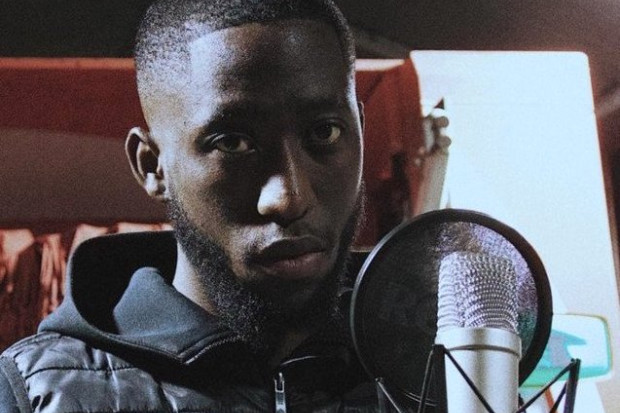

David Keenan (Photo: Eli Penya).

David Keenan's Sense of Place

The first time I saw David Keenan perform, I was about fifteen or sixteen, around the same age as he was. It was at an all-ages gig in the function room at the back of the bowling alley in Dundalk in 2009. With low ceilings, pine-panelled walls, and teens desperately trying to dress like adults while sneaking in bottles of Dunnes-brand vodka or Frosty Jack’s cider (a border-town delicacy), the Sportsbowl was in fact a hub for local music talent. Not the most striking of settings, but perhaps more inspiring than we thought.

There was a culture of gigs for young people in Dundalk at the time. Spaces like the Sportsbowl, function rooms in pubs, and, most importantly, local venue the Spirit Store, were claimed by the youth of the town every few weeks for afternoons and evenings with line-ups drawn from local bands. These gigs were organised by teens and early twenty-somethings and the crowd and musicians were the same age. We had our own thriving community. Friends from other towns went to teenage discos. We put on our own gigs.

The scene in Dundalk grew. Bands formed and some played for years – such as indie band Third Smoke who only stopped playing together last year – while others got their start as performers, including musicians from noise-rock band Just Mustard who recently signed to Partisan Records, and folk singers The Mary Wallopers and their alternative hip hop act TPM. Others from the time are now signed to local indie label Pizza Pizza Records, such as We, the Oceanographers and three-piece Larry, while electro-pop artist AE Mak and singer-songwriter Elephant were also involved in this period.

It was during this time that Keenan wrote the song that brought him to wider attention, ‘El Paso’, a love song to his hometown Dundalk. It became known around the gig circles and crowds would request it – ‘Let’s go back, take me back, to El Paso’ – regardless of whatever band he was playing with at the time. When we were old enough, the gigs moved from the under-age venues to nights at the Spirit Store, or McManus’ bar. The same faces played, but the musicians got support slots with bigger acts, or played as part of local music events and festivals, including Vantastival, which started in 2010.

In 2015, when a video of Keenan singing ‘El Paso’ in the passenger seat of a taxi after a night out went viral, I was thrust back to my teenage years. Suddenly, the whole country was talking about Keenan and ‘El Paso’, not just Dundalk anymore.

He shortly began releasing music, and with ‘The Friary’ I visualised the old church I used to pass on my way to school. When he sang about the ‘Same fella’, went to school in the Della’, I thought of the boys’ school next door to the girls’ school I attended; friends who went there; the colour of the uniform; the spot our bus used to stop at outside the school gates.

A generation before us had Jinx Lennon, who sang about Dundalk and the surrounding border lands in a working-class, relatable voice and in his Dundalk accent, charmed by its extended, flattened vowels and a resonance that’s not-quite-Northern (although outsiders perceive it that way). Over the past six years, Keenan has also captured this spirit. He has toured the world, but it’s his sense of place and the honesty in his songwriting that still is the main draw, epitomised by his extraordinary candle-carrying performance of ‘Evidence of Living’ on Other Voices.

What then, what then?

Keenan’s recently released second album “WHAT THEN?” was written during an artist residency at the Centre Culturel Irlandais in Paris last year, during which he also wrote a book of poetry. The instrumentation is fuller on this record than his 2020 album debut A Beginner’s Guide to Bravery, with more electric guitar and layers of percussion, but Keenan’s role as the storyteller with the local accent remains. We hear tales of travel and experience – seemingly from a soul-searching, raucous time in Paris – embedded in notes of nostalgia and echoes of Keenan’s working-class upbringing.

The record opens with ‘What Then Cried Jo Soap’ and it’s apparent that Keenan himself is the protagonist Jo Soap, setting the tone of self-reflection and exploration for the rest of the album. ‘What can I do you for, let me take your order / Law and disorder on the border in the rain’, he sings over a bell-like percussion that rings over moody, drawn-out strings, seemingly referring to his home place.

Rolling, ricocheting rhythms feature on other tracks – ‘Bark’, ‘Hopeful Dystopia’ and ‘Peter O’Toole’s Drinking Stories’ – while tracks like ‘The Grave of Johnny Filth’ and ‘The Boarding House’ play like ballads and soliloquies. Along with his rounded-around-the-edges, softly spoken Dundalk accent, the poetic, lush style of lyricism which Keenan is known for is a constant throughout.

For me, however, the highlight is ‘Philomena’, written about Keenan’s grandmother, yearning for a sense of maternal familiarity and protection – ‘Sing me to sleep, can I stay with you during the week / We could feed the wee birds’. The vulnerability in these lines is heart-wrenching, amplified for me by the colloquialisms, how I too might speak to my grandmother or a loved one.

In a video interview produced by the Spirit Store earlier this year, Keenan tells of how the death of his friend and bass-player Gareth Kane forced him to reassess his music and purpose, and gave him a newfound sense of focus. ‘I wised up in a sense, I felt like I grew up’, he says.

I can feel that coming out in the writing, even in my singing. Being brutally honest… I was a support act for so long, for so many years. I was trying to project and do all these vocal roles and you know, it’s all marzipan. Whereas now today… I’m singing for myself… and for the first time in my life, I really, really mean it.

At the end of the video, Keenan sings ‘El Paso’ on the rooftop of the Spirit Store, overlooking Dundalk Bay, and there’s a sense that things have come full circle for the artist. Here he is, performing the song that started it all for him, about the town he is rooted in, at the venue that nurtured his career.

I have sometimes wondered why Dundalk has fostered such a thriving music scene in the last ten years or so. Why has a border town on the hinterlands of Dublin and Belfast produced some of the most prolific names in Irish music today, and maintained a self-nurturing community of musicians, venues, concerts, sessions, record stores, open mic nights and events? It is the hard work of artists and promoters of course, but is it also to do with taking ownership and moving on from the town’s past, Ireland’s ‘El Paso’, fifteen minutes from the border? Has it to do with a generation that grew up in the aftermath of the Good Friday Agreement who then were plunged into a recession in their formative years? Perhaps it’s about living on the edge, the edge of two connected but always different identities. I don’t know, but recent talk of the town’s blossoming music scene is not news to the kids of the Sportsbowl. This explosion of music has been growing, organically and exponentially since the mid 2000s, and Keenan is both a product of and a driver behind it, his art a reminder of the value of singing with a sense of place

“WHAT THEN?” is available on Rubyworks. Visit https://davidkeenan.com and www.rubyworks.com.

Published on 28 October 2021

Shannon McNamee is Assistant Editor of the Journal of Music.