Vocal Musics of the Past

The eerie laments sung on the decease and burial of individuals attracted the attention of many travellers in Ireland over the centuries who left multiple accounts of the practice, but precious little in the way of musical or verbal transcriptions. For these, and much more, we are heavily indebted to George Petrie, Eugene O’Curry and their coterie. Keening for the dead (caointe) served to aid the spirit in making its transition from the world of the living to the regions of the dead and to provide keener and listener with emotional release during a difficult rite of passage. Whereas elegies (marbhna) used strict poetical parameters, the keen could be (and frequently was) extemporised.

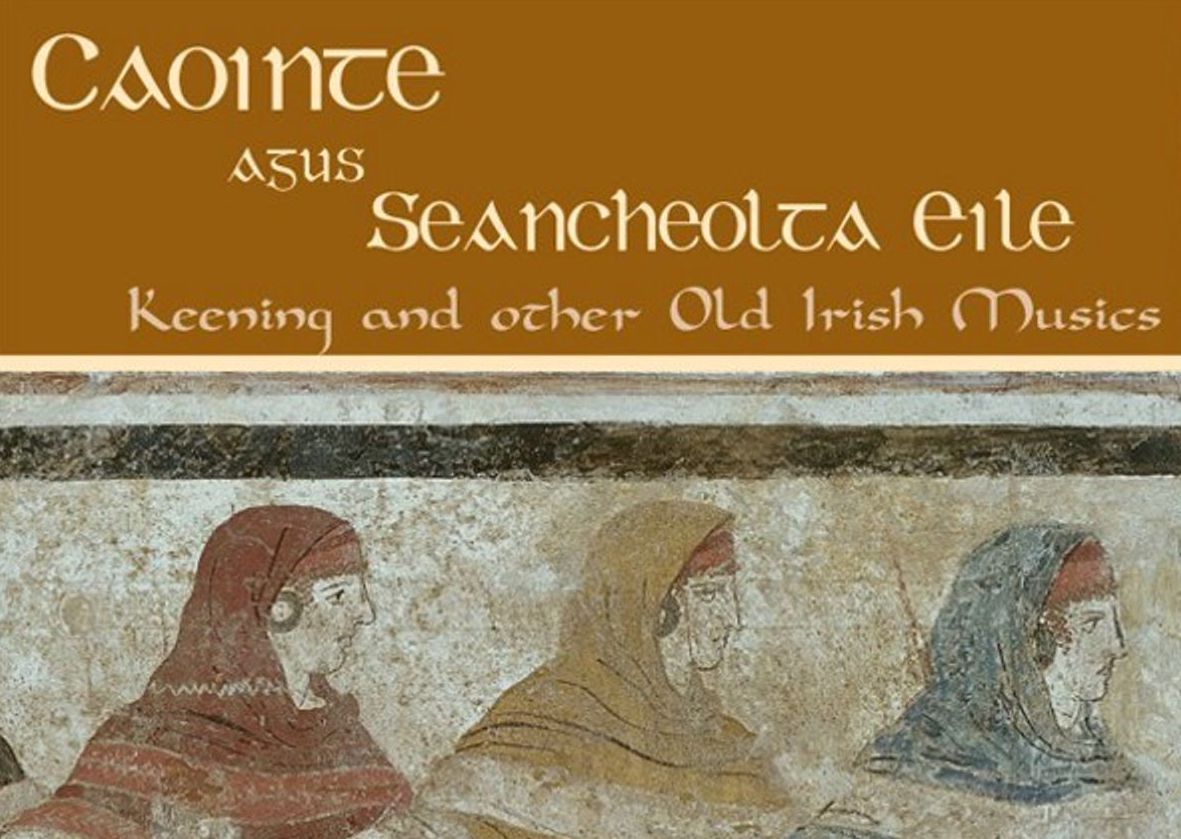

Those who have heard Professor Breandán Ó Madagáin speak on the subject of keening and older Irish (vocal) music will be aware of an enthusiasm and proselytising passion he has had for the subject for many decades now and will not be surprised at the erudition which is packed into the pages of his new book, Caointe agus Seancheolta Eile: Keening and other Old Irish Musics.

