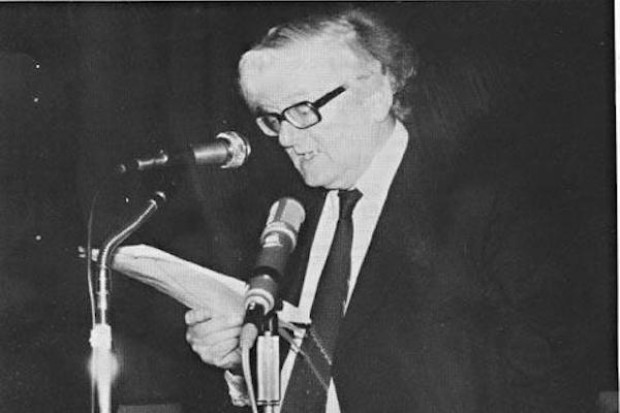

Joe Burke at the Willie Clancy Summer School in 2003 (Photo: Tony Kearns, courtesy of the Irish Traditional Music Archive)

'We have lost the most loved musician' – Remembering Joe Burke (1939–2021)

The accordion player Joe Burke, who made a number of seminal recordings in the 1960s and 70s and had a significant impact on Irish traditional music over several decades, has died (20 February) aged 81.

Burke was born in Kilnadeema in 1939, south of the town of Loughrea in east Galway, and grew up in a vibrant musical area with musicians such as his uncle Pat Burke and the Downey brothers in the locality. In 1959 and 1960 he won senior accordion titles at the Fleadh Cheoil and recorded some of the last 78s to be made on the Gael Linn label. He subsequently moved to America in the 1960s and performed with fiddle-players such as Andy McGann, Paddy Killoran and Lad O’Beirne. He also won the Fleadh Cheoil duet competition with fiddle-player Aggie Whyte in 1962.

A link between generations

Burke, who also played flute, whistle and fiddle, was deeply influenced by the Irish traditional music recorded in the first half of the twentieth century in America, particularly the recordings of Michael Coleman and Patsy Touhey, and he became very knowledgeable about that period as well as amassing a large personal collection of recordings and other materials that is now in NUI Galway. Most recently, previously unheard recordings of Coleman that were in his possession were made public by the Irish Traditional Music Archive. In a number of ways, the Galway musician acted as a link between that earlier period and later generations.

In 1966, Burke made the influential album A Tribute to Michael Coleman with fiddle-player Andy McGann and Felix Dolan on piano. This was followed, in Ireland, by a duet recording with the famous fiddle-player Seán McGuire in 1971. Burke and McGuire were a popular performing duet in Ireland and Scotland. Burke’s celebrated solo recording, Galway’s Own, was released the same year.

At the same time, Burke won a televised competition for traditional musicians on RTÉ television, in which he was accompanied by Charlie Lennon on piano. The pair subsequently went on to make another significant recording, Traditional Music of Ireland, in 1973, regarded as perhaps Burke’s finest solo album.

He returned to the USA in 1988 and had a residency at John D. McGurk’s bar in St Louis, Missouri, as well as a radio show on local station KDHX, before returning to Ireland permanently in 1992. In 1997, he received the AIB Traditional Music Award, the forerunner of the TG4 Gradam Ceoil. Burke taught at a number of traditional music summer schools as well as teaching privately in Galway.

Musical following

Burke played a pivotal role in the rise of the popularity of the button accordion in Irish traditional music. At the height of his career, he inspired great devotion from music listeners and had a significant following whenever he played.

‘We have lost the most loved musician,’ said fiddle-player Frankie Gavin, speaking to the Journal of Music this week. ‘When you were in Joe’s company you were in the company of somebody extraordinary.’

Gavin was a teenager when he first met Burke and they did their first concert together in Teach Furbo in Galway in 1973, having met at Joe Cooley’s funeral the previous day and Burke asked Gavin to perform with him. They remained close friends over almost five decades and Burke featured in the ’Sé Mo Laoch programme on Gavin on TG4 in 2018.

He was a real mentor for me. He was always advising me who to listen to. If it wasn’t Michael Coleman, it was Lad O’Beirne. If it wasn’t Lad O’Beirne it was [James] Morrison… He would say to me, ‘Listen to the rhythm’ – that’s the secret of the music itself.

Gavin describes Burke’s music as ‘hypnotic’.

