Whither the professional traditional musician?

Why We Need a Traditional Music Infrastructure

In 2012, when we launched a listings service on The Journal of Music, it was in an effort to capture what was happening musically, as in concerts, festivals and other performances. There are not enough writers and editors in the world to track the range of activity in contemporary music life, but using the internet and enabling readers to contribute suddenly presented that opportunity. The key was creating a listings service that was flexible enough to accommodate a huge range of styles, but organised enough to make sense of it all.

The picture of music that these listings present continues to surprise. One trend that I’ve noticed is the rise in classical music activity in Ireland and the contraction of traditional music. This is counter to the general impression of Irish musical life, so what is happening?

Eleven years ago, when Irish traditional music’s profile was at an all-time high, and the Arts Council was forced to start properly funding it, the Special Committee on the Traditional Arts wrote:

Regardless of the present relatively buoyant situation, the Arts Council must seriously consider what the future for the traditional arts is on its present trajectory. Although it is true that these arts are presently enjoying a period of increased activity and a new degree of popularity, were they to subsequently experience a ‘dry stretch’, with no prior efforts to firm up the support structures for these art forms, even a slight decline in their fortunes would do serious damage to the traditional arts.

It is difficult to conceive of a ‘dry stretch’ in traditional music, when there are so many tens of thousands of people worldwide playing it, but what is too often misunderstood is that this kind of popularity, and these kind of numbers, means that the art form needs more investment, not less. There are, for example, a growing number of artists who make their living from traditional music, and their work relies – like every other professional artist in every other genre – on there being a constantly developing music infrastructure: organisations, venues and institutions who can provide funding, commissions, performance opportunities and employment that allow them build a career. But is that infrastructure there?

Arts Council funding is basically divided into the large annual grants for resource organisations, which they generally support on a continual basis; funding for local authorities and venues; and lots of small grants for temporary project activity. In 2004, when the Special Committee issued their report, the main Irish traditional music organisations received direct funding of €0.89 million from the Arts Council. In 2015, that figure had increased to €1.15 million. Classical music organisations received €4.5 million.

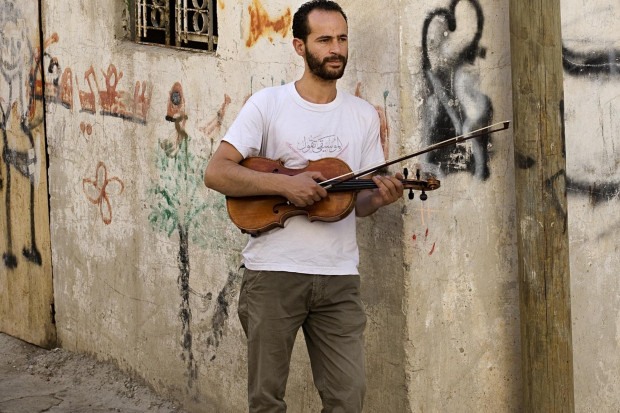

This difference perhaps explains why the world of the professional traditional musician seems to be contracting, and why classical music appears more prominent. The infrastructure that traditional musicians require is simply not keeping pace. Faced with this, outstanding musicians naturally choose other careers, and never realise their professional music potential.

This is not to suggest that classical music is that easier a career choice. Ireland’s music infrastructure is seriously underdeveloped. Further evidence of this can be seen in the Jobs & Opportunities section of the The Journal of Music listings. Throwing up a constant flow of employment and funding possibilities, it has laid bare the extent of the musical infrastructure in Ireland and the UK – and how they compare.

The range and number of opportunities available in the music sector in England is impressive, but that is to be expected given a population of 53 million. In comparison, there is but a trickle of music jobs from the Republic of Ireland, Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales.

Watching these listings, a clear picture appears of the opportunities available, and what – if you are planning a career in music and want the quickest route to financial security – you should be doing.

There are two main options: study classical music and don’t stop until you have a PhD and can lecture in it (probably in England), or make sure to obtain business qualifications and experience to add to your music skills, and slide over into the administrative side in well-established institutions. If you specialise in any other genre aside from classical music, or live anywhere else, you have reduced your chances of financial security.

This means that the situation as regards musical infrastructure, certainly in Ireland, is perilous. It simply isn’t developed enough to support all the music graduates and musicians that Ireland is producing.

The traffic to the jobs and opportunities page on The Journal of Music indicates something else too, that despite their bohemian image, financial security is very important to musicians and composers.

Is there an understanding and awareness of this at the highest level? Those who have influence over the funding and potential development of Ireland’s music infrastructure could profitably spend a week watching these listings. When one sees the intensity of activity, and how modest our music infrastructure is in comparison, one can fully appreciate the challenge that musicians face.

Published on 7 July 2015

Toner Quinn is Editor of the Journal of Music. His new book, What Ireland Can Teach the World About Music, is available here. Toner will be giving a lecture exploring some of the ideas in the book on Saturday 11 May 2024 at 3pm at Farmleigh House in Dublin. For booking, visit https://bit.ly/3x2yCL8.