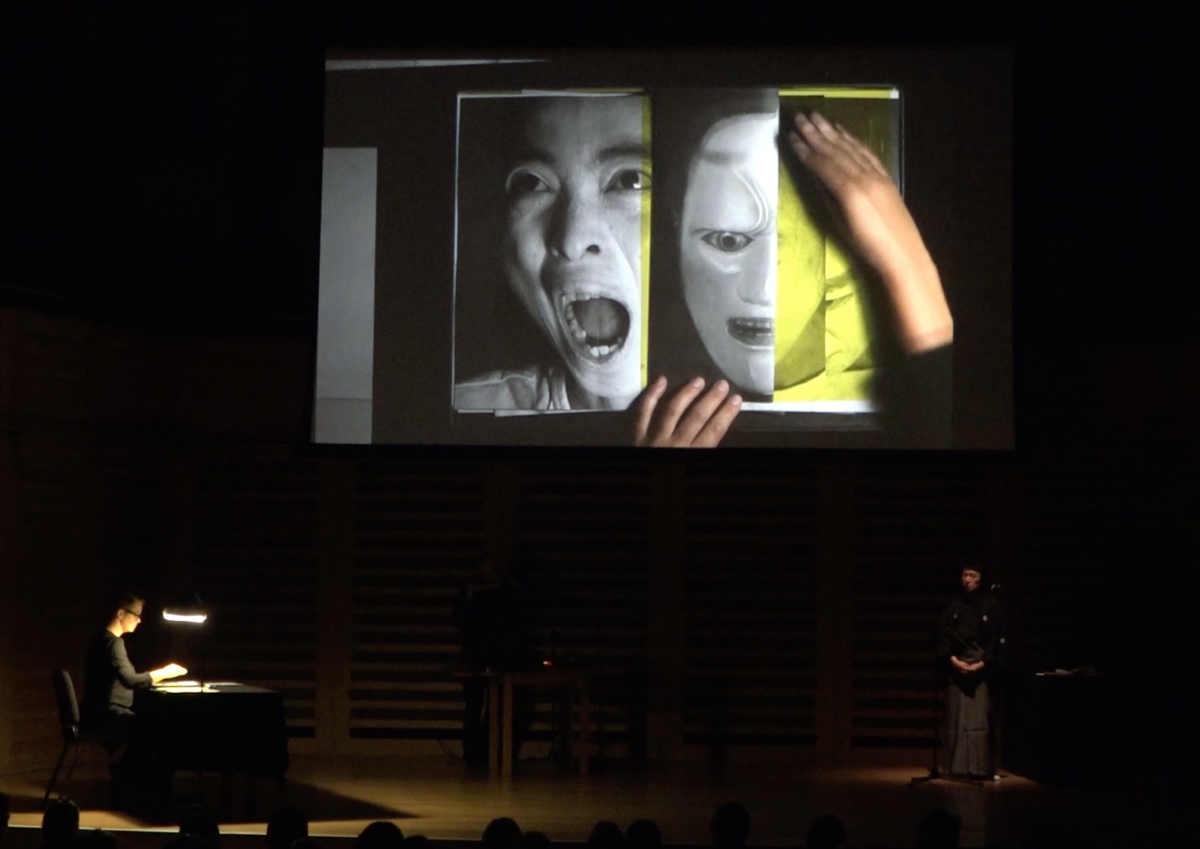

Masaki Umano performing the Noh ‘Izutsu’ (photo: Shitong Zhang)

Making the Invisible Visible

Noh is a traditional ‘total art form’ from Japan, a form of theatre that incorporates instrumental music, chant, voice, costume and movement. It is slow, ritualistic and difficult, formalised over 600 years ago, and yet it continues to hold a fascination for artists and musicians. Its influence can be felt in the work of Yeats and Beckett, or in the music of Benjamin Britten. I first encountered Noh during my Master’s degree when exploring the relationship of text and music, and since then it has held me in thrall: for me it is the way it communicates its ideas, how it combines abstraction and meaning. The influence of Noh is so widespread and varied in its manifestations that mu:arts, a Japanese cultural promoter, presented a packed two-day festival this summer at London’s Kings Place, called Noh: Reimagined.

Noh exists in a suspended state: its canon was largely codified in the 1300s, and ever since then it balances on a knife-edge between the heavy-handed prescription of its movements and sounds, and a freedom of interpretation and expression so subtle it is sometimes overlooked entirely. It is an Important Intangible Cultural Property in Japan, and therefore protected to ensure it continues to survive and be transmitted in its purest form, yet modern Noh performers and proponents are open to collaboration, experimentation and cross-cultural exchange.

