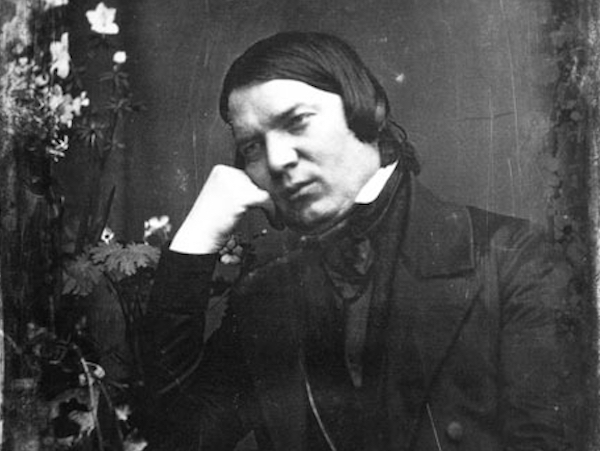

Robert Schumann in an 1850 daguerreotype

The Most Human of Composers

There is a very immediate quality to much of Robert Schumann’s music. His solo piano works, with their inventive titles and often wayward structures, are a testament to his dreams, his loves, his imagination. The songs are laced with the white heat of his many passions – and appear as fresh today as the day they were written. Few composers wore their hearts on their sleeve quite as much as Robert Schumann did; few composers speak so directly to the listener, to the pianist, nearly two centuries later. To play his music is to feel as close as humanly possible to this most human of composers, to his feverish imagination and his febrile loves, to his many ups and (even more) downs.

Schumann – The Faces and the Masks by the American author Judith Chernaik, currently resident in London, is a thoroughly researched new account of the life and music of this composer. Her love for Schumann’s music is unquestionable and a curiosity of the book is that she regularly ‘presses pause’ on the story to describe in some detail the compositions from the relevant period. Thus the musical works are granted the same significance as the biographical facts, not always the case with composer biographies:

Schumann’s three piano sonatas were written during the same years that he was writing sets of variations and creating his own form of piano cycle, from Papillons in 1832 to the major works of 1837–1839, Davidsbündlertänze, Kreisleriana, the Noveletten, Kinderszenen, and Humoreske… All three sonatas show Schumann struggling to express his Romantic nature as the impassioned Florestan and the gentle Eusebius while conforming as best he can to classical sonata form.

To anyone familiar with the broad outlines of Schumann’s life, there are no major surprises in store in The Faces and the Masks. We read about his unremarkable childhood in Zwickau and early romantic escapades, his brief legal studies in Leipzig followed by his decision to renounce law and become a pianist, under the tutelage of Friedrich Wieck. His infatuation with Herr Wieck’s teenage daughter Clara, nine years his junior, is well documented, as is the well-known legal battle he had to fight with her father in order to eventually marry her. His failure to become a concert pianist, his founding and editing of a critical music magazine (the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik), the happy days of their early married years, the outpouring of piano music and song, and Clara’s extensive concert tours are all described in great detail.

The details of Schumann’s attempts to improve his piano-playing did not make easy reading:

When he was living with Wieck, Schumann decided to improve his manual dexterity with an invention of his own, immobilizing the middle fingers on his right hand one at a time so that the neighbouring weak fingers would be strengthened. In his diary he refers to the invention as his ’cigar mechanism’ … Whatever the invention was, it had the unintended consequence of paralyzing his middle fingers…. Eventually all three middle fingers seemed to be paralyzed.

Complicated relationships

The central pages of The Faces and the Masks chart Schumann’s growing family and his establishment as a well-known and highly respected composer. The varied and often complicated relationships with Chopin, Mendelssohn, Joachim and, later, the young Johannes Brahms, are given special attention, as is the central relationship with Clara. We also learn about Schumann’s not always successful forays into stage and oratorio works (Paradise and the Peri, Genoveva and others), while the four symphonies are dealt with in some detail.

It is fascinating to imagine Schumann and Mendelssohn gossiping about Chopin’s weaknesses, and to discover what Chopin thought about Schumann’s literary titles:

[Chopin] was unsympathetic to the high Romanticism that Schumann espoused so enthusiastically. Chopin scorned the very idea of literary titles for music; he believed that music should speak for itself. … Schumann remained happily ignorant of Chopin’s negative views, and he continued to revere Chopin’s works with high praise. … He agreed with Mendelssohn that Chopin’s second subjects in his sonatas tended to be weak. Schumann and Mendelssohn were receptive to everything new and original, but they both believed in the necessity of structure and clear organization.

The book’s narrative also explores later disappointments following the Schumanns’ move to Düsseldorf, where Schumann had a difficult time as Director of Music.

