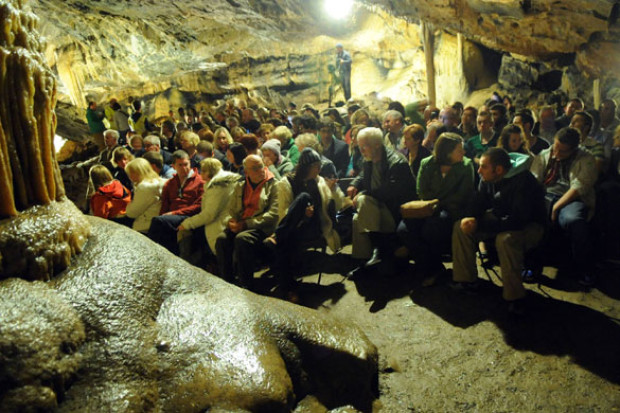

The Dublin Laptop Orchestra performing at the Joinery, Dublin, earlier in the year. Photograph: Daryl Feehely.

Laptops, Activated

Dublin Laptop Orchestra

National Concert Hall, Dublin

25 August 2011

The Dublin Laptop Orchestra was set up as a challenge to electronic music’s primary shortcoming: that laptop performance inevitably leads to a dissociation of music from performer, of a sound from its source. With the six pieces performed at this concert hosted by the Irish Composers’ Collective, the ensemble sought to create electronic instruments, not just electronic works. With each composition, each laptop in the group became a new instrument, with its own unique physical gestures, ranging from the expected typing and mouse-clicking to golf game controllers and the physical movement of the laptops themselves. Individual loudspeakers for each performer — including two specially-made hemispherical arrays, which accurately simulate the motion of sound achieved in acoustic instruments — give a directionality to each instrument, so the music produced by each member of the ensemble comes from that member, rather than from shared speakers. And, unlike the motionless screen-gazing we have come to expect from laptop concerts, the performers crouched, bent, stretched, circled and swooped, making each piece as much a work of performance art as music.

Though some of the works in the concert fell into the usual idioms of much electronic music — an over-reliance on squeaks, blips and rumbles, for example — the novelty of the group’s performance gave each an added dimension. The opener, Atma, was a sweeping spectral work by Donal Mac Erlaine. Dennis Wyer’s Bang-cruncH, conducted by the composer himself, involved the controlling of sound by tilting the laptop itself, while Bryan Dunphy’s 01 used on-board microphones to create an intense piece of real-time improvisatory sampling and looping, the performers clapping, tapping and singing to shape the music. A contrasting piece, Francis Heery’s Spool, was characteristic of its composer, a work of stasis and suspended sound, the performer’s motions gentle and swaying.

Works by the orchestra’s founding members, Alex Dowling and Dan Trueman, stood out. Aonar i Scáth was, in fact, a collaborative piece between Trueman, then a visiting lecturer at Trinity College, and fiddle-player Caoimhín Ó Raghallaigh. By far the most understated work of the evening, Aonar i Scáth had a beauty and depth that belied its outward simplicity, a lone violin voice shadowed by broad sweeping textures of equal parts sweetness and friction. Dowling’s Foxhunters also made use of traditional fiddle playing, but was the only work of the night to focus almost entirely on rhythm. In a direct contrast to Trueman’s work, Foxhunters was complex, driven and energetic. Despite using no external controls — so only the laptop’s keyboard — this was the piece in which the Dublin Laptop Orchestra came together best as an ensemble, with members clearly communicating and feeding from each other’s energy, passing ideas, both scored and improvised, from one performer to another. Here it truly felt that the physicality and energy of acoustic music could translate to electronic performance.

Published on 11 October 2011

Anna Murray is a composer and writer. Her website is www.annamurraymusic.com.