Letters: The Meaning of Minimalism

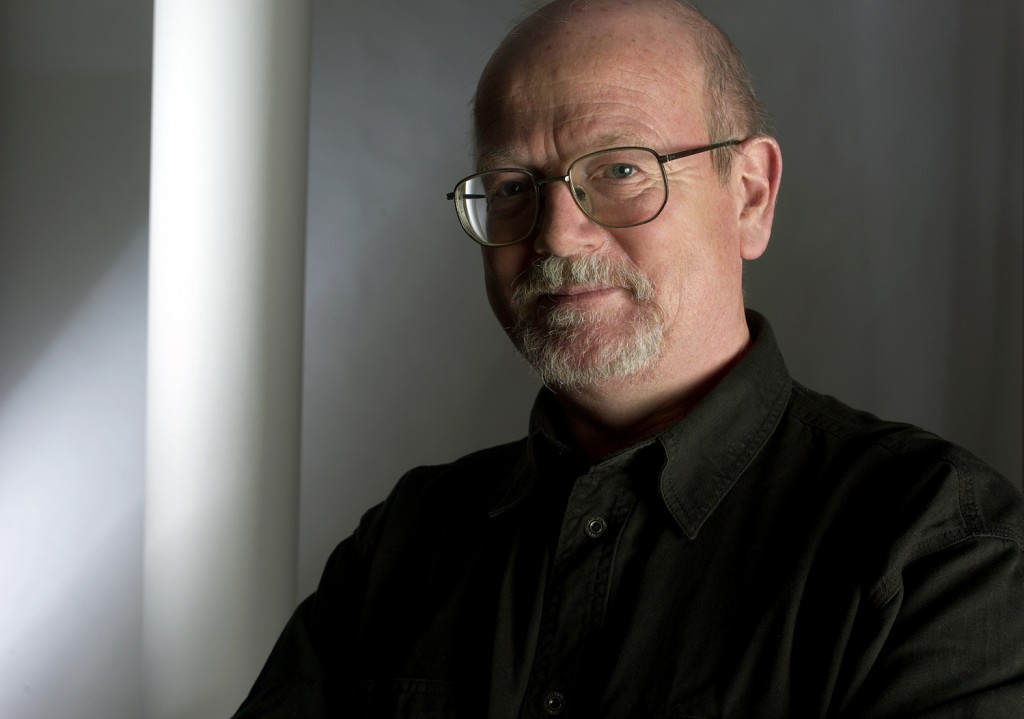

Eric Sweeney, Waterford, writes:

John McLachlan’s article on the future of minimalism (‘The Life of Riley’, July–Aug 2007) raises a number of interesting points and the time is surely ripe to assess what Steve Martland has provocatively called the main, if not the only, important development in musical style since the 1960s. The term minimalism, as John McLachlan correctly points out, has become outmoded as a means of stylistic definition and if we think of composers as diverse as John Adams, Arvo Pärt, Michael Nyman and John Tavener it is difficult to see what, if any, shared language their music illustrates. It’s perhaps easier to describe what their music does not express in that they have turned their collective backs on atonality, serial technique and aleatoric procedures. Indeed the term minimalism has really become meaningless unless as a definition of an historic style which emerged in the USA in the 60s and whose ideas were to influence the next generation of composers in widely different ways. Whatever our views of it, it was the first style to challenge what Tavener delightfully called ‘the po-faced serialists’ and their Darmstadt-led dictates about what should or should not be regarded as proper music. For this we should be grateful and, as a teacher of composition, it is refreshing to see the present generation of young composers expressing themselves with a freedom and confidence which was sorely lacking in previous decades. No longer is there any sense of young composers having to be on their best behaviour and looking anxiously over their shoulders for peer approval.

Reich’s poetically phrased vision that ‘in the future composers will be free to play in the garden of all that has gone before’ perfectly describes this new sense of liberation from the dour orthodoxies of Darmstadt and their self-perpetuating elitist view of the musical world. The irony is that the modernists who once led the brave new world of experimentation and exploration have themselves become the conservatives desperately trying to defend a rapidly diminishing artistic position, and their shrill protests that ‘surely music cannot be any good if so many people like it’ falls increasingly on deaf ears. The success of the last two RTÉ Living Music festivals is proof that, contrary to what we were always told, there is an audience for new music and, while they may not be the normal classical music buffs who attend the National Concert Hall on a regular basis, they have a healthy curiosity about what is new and their informed musical tastes may range from experimental rock through free improvisation to whatever you are having yourself. Their presence and involvement in the new music scene is surely a cause for celebration.

Interestingly, minimalist music is far from easy to write and eager composers with their fingers poised on the Copy/Paste commands of Finale or Sibelius will find it is a technique which makes surprising demands. Yes, of course it’s easy to produce limitless streams of musical sounds at the touch of a button, but to make musical sense, to create pieces which are well structured, to engage and to sustain the listener’s interest is as difficult, if not more difficult than ever.

Minimalism is no easy cop-out and demands a rigorous command of the composer’s self-limited material as well as a radically different approach from the listener who must be prepared to delve below the surface of seemingly similar patterns of sound to find out what really is going on. The importance of minimalism is that it has radically altered the way we create, assess and listen to music as well as the fact that it has pointed to a new liberating way forward for so many composers who had found themselves in a creative cul-de-sac. If we think of Louis Andriessen’s persuasive amalgamation of Stravinskian rhythms and Reichian textures it is but one of the many ways minimalism has opened the doors to a new and highly personal language.

It seems clear to me that minimalism would not, and could not, have come about without the radical redefinition of music by Cage and La Monte Young in the 50s and 60s. Their fundamental re-examination of everything we take for granted about music cleared away decades if not centuries of casual assumptions and made us look with new eyes at the raw essentials of sound. What is clear now is that music in our post-modernist world can be created from whatever elements the composer wishes and that it is the healthier and more genuine for that.

Published on 1 September 2007

Eric Sweeney (1948–2020) was a composer, conductor and organist, and Head of Music at Waterford Institute of Technology between 1981 and 2010. For a full obituary see here: https://journalofmusic.com/news/rip-composer-eric-sweeney