Opening Up Hidden Fermanagh

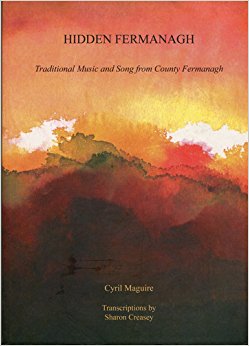

In 2001 Cathal McConnell mentioned to fellow Fermanagh flute player Cyril Maguire that it would be a great thing to ‘put together a CD of Fermanagh music’. The idea lodged in Maguire’s head and to it he applied his considerable academic energy and knowledge of local fiddlers, flute players, accordionists and singers. The areas he knew best were in the vicinity of Derrylin and Derrygonnelly, and his contacts there together with locally accessible information became the germ which produced this wonderful CD and tune and story book, Hidden Fermanagh.

Core material in this text is anecdotal stories of the county’s numerous musicians, many of them inter-related. But the music centre to it all is of the nineteenth-century collection of music and music lore known as The Gunn Book, compiled in crisp copperplate pen and ink by one John Gunn. Reputed to be ‘something of a dandy’ – he dressed in ‘a stovepipe hat … green coat with tails … Coloured waistcoat … britches … stockings’ – his collection survived in respectful hands. Its collected one hundred and seventy-eight tunes were inserted in a hand-bound book according to a plan – hornpipes first, then jigs, then reels (the standard nineteenth-century format) with some later additions including a couple of Moore’s ‘melodies’. This collection had followed close on Edward Bunting’s heels (1840), it overlapped with Petrie’s Ancient Music of Ireland (1855) and pre-dates P. W. Joyce (1873) and O’Neill (1913). It takes in the end of the harpers and the rise of the travelling fiddler, and the new fashion of ‘writing down’ dance tunes which possibly in Ireland had no relevance until the harpers were gone and fiddlers and pipers mushroomed to service the fashionable demand for dance repertoire.

Reasoned deduction is a casual, but key, part of Hidden Fermanagh: ‘You get the feeling that the old school of harpers … had no great regard for dance tunes’, ‘The collection would appear to have a Scottish influence …’, ‘What is surprising, is the number of little-known tunes’, and so on. The author’s conclusions about the inclusion of eleven Jackson tunes (from the later 1700s) has interesting implications for the debate over whether it was the Limerick Jackson or the Monaghan one who composed them. For if the included ‘Jackson’s Dream’ and ‘Jackson’s Mistake’ were popular in Fermanagh it is more likely that they were of Ulster rather than Munster. Directing the deductions is the fact that though not published, The Gunn Book did however colour and police the local lineage of players’ repertoires – as seen by the popular currency of some of its tunes, including ‘Primrose Lass’, ‘Priest in His Boots’ and ‘Collegians of Glasgow’. What of the Scottish connection? Many of these tunes were reputed to have come from a travelling fiddler named ‘Celter’ – no origin given for his name (maybe to do with ‘kilt’?) – including ‘Ereshire Lasses’, ‘Miss Huntly’s’ and ‘Miss Hamilton’s’, clearly Scottish, while tunes such as ‘Sprig of Stradone’ and ‘Humours of Mackin’ were local and Irish. Celter’s tunes have ‘an awful Donegal tendency’, says John McManus, who hears them as similar in style to those of Johnny Doherty.

But though The Gunn Book is the centerpiece in Hidden Fermanagh, much local anecdote and yarning illuminates its social and economic niche, in particular, interviews with John McManus and his memories of fiddling with the Assaroe céilí band and ‘crossing over’ to waltzes, one-steps and samba on a saxophone that he learnt from big-band players on the radio and played with the Starlight Dance Band. The old bogey of the priests stamping down on the latter as the ‘music of sin’ was well aired in Fermanagh too, a yarn here of the priest calling a decade of the rosary from the stage in the middle of a dance to compensate for a tango that the band had just got away with. But nothing stopped, and dancing continued with McManus moving on to the Carnegie Showband which used the forty days of lent to make itself ready for the dance-trail by the time Easter came to swing the Silver Sandal ballroom: McManus and company once opened for Larry Cunningham’s Mighty Avons. The place of pop song side by side with the traditional is vivid in these interviews – some songs were learnt over the phone from a relative who was in the women’s military in England, and ended up on the local stage. The spaces for each music form appear to have remained non-contentious: ‘… after the dance would be all over … four or five of them would … have a bit of a session until three or four o’clock in the morning’. Sight-reading sat side by side with this orality in instruction for the music of political agitation – flute band rehearsals involved notes scripted on a blackboard at the AOH hall in Derrylin. There are tales of local artistic intelligences at work too, for instance William Carroll of Drumbeggan and his reputation as a flute player – fastidious about his tone he would ‘sound’ different positions in a room in order to locate the space’s sonic focus, to harness for his advantage the natural acoustic of the space.

Hidden Fermanagh is an impressive work of locally-focused ethnomusicology which locates key past and contemporary figures in Irish music. It illuminates their lives by jigsaw building and historical ethnography, and sets them in a family tree which makes visible hugely-interesting connections in music-making today. Most vivid among this are the memories of Cathal McConnell – his reminiscences about flute players Felix McGarvey and Eddie Duffy, the Gunns and Mick Hoy. Song transfuses the melodic tapestry, some of it from local poets such as the early nineteenth-century Peter Magennis who celebrated the plain people of his locale in the joys and trials of whisky making, agricultural practices and pastimes. Song transcriptions are of the place and from the mouths of locals: Annie McKenzie’s ‘Frog’s Wedding’ (collected too in the Appalachians, in Scotland and England), Willie McElroy’s ‘The Hiring Fair’, Gabriel McArdle’s ‘Bessie the Beauty of Rossinure Hill’. Sharon Creasey has transcribed the Gunn tunes in a hundred pages or so, and the author’s notes to these are quite amazing for not only giving each one local provenance, but tracing the history of their printed forms too, often back a couple of centuries. Thirty-four song words and music transcriptions round up this terrific publication, and many of them and the tunes are performed on an accompanying CD.

Hidden Fermanagh, published by The Fermanagh Traditional Music Society at Drumbeggan, Monea, Co. Fermanagh. Price £12 sterling; CD £12.

Published on 1 July 2004

Fintan Vallely lectures in traditional music at Dundalk Institute of Technology. He is author of several biographical and ethnographic books on the music, and is editor of the A-Z reference work Companion to Irish Traditional Music.