportunity walked hand in hand with disaster, the attitudes fostered by Irish social and political realities were easily translated into the populist language of American culture.

Rise and fall?

When a talented composer like Stanford emerged in Ireland towards the end of the nineteenth century, his religious and political affiliations, as well as the greater opportunities available, led him to move to England at a young age and to devote his energy to the renaissance of English music. His Irishness was important to him but within a British political context; musically, it remained a matter of local colour. Around the same time in the United States, those who wanted to see the emergence of an American school were aware that their composers were still imitating the language of the European masters. Horowitz writes illuminatingly on the attempt to kick-start an American national school by importing Dvorak, a butcher’s son who had given a musical voice to Czech national feeling. There were mixed reactions to Dvorak’s absorption of black and native American music in his New World symphony. The implicitly positive valuation of non-white cultures was a challenge to a society that was diluting, if not actually reversing, the promise implicit in the abolition of slavery. New York was more welcoming to Dvorak than Boston. Horowitz quotes William Althorp, after the Boston premiere on 29 December 1893, from the Boston Transcript:

[T]he great bane of the present Slavic and Scandinavian schools has been the attempt to make civilized music by civilized methods out of essentially barbaric material. [O]ur American Negro music has every element of barbarism to be found in the Slavic or Scandinavian folk-songs; it is essentially barbarous music. (p. 7)

Seventeen years later, another prominent Boston critic, Philip Hale, was still expressing exasperation at the idea ‘that the future of American music rests on the use of Congo, North American Indian, Creole, Greaser and Cowboy ditties, whinings, yawps, and whoopings.’ (p. 8)

Amy Beach’s response to Dvorak is pitched differently:

Without the slightest desire to question the beauty of the negro melodies of which [Dvorak] speaks so highly, or to disparage them because of their source, I cannot help feeling justified in the belief that they are not fully typical of our country. The African population of the United States is far too small for its songs to be considered ‘American’. (p. 7)

The generous interpretation of this passage would see Beach not so much rejecting ‘negro melodies’ as saying that that they are not representative or truly national. In any case, Beach – who decades later was to write a string quartet based on Eskimo themes – was impressed by Dvorak’s achievement and, looking to an element in her own family background, was soon at work on her ‘Gaelic’ symphony, which combined Irish melodies with material of her own in an Irish-tinged medium. This was called the first significant American symphony by the old Percy Scholes Oxford Companion to Music. It can stand alongside the more successful attempts to marry Irish folk elements and classical forms.

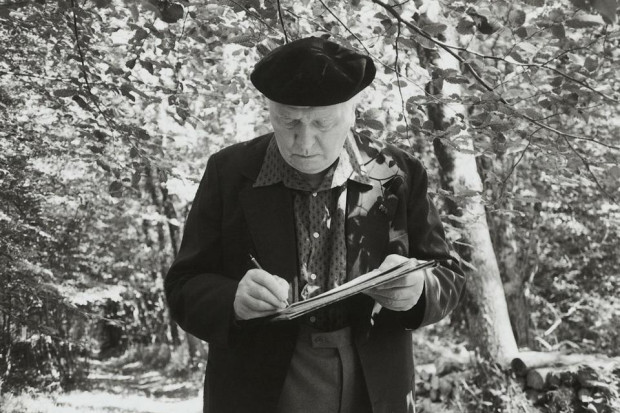

Attention to the social and political context of music-making of various kinds does not imply a form of musical determinism. The context shapes much of the practice of music, but musical affinities can be elective, and one of the joys of art is that it allows us to move imaginatively out of the worlds we have inherited. Dvorak can cross the Atlantic and become, for a time at least, an American. From the drawing-rooms of Boston, Amy Beach can attempt to connect with peasant Ireland. And the imaginative criss-crossing between Britain and Ireland of Stanford, Bax or Moeran could also be cited here.

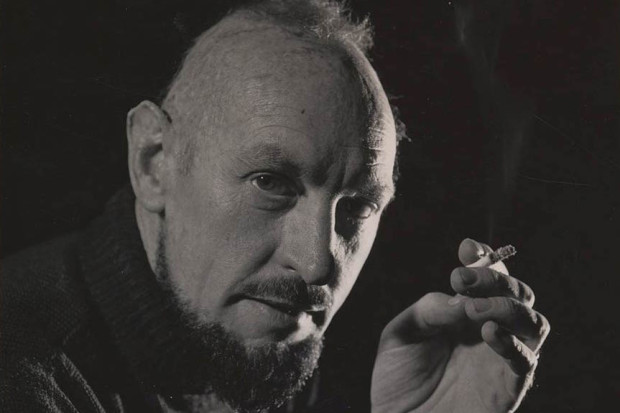

A clearly defined American school of composition never did emerge. Charles Ives was the nearest to being a musical Whitman, opening himself to the energy, breadth and multiplicity of the new American experience and being impelled to transform the artistic language he had inherited. Sadly for him, America – still in thrall to European models – was not yet ready to listen. Horowitz believes that a historical opportunity was lost when the dominance of the Germanic repertoire and of German musicians and conductors was broken. However, the years after the First World War witnessed a new wave of showman conductors like Toscanini who would endlessly repeat the classics of the European repertoire. Serge Koussevitsky’s interest in promoting new music by American composers was very much the exception. In addition, the arrival of Schoenberg and other musical refugees from Nazism would pull the young American avantgarde back towards European models and solutions.