There was a certain hypnosis attached to his music. There was a rhythm that he would kick into. He could play the same tune ten times and you wouldn’t get tired of it, and it would get nicer and more enjoyable each time. It became like a kind of a heartbeat.

Frankie Gavin and Joe Burke during the recording of ‘Sé Mo Laoch for TG4 (Photo: Dónal O’Connor)

No one better at reading an audience

Harper Máire Ní Chathasaigh performed many concerts with Burke in the early 1980s in Ireland and the USA and recorded with him on his album of flute music, The Tailor’s Choice, in 1983. At a time when harp-playing was not as popular in Ireland, Burke’s encouragement was significant.

‘Touring in Ireland with him was an amazing experience,’ she recalls. ‘He was probably the biggest star in Irish music at the time.’

He inspired a kind of fanatical devotion that was unique in my experience … People followed him around. … He was an amazing performer as well. There was nobody better than Joe at reading an audience. … He had a beautiful, lyrical, elegant, always interesting way of playing… he was revered for that but he was loved for his wit… I’ve never seen in traditional music anybody more loved than he was.

Her sets with Burke on The Tailor’s Choice were recorded in one take, and she is particularly fond of the airs he played on the album. She remembers that Burke said his album with Seán McGuire was recorded in the same way.

That’s what all the players of that generation did. It was one take and that was it. They felt that you would lose the moment if you started doing more than that.

It caused quite a stir

Fiddle-player, composer and pianist Charlie Lennon recorded three albums with Burke over four decades, beginning with Traditional Music of Ireland, then The Bucks of Oranmore in 1996 and The Morning Mist in 2002. (‘The Morning Mist’ is also a reel written by Burke.)

Lennon can recall the impact of their first album together. ‘It caused quite a stir when it came out’, he told the Journal of Music. The two had first met in the 1960s in Séamus Connolly’s house in Killaloe and performed together on many occasions in subsequent years. He describes Burke’s playing as ‘electric’ and ‘deadly, absolutely deadly,’ and says Burke was even better live than in his recordings. He recalls concerts with Burke in Rossinver, Co. Leitrim, and Galway where there was a huge reaction from audiences.

In 1984, Lennon wrote the popular tune ‘Planxty Joe Burke’. It was only when Burke’s students started approaching him about it that the Galway musician heard about it.

The two also feature in a famous photo taken in 1981 at the Listowel Fleadh. It shows Burke in a pub session with Lennon, surrounded by a listening audience. The photo featured in Jill Freedman’s 1987 book A Time That Was – Irish Moments and subsequently began to appear in large, framed versions in Irish bars across America.

You don’t just play music for life – music becomes your life

Daithí Gormley was a pupil of Burke for five years from 2004 to 2009 and they remained good friends afterwards. Gormley had first taken Burke’s accordion class when he was 11 at the Joe Mooney Summer School in Drumshanbo, and, although he lived in Sligo and Burke in Galway, he subsequently rang Burke and asked him could he attend lessons with him. Burke had no space but rang Gormley a month later and took him on. Gormley travelled to Galway every second Saturday over five years for lessons.

He says that Burke’s innovation was to bring the nuances of traditional fiddle-playing into accordion playing: ‘He played the accordion like a fiddle. He was the first person to really take that approach and that was revolutionary… he took what people like Paddy O’Brien had done in the 1950s and took it to a whole new level.’

Gormley describes Traditional Music of Ireland as one of his favourite albums.

That was a revolutionary recording. At that stage he’d really developed. A Tribute to Michael Coleman was a great album that he made with Andy McGann and Felix Dolan in 1966, but by 1973 he was a different player again. He had really risen the bar.

‘He taught me much much more than tunes’, Gormley (who is related to Sligo fiddle-player James Morrison through his grandfather), says about his lessons with Burke.

He taught me about the music, the history, the people, the places. I always say that the most important lesson Joe Burke ever taught me was how to listen to music. He taught me how to immerse myself not just in the music but in the era when the music was first recorded. I remember one time he played a reel-to-reel and it was Lad O’Beirne on it, and I said, ‘That’s a lovely tune,’ and he said, ‘Don’t mind the tune Daithí, listen to the rhythm, that’s the important part.’ And I really took that on board.

Burke would say to Gormley, ‘You don’t just play music for life. Music becomes your life.’

Joe Burke’s mass will be streamed online on Wednesday 24 February at 1.30pm.

He is survived by his wife Anne, sister Mary and extended family.