Noh:Reimagined at Kings Place

Tension

This tension is what allows a festival such as Noh: Reimagined to be successful. Taking place over two days (29–30 June), it featured extracts from traditional plays, introductory talks and workshops about elements of the artform (varying from a basic demonstration about its movement style to the relationship between neuroscientific research and Noh practice), and contemporary works inspired by Noh. The Festival placed these all on one plane, and in so doing emphasises the ambitious and new, while never diminishing the traditional. Each element helped to illuminate every other.

Noh: Reimagined opened with a concert, called The Sublime Illusions of Mugen Noh, of extracts from traditional Mugen (dream-like, illusory) plays, centred around a moving han-noh (half play) performance of Izutsu (‘The Well Cradle’). Noh often seems at first impenetrable – the instrumental forces are three drums and a piercing high-pitched flute, playing complex patterns which incorporate rhythmic vocal ‘calls’ from the percussionists (imagine something like the kiai uttered in karate), over which is layered the main actor’s guttural vocal lines in classical Japanese, performed in a forcibly low register and with a free independent tonal centre. Add to this the stiff, formalised movement of the actor, wearing a mask with a fixed expression that blocks some of the clarity of the voice, and who is also elaborately costumed.

These elements are sometimes coordinated, sometimes not, but to the beginner seem to add up to little but chaos. And yet it is the charm of Noh that even a complete newcomer can quickly acclimatise to this soundworld, and begin to hear in it patterns and passion beneath the surface formality. The harshness of the sounds themselves and the intensity of their performance buoys you upwards to an extreme height of tension, washing you up onshore feeling sensitive and raw, and ultimately wide open to its grief, love and redemption. In the words of Professor Keizo Miyamoto, Noh makes the invisible visible.

Leon Michener and Yukihiro Isso

Rumbling and piercing

Unfortunately, it can also leave your ears feeling a little fatigued; following the main evening concert was a late-night improvisatory collaboration between nohkan (flute) player Yukihiro Isso and composer/pianist Leon Michener which my ears were already too worn out to fully appreciate.

The collaboration chiefly involved Michener creating deep, thudding ambient textures with live processing of the piano soundboard, over which Isso (designated an Intangible Cultural Asset) performed characteristically virtuosic solos with his collection of traditional flutes and woodwind instruments – sometimes with multiple instruments at once. The performance drifted in and out of effectiveness, at its height when the two musicians were in real dialogue, such as during an exchange of interjecting melodies of almost nursery-rhyme simplicity. Frequently though the two could not seem to reconcile their individual languages, and were playing against rather than with one another.

The dialogue between contemporary and traditional was at its most vibrant in the festival on the second night, where the main concert, The Transformative Power of Noh, included two new specially created works. These new pieces were set against one of the most advanced and difficult dances in the tradition, the visceral, energetic, almost violent Lion Dance from Shakkyō.

The Lion Dance was a perfect counterfoil to the abstraction and minimalism of the two new works. Clod Ensemble’s Snow was a piece of multimedia theatre, with pre-recorded narration and music – mostly consisting of a rich, dense choral texture and disappointingly cinematic orchestration, with only lighting and smoke machine standing in as ‘performers’. The influences of Noh on this piece were absent perhaps from its soundworld but present in its slow pacing and in the way it told its story – that of a claustrophobic relationship told by way of an extended avalanche metaphor – through sensory allusion, rather than direct exhibition.

Echoes and Callings

Echoes and Callings was a multimedia work from photographer Wiebke Leister and improviser/sound artist David Toop. Leister’s work focusses on representations of the face and facial expressions, explored in performance here through the manipulation – folding, layering, cutting – of printed photos of Noh masks, conjuring live the multitude of human expressions through fixed images. Leister, accompanied by flute improvisations and electronics by Toop and Isso, narrated through fixed faces the gradual transformation of a young woman into a hannya, a demon of rage, jealousy and sorrow. Toop and Leister captured something essential of Noh in their work, though through a firmly European musical aesthetic: the communication of narrative through abstraction and the perception of human emotions. It is through the providing space for works like this that Noh Reimagined showed that inspiration or collaboration can mean something other than wholesale adoption of sounds or ideas.

All photos © Shitong Zhang

Published on 8 August 2018

Anna Murray is a composer and writer. Her website is www.annamurraymusic.com.