The author points out (with Dineen) that death was not the only time for keening; it would be used on other occasions of grieving also. He cites a keen on blighted potatoes and one sung by a mother on the occasion of her children emigrating to the United States. Indeed, this writer is reminded of the late Mullagh fiddle player, Junior Crehan, who told me of times he had been at Miltown Malbay train station with a crowd who had conveyed intending emigrants there following the night-long American Wake. When, about a half mile out, the West Clare train sounded its whistle, this was the signal for prolonged wailing from the women on the platform which did not cease until the train had receded from sight.

The chant-like music for the keen, like the words, would be extemporised, but that of the religious songs (amhráin bheannaithe) and lays (laoithe) could have a remarkable stability to the extent that Eugene O’Curry’s father, Eoghan Mór Ó Comhraí, insisted that all lays were sung to a single air, that of ‘Sciathlúireach Mhuire’ (‘Mary’s Breastplate’).

Another strong area with Ó Madagáin in this book is his interest in work songs (amhráin oibre), an area of considerable neglect in Irish tradition and one wherein it is most likely now too late to do very much; certainly as far as fieldwork goes. He posits (with Petrie) that ‘the awful unwonted silence’ which followed the Famine took the heart and the desire to sing out of the people. Undoubtedly this was a factor in the demise of the work song, but other elements such as the flight from the land, emigration and slowly encroaching mechanisation, which reduced the necessity of collective labour, also contributed to this erosion. He states: ‘Although only a small number of work songs have come down to us, that is not to say that they did not figure largely in the daily lives of the people. The reality was that their widespread practice had declined before collectors realized the worthwhileness of recording them.’ (p. 95) Amen to that. It is also likely that because of their very ordinariness in everyday life and their extemporary nature that collectors did not frequently concern themselves with them as they considered them to be transitory. And they were right.

An aspect of the analysis of the songs which may cause unease to some readers is the interpretation of vocables – meaningless words, usually used in refrain or chorus – as ‘echoing the magic origin of work songs’, that is, as magical incantations whose meaning has been lost. Ó Madagáin’s opinions are not to be dismissed lightly, but in this case there may be a danger of over-kenning, even though he allows that it is not possible to make a more positive deduction than to say that these songs ‘seem to echo superstitious practices’. He gives as an example the extremely well known ‘Ding, Dong, Didilum’ (An Táillúir Áerach), but anyone who has ever struck a hammer on an anvil will know that ‘Ding, Dong, Didilum’ (or ‘Dedero’) echoes precisely the sound made by the bouncing hammer.

Since Seán Ó Tuama’s An Grá in Amhráin na nDaoine we have become familiar with the French influence on Irish song. Refreshingly Ó Madagáin also allows for the influence of English song. This ‘is not to say that the Irish did not make their own of this kind of European music, but they retained the basic structure in their own compositions, very different from the putatively earlier native music’.

Religious songs, political songs, macaronic songs and several other genres are also covered and examples supplied on the CD where they are sung by the author. There is so much that Professor Ó Madagáin has written on Irish music over the years which is spread over a long list of arcane or out-of-date journals that it is high time they were collected and published in a single volume which would be of immense value to Irish song scholarship. In the meantime add Caointe agus Seancheolta Eile to your bookshelves, not only is it informative and very readable, it is extremely good value.

Breandán Ó Madagáin, Caointe agus Seancheolta Eile: Keening and other Old Irish Musics

Cló Iar-Chonnachta, 2005. 156pp with CD of examples sung by the author, ISBN 1 902420 97 7, pb €16

Published on 1 May 2006

Tom Munnelly (1944-2007), born in Dublin but resident in Miltown Malbay, Co Clare, since 1978, made the largest field-collection of Irish traditional song ever compiled by any individual. After recording privately in the 1960s, and collecting especially from Traveller singers, he became a professional folklore collector and archivist with the Department of Irish Folklore, University College Dublin (now the UCD Delargy Centre for Irish Folklore and the National Folklore Collection), from 1974 to date, with a concentration on English-language song. He lectured and taught widely, was a leading activist in many folk music organisations and festivals, including the Folk Music Society of Ireland, the Willie Clancy Summer School and the Clare Festival of Traditional Singing, and he served on national bodies such as the Arts Council. He was the founding Chairman of the Irish Traditional Music Archive from 1987 to 1993. Recently he was presented with the festschrift Dear Far-Voiced Veteran: Essays in Honour of Tom Munnelly, and was made an honorary Doctor of Literature by the National University of Ireland Galway.