London Contemporary Music Festival 2014.

Music for a Dis-Uniting Kingdom?

Across Europe democracy is in the throes of dynamic change. The results may not be the same – so far in 2015, at opposite corners of the EU, the headline electoral beneficiaries have been Syriza and the Scottish National Party – but there seems to be an underlying belief that people’s views have gone unheeded for too long.

It would be good to think that music is somehow representing this tide of popular energy, this bursting of pent-up frustration. So let’s take the new music scene in the UK as a case study, not just because the United-ness of the Kingdom is less certain than it has been for 100 years, but because the current scene is full of energetic artists, bursting with new ideas.

As in many other parts of Europe and North America there has been a proliferation of what appear to be new ways of performing and listening. Instead of the classical concert format – 70 minutes of music with a half-time break – the unitary event, a continuous, immersive presentation of one sort of sound, is increasingly popular for live music. A recent example is James Dillon’s Stabat Mater for soloists, ensemble and electronics at the 2014 Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival.

But old forms are resurgent too. Musicians may give away their music for free on Soundcloud, yet there is a new wave of listeners happy to buy it on LP as well. New CD labels also continue to appear, with Another Timbre’s recent releases of Laurence Crane, Feldman and Wolff testament to producer Simon Reynell’s discerning taste.

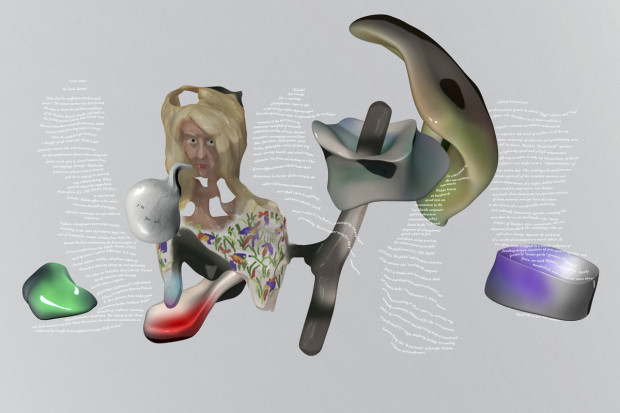

Particularly in London, where classical music venues are either prohibitively expensive to hire or booked out years in advance, new music has had to find new habitats, away from the South Bank and West End. Café OTO, in hipster Dalston, is a favourite, reassuringly full with only about 80 people in the audience. More unlikely has been a multi-storey car park in Peckham, whose upper levels became home to the London Contemporary Music Festival in July 2013. This festival is a moveable feast, its second iteration (including a performance of Michelangelo Pistoletto’s Ten Less One, pictured above) housed in a former carpet factory in Brick Lane. Music promotion as a mobile brand was a model favoured by one of the festival’s curators, cellist Lucy Railton, in the early days of the Kammerklang series, which she founded in 2008 and which continues to this day at Café OTO.

Birmingham City Opera is a similarly itinerant company whose most spectacular recent success was Graham Vick’s 2012 production of Stockhausen’s Mittwoch aus Licht, staging most of the work in a disused chemical works but using the skies above for the ‘Helicopter Quartet’ which forms the most notorious part of the opera.

Birmingham City Opera is relatively well funded and had an extra injection of cash from the 2012 London Olympic Games, but it’s one of the many paradoxes of the current new music scene that while these innovative events have a high profile – both the London Contemporary Music Festival and Mittwoch drew the broadsheet music critics well out of their central London comfort zone and received a lot of very positive press – they are of negligible economic importance; indeed most of Mittwoch’s audience saw the work for free via a live stream of the performance. It is reputations that are being grown here, not bank accounts, and even when there is funding from the Arts Council or the PRS for Music Foundation, it’s a fraction of what goes into the building-based orchestras and opera houses.

Illusions of austerity culture

It might be tempting to succumb to one of the illusions of the austerity culture which the political class has imposed on Europe, that less funding seems to produce more, and more imaginative, art. Of course, there is no paradox, it’s simply that many artists have become their own patrons, subsidising what they want to do with income earned from what they have to do. The days of the career-composer, living entirely from commissions and royalties, are over, certainly for anyone who wants to create anything other than mainstream classical music; performers too take better-paid regular gigs to buy time to play edgier, ill-paid sessions with new ensembles and record labels.

Many musicians also subsidise their work by teaching and one of the not very well-kept secrets is that the universities and conservatoires have become de facto patrons of new music in the UK. Indeed university music departments now employ so many composers, sound artists and performers that they may well be new music’s principal sponsors. As in the USA, however, there is a Faustian pact between musicians and institutions: students learn the techniques they need to become artists but do so in an environment where their teachers’ art is usually referred to as ‘research’, because research is the only non-teaching, non-managerial activity that higher education institutions recognise. Whether these institutions will one day realise that they have bought the souls of several generations of artists, and what retribution they will exact when they do, is uncertain.

In the midst of so much uncertainty, so much marginal, provisional activity, there is at least one organisation whose recent success suggests that not all new work has to live such a hand-to-mouth existence, although it too once flirted with disaster. Sound and Music was created in 2008 out of the merger of a clutch of existing new music organisations — the British Music Information Centre, Contemporary Music Network, Society for the Promotion of New Music and Sonic Arts Network — and the initial merger was one of those quintessentially British cock-ups. Somewhere there was probably an Arts Council document describing the process as ‘a rationalisation of provision’ but there was little rationality in its execution. The result was some way short of the sum of its parts: not so much the sleek new vehicle to deliver excellence, more like a scrapyard jalopy with too many wheels, the accelerator and brake pedals controlled by drivers looking in opposite directions.

A crash was inevitable and duly came in the form of a 48% cut in Arts Council funding in 2011, but in the aftermath of this Dunkirk moment a revitalised organisation, still, it must be said, with a substantial Arts Council grant, has emerged. School-age composers are nurtured through a summer school and then offered further opportunities to develop their work through schemes for college composers, and then as composers in the early part of their professional careers. In just a few years of post-catastrophe Sound and Music, there’s already a sense of fresh voices — Georgia Rodgers, Egidija Medekšaitė, to cite just two — getting time and space within these workshop and residency schemes to emerge into maturity.

It would be convenient if the new music that is emerging conformed to a single tendency, enabling a simple read-off between music and the spirit of the age. It doesn’t, and that is what makes it so interesting, but for me the most exciting new work seems to be motivated by a reluctance to accept any sort of sonic status quo. Georgia Rodgers’ new work for the Bozzini Quartet is plainly titled Three Pieces for String Quartet, perhaps because it approaches the medium as a reservoir of generative resources — tension, resonance, friction — rather than as an ensemble with a 250-year history. Claudia Molitor’s Remember Me… (2012) is an extraordinary work that manages to be intimate and immersive, an opera staged within the confines of a writing desk which belonged to the composer/performer’s grandmother. Matthew Wright’s trance map (2011) project with Evan Parker ignores any conventional distinctions between improvisation and composition, between the histories of saxophones and turntables. It is music which demands, like the new politics, that history be re-made to accommodate the reality of contemporary life rather than to sustain the institutional frameworks of the old world.

–

Christopher Fox’s Qui/nt/et will be performed by the Quiet Music Ensemble on 25 June in the Freemasons’ Hall, Dublin.

Published on 22 June 2015

Christopher Fox is a composer, teacher and writer on music.