The Little Ponies that Beat the Mare: Thomas Moore and his Irish Melodies

Gone are the days when all Irish school children would learn Thomas Moore’s Irish Melodiesz as a matter of course. Moore has disappeared off the radar and I suspect most young people would be hard pressed to recall the airs, let alone the words, of any of his songs, for example, ‘The Last Rose of Summer’, ‘The Minstrel Boy’, ‘The Harp that Once Through Tara’s Halls’ or ‘The Meeting of the Waters’. How many of us from a somewhat older generation could name any number of titles? It might be surprising to discover that Moore wrote no less than 124 songs, and this year, in celebration of two hundred years since the first publication of the Irish Melodies, a year-long diary of events will acknowledge Moore’s achievement. The line-up includes a competition for young singers, two world premiere recordings, a major exhibition, performances and linked conferences.

The Irish Melodies

The unique quality of the Irish Melodies and Moore’s genius lay, in part, in the music he chose. The airs were drawn largely from the anthologies of ancient harp music, particularly the collections of Edward Bunting, published after the Belfast Harp Festival in 1792. The songs gave them new life and a symbolic meaning and brought this music before a wide audience for the very first time.

Over the years, misconceptions have grown up in relation to the Irish Melodies. Moore wrote many songs which were published in various collections, but he consistently reserved the Irish airs for his Irish Melodies. A number of songs are widely regarded as Irish Melodies, whereas in reality they were published in other collections. For example, Moore’s poetry for ‘Love Thee Dearest’ is set to a melody by Giovanni Battista Viotti and the song ‘Oft in the Stilly Night’ appears in A Selection of Popular National Airs, as its air was regarded as Scottish. One of the most frequently performed songs today, ‘She is Far From the Land’, is not usually sung to Moore’s original air (‘Open the Door’), but has taken on a life of its own in a completely new setting by Frank Lambert. Similarly, ‘At the Mid Hour of Night’ is to be heard in two different versions, one is the original from Moore’s fifth collection published in 1813 to the air ‘Molly Dear’, while the other has a new melody and accompaniment composed by Frederic Hymen Cowen.

The Irish Melodies were published between 1808 and 1834, in ten volumes for the publishers James and William Power, two brothers, one of whom operated in London while the other was in Dublin. The accompaniments for the first seven volumes were written by Moore’s good friend Sir John Stevenson. Stevenson was a prominent figure in Dublin musical life and his partnership with Moore brought him further celebrity. As soon as the Irish Melodies began to appear, however, controversy surrounded the piano arrangements. They were considered to be too elaborate and out-of-step with the simple beauty of the airs and, in the North, Moore was accused of stealing Bunting’s thunder. But despite these problems, the Irish Melodies were instantly celebrated, something that took Moore somewhat by surprise. It seems the mixture of evocative traditional airs and Moore’s atmospheric lyrics proved absolutely irresistible to audiences; and so, his fame was sealed as they soon began to make their way around the world. When the Power brothers fell out, Sir Henry Rowley Bishop was approached to write the accompaniments for the remaining volumes.

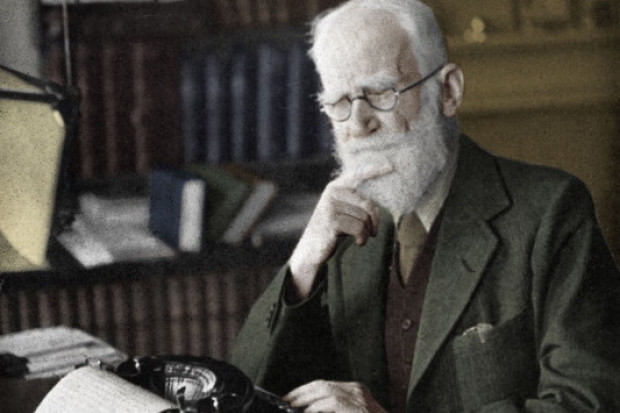

Moore’s biographer Howard Mumford Jones has suggested that the success was due, in part, to the neatly sized volume which sat happily on the music desk of the smaller and more delicate pianos of the period. The title page was decorated with a shamrock border and the picture of a harp, a potent symbol which recurred on later volumes. One shows a bearded minstrel sitting at the side of the road with a small knee harp, conjuring up reminders of Carolan or other harpers who went before him. Another volume portrays the powerful image of the muse of Ireland, with classical draping over her womanly form, yet wearing a helmet in readiness for battle while her arm rests nonchalantly on the harp at her side. The imagery of the harp also provided inspiration for Moore’s poetry. One has but to think of ‘The Harp That Once Through Tara’s Halls’, ‘The Origins of the Harp’, ‘The Minstrel Boy’, ‘The Farewell to My Harp’, ‘Shall the Harp Then Be Silent’ and ‘Dear Harp of My Country’ to name but a few. Whether Moore ever played the harp or not is unknown, but he certainly owned one, now in the possession of the Royal Irish Academy in Dublin. Painted in an intense green shade, with gold shamrock decoration, it’s a beautiful example of a Royal Portable Harp, given to Moore by the renowned Irish harp maker, John Egan. That the harp was really Moore’s is unquestionable for it features in a painting by an unknown artist where Moore is centrally seated at his desk, surrounded by books and papers. On the left of the picture can be glimpsed a square piano, the period equivalent of the domestic upright, and resting on its side against the leg of the piano is the harp in question.