Perhaps the most affecting and moving part of the story, however, is the account of his suicide attempt in 1854:

He had left the house in his dressing gown and slippers, with no coat or hat. Because it was carnival time, no one thought to stop him or to question his light apparel in the February rain. He made his way through the crowds to the ‘bridge of ships‘ across the Rhine, where he gave the toll keeper his silk handkerchief in lieu of coins. He stumbled across, stopped halfway, and threw his wedding ring into the river. Then, before anyone could stop him, he plunged into the river himself.

His swift rescue by boatmen was followed by his committal to a mental institution in Endenich, near Bonn, where he died in 1856 of general paralysis, thought to be connected to the contraction of syphilis some two decades earlier.

Florestan and Eusebius

There is a lot of emphasis on Schumann’s particularly fecund imagination and especially on the two opposing characters he invented in his own mind and which permeate his early piano music – the outgoing Florestan and the more introvert Eusebius. This aspect of Schumann’s character seems to be particularly fascinating to the author and in fact she goes as far as to allude obliquely to them in the title of the book: The Faces and the Masks. Chernaik goes to some trouble to describe how the different extra-musical elements permeate his compositions, including the elaboration of musical themes created from the names of love-interests or place-names, something that clearly appealed to our romantic subject. This aspect of the book is particularly engrossing and convincing.

Schumann – The Faces and the Masks seems to be aimed at a very general audience. In her introduction, the author expresses the quite simple hope that readers will be encouraged ’to listen to his music, the major works above all’, seemingly allowing that many people picking up the book might never have listened to a note of his music. It might be added that the descriptions of the musical works, while excellent and entirely valid, are detailed and in some cases read rather like extensive programme notes for a concert; occasionally seeming to stall the story rather than keeping it moving.

The extent of Chernaik’s research becomes clear early on when she presents fresh evidence regarding the identity of Robert’s teenage girlfriend ‘Christel’ – and continues throughout the narrative until, movingly, we learn of the publication as recently as 2006 of Schumann’s complete medical records from Endenich.

In 1988 the documents came into the possession of the composer Aribert Reimann. After much heart searching, he deposited the sixteen folio sheets, closely written on both sides, in Berlin’s Akademie der Künste. The complete medical record was published in 2006 with all the documents relating to Schumann’s illness, and a full analysis of its origin and progress. The medical diary makes harrowing reading. Schumann’s entire history fed into his delusions….

Two slightly controversial and interrelated side-issues are also decisively put to rest in Chernaik’s book; firstly the eternal question of Clara and Brahms – did they or didn’t they have a sexual relationship (spoiler alert – they didn’t) and secondly the question of why Clara did not visit Robert in the asylum (she was actively discouraged from doing so to avoid upsetting him). However, to describe the book as ‘groundbreaking’, as the jacket’s blurb does, is perhaps slightly overstating the book’s case.

Overall, despite the excellent scholarship, there is something a little dry about this biography. The chapters do not flow from one to the other and we are not itching to move on to the next episode of the story. Perhaps this has to do with the presentation of the descriptions of the musical works with their newspaper-column-style subtitles, or perhaps it is just the pace or style that the author has adopted. Despite this, the book is a welcome addition to the many books about the Romantic genius that was Robert Schumann and can be enjoyed by a very general readership.

Schumann – The Faces and the Masks by Judith Chernaik is published by Knopf. Visit www.knopfdoubleday.com.

Published on 20 March 2019

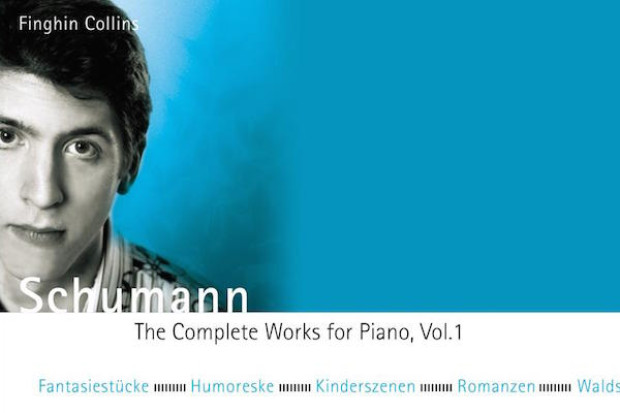

Finghin Collins is an Irish concert pianist with a busy international performing career. Winner of the Clara Haskil Competition in Switzerland in 1999, he has played with many of the world’s finest orchestras and conductors. He is also Artistic Director of Music of Galway (since 2013), and of the New Ross Piano Festival, which he co-founded in 2006. Collins’ extensive recordings of Schumann’s piano works for Swiss label Claves Records in 2006 and 2009 received much critical acclaim, including 'Editor’s Choice' in Gramophone Magazine.