Nua Traditional / Ceol Nua Dúchasach

Over the years Kíla have been called all manner of things, the most undesirable of them being: ‘Acid Ceili’, ‘Thrash Trad’, ‘Celtic Rock’, ‘Tribal Celtic’, ‘Celtic Caribbean’, ‘Celtic Fusion’and the worst of all - ‘Afro Pop Celtic Genre Busters’!

Although this type of classification puts us in the privileged position of being pondered, I would rather if it was the music and not the lack of adequate adjectives that moved them to such verbosity. ‘It’s traditional music, but it’s not’, is the punter’s usual response, and it is with this paradox in mind that I am forced to classify a style of music that can, at anyone time, be and not be.

Take the river as a metaphor: ‘A river is never the same twice’, said the famous philosopher. ‘A river is never the same once’, added his pupil. Let me add that ‘A river is never the same ever’. It is in constant flux. It starts at source and passes through the land until it reaches the great big sea and becomes known as an ocean. A river’s flux, however, is not dependent on source water alone. The geographical features below it will influence it to run slow and smooth, to pick up pace and race along a steep verge, to thrash about as rapids, or to cascade large, long and dramatic as a waterfall. And so it is with traditional music. It was never in an arrested state, it has always been in a state of flux, and it is shaped in much the same way. For geographical features read: technology, amplification, pace of life, performance spaces, instruments, and emotions.

Where Kíla and others like us are coming from is downstream a good bit, and many other water sources have flown into the area that we’re swimming around in. We are inspired not only by the river’s flux, but by the beauty of its surrounding flora and fauna.

Sean Ó Riada, the man who revolutionised traditional Irish music by putting a group of musicians on a classical stage, playing traditional tunes and songs with rehearsed arrangements, and using a harpsichord and bodhrán for backing, once wrote that ‘Irish traditional music is like a river, and new influences are like pebbles that get thrown in and caught up in the flux.’ Paco de Lucia, the famous flamenco guitarist, so upset his elders with his new style that they threatened to oust him from the flamenco fraternity. The recent addition of drums, bass and amplification, etc., forced the conflicting musical ideologies to name themselves. You will now see bands in Spain classified as either Nuevo Flamenco or Flamenco Pura.

Similarly, in Argentina, the tango style created in the brothels of Buenos Aries consisted solely of a guitar, bandoneon (a type of button accordion) and a vocalist. But when a young Argentinian by the name of Astor Piazzola was given a bandoneon instead of his preferred gift – a guitar – the face of tango changed utterly. So much so that he was sent death threats by some of the more fanatical older players. The two styles are now classi fied as either Nuevo Tango or Tango Pura.

Bossa Nova, which means ‘new beat’, recently underwent an imaginative transformation since its creation and rise to popularity in the early sixties. It is now classified as Nova Bossa Nova.

So how does one classify downstream traditional Irish music? Taking inspiration from how the Spanish, Argentinians and Brazilians solved a similar conundrum. I now baptise thee… ‘Nua Traditional’ or ‘Ceol Nua Dúchasach’. Nua means ‘new’ in Irish, and this will also define which country’s tradition the phrase is referring to.

Most countries are happy with two styles, but Ireland, with its triscaline nature, must have three. There are many others of course: ceili bands, ballad bands, paddy-beat pub bands, sean-nós and nua-nós. But it is the traditional three, the three-legged stool, with one foot in the past, one foot in the present and one in the future, that are being referred to below.

Pure Traditional

Seamus Ennis

Patsy Touhey

Tony MacMahon

Noel Hill

Seamus Tansey

Michael Tubridy

Johnny Doran

Martin Hayes

Michael Coleman

John Doherty

Traditional

The Bothy Band

Altan

Dervish

Lúnasa

Danú

De Danann

Planxty

Solas

Lia Luachra

Nomos

Nua Traditional

The Chiefiains

The Horslips

Stockton’s Wing

Moving Hearts

Kíla

Deiseal

Davy Spillane

Sin É

Mícheál Ó Súilleabhain

Cool Finn

The Bothy Band set the guidelines for what we now term traditional music. This is the music you hear at Irish festivals and in pub sessions. They introduced the bouzouki and mixed it with pipes, fiddles, flutes, guitar and clavinet. They played with skill, dexterity and power, their music had a sense of inclusion, and they made it seem like anything was possible. They epitomised the acoustic sound of city living and were the inspiration behind many of today’s musicians learning to play the music, and more importantly, learning to play together.