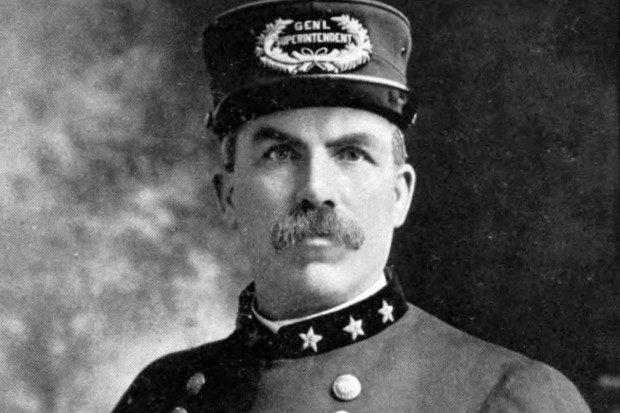

Horowitz has been an excellent guide to many aspects of the nineteenth century. As we move away further into the twentieth, his fascination with the history of performance in America – he is the author of a massive study of Toscanini and his influence – leads him to devote excessive space to the internal history of various orchestras and their conductors. This will be of great interest to readers who share his fascination, but the sense of connection to the surrounding society – and indeed to other forms of music – is almost lost. He eventually comes around to dealing with American composers and to forms such as the musical, but he appears less engaged with his material than in the earlier sections. Two major problems arise, one internal to the book, the other external. First of all, the argument for a rise and fall of classical music is not sustained. From the touring performers of the turn of the nineteenth century, through Patrick Gilmore’s massive post-Civil War Peace Jubilee, and on to the latest virtuoso import or the Three Tenors, the story is one of a sustained cult of performance. Focusing on major orchestras, Horowitz does not integrate into his story the state of music education, the number and level of school and university orchestras or the level of amateur activity (at home, in halls or in churches). Without such information, it is therefore difficult to assent to his closing thoughts, when he announces that the history of classical music as a prestigious form is over, that we are now in a post-modern age and that the time has come to open up to all forms of music. (It should be mentioned here that Horowitz has done very imaginative work in reaching new audiences and programming different kinds of music for the Brooklyn Academy.)

Like a conductor’s final flourish, the idea of a historic break brings the book to a dramatic close. But this is where we have to step back from the book and ask ourselves if, even where aspects of the nineteenth century are concerned, if it is true to American musical experience. Given that the United States was already a multi-ethnic state in the nineteenth century, that its life as opposed to its elite arts has for centuries marked it off from Europe, that from New Orleans, along the Appalachians to New York, and across to New Mexico or Nebraska, its experience has been interpreted and cross-fertilised in numerous and ever-evolving idioms, by musicians of every class and colour, it must be wondered whether a history of classical music that rarely lends an ear to the noise coming from other rooms in the house of music, and which does not look out the window at the massive cultural statement made by the streetscape and human energy outside, is truly capable of addressing the American experience. Horowitz tells a very interesting story, but there are other ways of telling it.

In a populist democracy, where (to adapt the title of Arno J. Mayer’s book) the persistence of the old regime is not a major shaping factor in cultural life, classical music will not automatically be granted the status it has in the old powers, where cultural memory is different and where cultural hierarchies are taken for granted. As we have seen, Britain was able to draw inspiration from the period from Byrd to Purcell and eventually to restore classical music to a position of relative honour. In the United States, despite its colonial inheritance, classical music would have to find a place in a culture that tended to look forward rather than back. There was no guarantee that inherited European forms – political or cultural – would be adequate to the new conditions of life. American composers have produced wonderful music, but they have also been pulled towards the culture of performance descibed by Horowitz, towards exasperated rejection of that culture and an embrace of the European avantgarde, towards dialogue with other forms of music, towards new forms of invention, and so on. To grasp the multifarious nature of American musical experience, and to grasp the place of classical music within it, we may need to turn to Richard Crawford’s America’s Musical Life, a work driven by a generous, truly democratic impulse.

The Irish story differs from the American one in many ways, but Ireland too is a populist democracy. Like the best of commentators on American culture, however, we would do well to acknowledge the nature of our political and cultural inheritance. Whatever their frustrations, those who love classical music or its contemporary forms will not get very far if they do not acknowledge that they are sharing a democratic public space with other forms of musical culture and that generosity of spirit and constructive engagement will achieve more than wounded admonition. In this regard, we may draw as much inspiration from across the Atlantic as from our European neighbours.

Published on 1 November 2006

Barra Ó Séaghdha is a writer on cultural politics, literature and music.