Other iconography relating to Moore is still to be found in Ireland today. Along with a number of other painted portraits, and a statue near Trinity College, there is also his personal library of almost 2,000 books donated to the Royal Irish Academy after his death. ‘Moore’s Rose’ is one of the most popular sights at the National Botanical Gardens. It was raised from a cutting taken in the garden of Jenkinstown Park, Co. Kilkenny, where Moore was reputed to have written ‘The Last Rose of Summer’. Then there is his Tree commemorating ‘The Meeting of the Waters’ in Avoca. Legend has it that this last song was written at Parnell’s home, Avondale House, although Moore seemed not to recollect this when asked sometime later.

The third President of the United States, Thomas Jefferson, was extremely fond of Moore’s poetry. Before his death in his last letter to his daughter, he quoted from one of the Irish Melodies: ‘It is not the tear at this moment shed…’ and he particularly loved ‘Oh! Blame Not the Bard’ and ‘Oh! Breathe Not His Name’, the latter written by Moore in tribute to his friend Robert Emmet who was executed in 1803. The former was a song that Moore used to explain his decision to leave Ireland: ‘But alas for his country! …‘tis treason to love her, and death to defend…’ One of the most beautiful and poignant songs is the sorrowful ‘She is Far From the Land’, a moving lament for Sarah Curran who had been engaged to Robert Emmet:

She is far from the land where her young hero sleeps

And lovers around her are sighing

But coldly she turns from their gaze, and weeps

For her heart in his grave is lying…

Moore wrote in his introduction to the Irish Melodies that he wished to reach the ‘pianofortes of the rich and educated’ so as to further Ireland’s cause. In the end he reached people of all nationalities from the gentry down to the most humble. ‘The Last Rose of Summer’ sold no fewer than one and a half million copies in the US and was undoubtedly among the most popular songs of the century. Indeed, it was likely to turn up in any programme or in the middle of an unrelated opera. Imagine the scene: rapturous applause for the soprano, she takes a bow and proceeds to halt the narrative on stage to give an encore; frequently it was a Moore song. Friedrich von Flotow used the air of ‘The Last Rose of Summer’ in his opera Martha and, as piano transcriptions frequently highlighted the most popular vocal music of the day, countless pianist-composers used it in their fantasias and variations. The list includes relatively familiar nineteenth-century names such as Mendelssohn, Thalberg, Herz, Moscheles and Kiallmark and a bewildering array of composers long since forgotten.

Of more significance, perhaps, is Moore’s influence on Berlioz and Schumann. Both employed Moore’s translated texts in their works: Schumann with his little-known Das Paradies Und Die Peri, taken from the second part of the oriental poem Lalla Rookh and Berlioz with nine of Moore’s songs under the title Irlande. Schumann’s work was performed by the Philharmonic Society in London and the English composer William Sterndale Bennett subsequently wrote the fantasie-overture Paradise and the Peri for the Philharmonic Subscriber’s Concert in 1868. Berlioz himself was enthralled with Moore’s songs and held romantic notions about Ireland, fuelled by his interest in the Irish actress Harriet Smithson, whom he married.

I was reminded of Moore just recently while viewing one of my favourite Looney Tunes cartoons. It features Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck, and Bugs has decided to display his prowess on the xylophone. Meanwhile, Daffy has wired a bomb to one of the notes, but Bugs continually makes a mistake in the tune. Finally, in frustration, Daffy decides to show him how to play the tune properly, thereby blowing himself up. What, you might well ask, has Bugs Bunny got to do with Thomas Moore? Well, the tune he chooses to play is none other than ‘Believe Me if All Those Endearing Young Charms’. Of all the millions of children and adults to have seen that cartoon, I wonder how many would have identified it as one of Moore’s Irish Melodies or pondered the reasons why it was chosen for the sketch. Be that as it may, Thomas Moore’s songs have stood at the vanguard of popular song for two hundred years. Surely, they are among our greatest national treasures.

Further information on Thomas Moore events can be found on http://conservatory.dit.ie.

Published on 1 January 2008

Una Hunt is a pianist, broadcaster and Irish music specialist, and Professor of Performance Research at DIT Conservatory of Music and Drama.