Another member of the same band, who left due to his feeling that they were too gimmicky, set the guidelines for what is being termed pure traditional musIc. Tony MacMahon decided to champion the cause of the solo musician when he noticed that his instrument was being clouded by the other instruments and his expression being compromised in order to fit in with the group. He has stood resolute like a holy Indian Sadhu might stand in the one position for years while the rest get on with the task of getting on with each other. But he offers a polemic rather than guidance to young musicians and alienates all those who have ‘unpure thoughts’ in relation to the music.

He calls our music ‘mongrel music’ and, despite his excellence on his instrument, he is the worst, or best (depending on your point of view), spokesman for this particular style of expression.

Moving Hearts consolidated the new and until now unnamed movement Nua Traditional. The Chieftains, with their very defined and refined arrangements, although acoustic, had already been swimming in this area a long time before, and the Horslips with what was being called Celtic Rock were also in this new pool. This was music for the bigger stage and for play-back on disc, it didn’t fit that well in the pub atmosphere nor would it be at home in a thatched cottage in west Clare. But with its emphasis on new songs, new tunes and experimentation, audiences unfamiliar with and uninterested in traditional music came in their droves.

Although many bands and musicians playing today fall under all three different categories and express a tune or a song in either style, there are some bands who are more obviously one than the other.

You can see the pattern forming. Pure Trad is characterised by the solo performance, and when it’s being accompanied it is done sparingly, with Johnny Doran as the exception.

Traditional is characterised by what the Bothy Band got up to in the seventies. Pipes, flutes, fiddles, bouzoukis and guitars, all playing together with fire and passion or what the Spanish would call duende. It is mostly acoustic with spontaneous bursts of rhythm and harmony, and songs are usually sung in English, sometimes by men but mainly by a female singer.

Nua Traditional is characterised by its deliberate arrangements, its recently written tunes, its choice of backing instruments, its blending of musical genres and its multi textural full sonic sound.

None of this classification, of course, precludes that any style is better than the other. The feeling one gets off the music is all that matters and no style has a monopoly on that.

Critics in future should not start critiques with the tired statement ‘The purists wouldn’t like this one. .’. Nua Traditional is a style completely unto itself and should not be assessed with the purist values in mind. It should be adjudicated first on how it makes one feel and secondly on its capacity to reach the aspirations to which it is trying to attain.

So a style is named; let it remain and, if a particular style evolves from this flowering let it also be named. But let it be that Nua Trad remains the title of traditional music that continues to search for new ways to express itself.

–

First published in JMI: The Journal of Music in Ireland, Vol. 1 No. 3 (March–April 2001), pp. 10–12.

Published on 1 March 2001

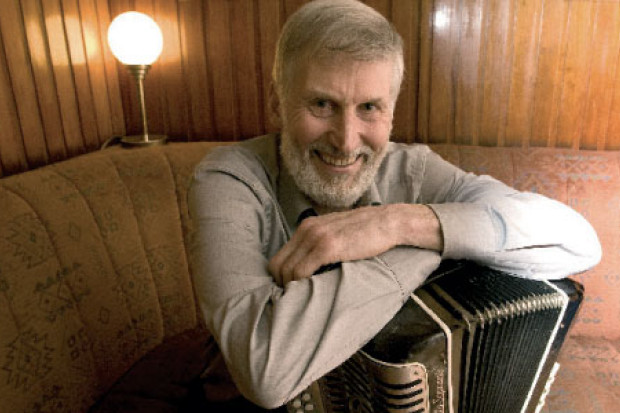

Rossa Ó Snodaigh plays percussion and whistles with Kíla.