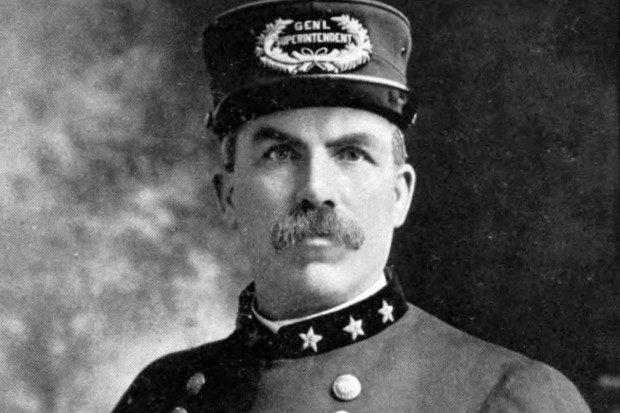

James O'Neill

The Scribe

The main wall of the Chicago flight departure lounge in Dublin Airport comprises a mosaic of usual suspect portraits celebrating Ireland and Irish-America. Nowhere to be seen in this implied ‘who’s who of fame’ quiz is Francis O’Neill whose life story was as if from a Hollywood adventure film.

Having left his native west Cork at the age of sixteen, he travelled the globe working as a sailor, mountain shepherd, teacher and policeman, eventually rising to the post of Chief of the Chicago Police Force. He was a musician and visionary collector of Irish music, best remembered for producing a series of major collections in the first quarter of the 1900s.

If Francis is a glaring absence here, so also is James O’Neill. Born in the small village of Seapatrick, just outside of Banbridge, County Down, he emigrated at 18 years of age to Chicago in 1881. Though no relation to Francis, he too became a policeman. Working privately with Francis the two produced traditional music collections between 1903 and 1908 that have stood together as one of the greatest collections of traditional music in the world, including Music of Ireland in 1903 and the unofficial ‘bible’ of Irish music, Dance Music of Ireland in 1907. Francis O’Neill is well known and his life and work have been documented in Nicholas Carolan’s book A Harvest Saved: Francis O’Neill and Irish Music in Chicago (Ossian, 1997). James, however, has remained an enigma. As a northern fiddle myself, he has always been a great focus of interest for me. Therefore, in finalising James’ biography, I recently travelled to Chicago to confirm some of the details of his life. This article is based on my experiences during that trip.

O’Neill connections

Staying in a hotel on Harrison Street, the O’Neill connections immediately emerge. Francis’ first police posting was on this very street and towering outside my window is the Chicago Auditorium where the O’Neills played all night for Gaelic League activist and eventual Irish president, Dubhghlas de hÍde.

Sunday comprises a session in Chief O’Neill’s Pub. Present are piper, flute-player and owner Brendan McKinney, fiddler Brendan Bulger and accordion and piano player Marty Fahey. Each is the epitome of quality traditional musicianship. Their spirit of fun pervades not only their playing but the banter between the tunes. Towards the end of the session, I meet Jim McGuire by accident. We have been corresponding for some weeks in relation to James O’Neill. Instantly, it is clear that he is a goldmine of information which will radically advance my searches.

The following day on the train to Wynetka to meet Jim McGuire, a young mother sits in the seat in front of me with her baby. She sings her a wee tune. I recall the story of James O’Neill when on duty in the winter of 1901 at 32nd and Halstead Street. He sheltered for warmth in a nearby barbershop. A baby was crying on the floor and its father emerged from the kitchen. Ignoring James, he bounced it on his knee whistling a tune for comfort. James took out his police notebook and began transcribing. Every time the barber got near the ending of the piece he was called into the kitchen. In frustration, James knocked on the door and asked the barber would he please come out and finish the tune. It was christened ‘The Whistling Barber’ and later identified as ‘The Mills Are Grinding’, a title under which it is still played today.

I meet Jim and his research papers confirm James’ marriage, family and death details. Jim had met with Winifred O’Neill, one of James’ daughters in the early 1980s. She confirmed that the family home in Brighton Park had been flooded and boxes of James’ material were destroyed. When he left Belfast, James O’Neill brought his father, John’s, music collections and transcription manuscripts with him. John’s rare material, as well as the over 2,000 of James’ original transcriptions from the collection project were the victims of the routine flooding of the area.

As Winifred described the event to Jim she also astoundingly produced the Holy Grail of Irish music, the sole surviving manuscript of James O’Neill from the O’Neill’s collection project. This copy contains almost ninety pieces of music each of which he had the foresight to date. They range from 1882 to 1904 and many correspond with those appearing in the world-renowned Music of Ireland. This incredible remnant is the one direct link with a vibrant community of musical geniuses who came to settle in Chicago.

Tuesday night and Jim and I attend a session at the house of John Murray, with fellow musicians Tom O’Malley, Pat McPartland and John Meehan. John Meehan is of particular interest to me. He is a fiddle player from my own county of Donegal of whom I had never heard. In chatting we recall the great ‘old lads’ who were the giants of our music. Four thousand miles and decades of time have separated us, yet musically, we are so close that a bee’s wing could not be slipped in the gaps between us.

3522 South Washtenaw Avenue

Wednesday begins with Jim McGuire and I visiting a number of sites associated with the James and Francis O’Neill collection project. The first is 3522 South Washtenaw Avenue. This was James’ residence during most of the collection years.

Francis O’Neill regularly called to this house. He would sit on the porch drinking tea and whistling tunes waiting for James to arrive back from the Brighton Park police station. When the two settled down, the jigs and reels would flow and the furious transcription of the music began in earnest.

Arriving at the address the house is much like I had come to expect, a modest family home for a man of similar traits. The significance of it for me, however, is that this cottage was the venue of what is considered by many authorities as the collection site of the greatest documentation of ethnic music. Here the musical heroes of Ireland – O’Neill, Delaney, Early, Cronin, McFadden, Kennedy, Touhey and more – played their hearts out and that music was captured. Francis O’Neill persistently referred to this house as ‘Mecca’. Few players of Irish music have ever visited this site, including most of those in the Chicago community, yet to us it truly is Mecca.

The next stop is with Sligo piper and flute player Kevin Henry who came to Chicago in 1951. Within five minutes I feel as comfortable as in any house in the Irish countryside. There are four thousand miles and at least two decades of age difference between us but in no time we’re speculating on the musicianship of players who died a generation before we were both born and most importantly we are laughing at shared jokes and stories. This is the brilliance of the music. It is not just the two-dimensional performance of melody lines. It is the full three dimensions of all the hilarious nonsense and humanity in between. Kevin Henry is that knowledgeable and fun that he is stretching into a fourth dimension. We part laughing. If we never meet again it is not important; we did meet and were enriched by it.

The next morning has me in the Harold Washington Library scanning every edition of the Daily News for 1911. James was photographed in relation to a court case about which I had no information. The hunt initially proves in vain. I discover, however, that autumn 1911 was marked by three police scandals. Clouds are left hanging over James’ impeccable character.

Switching to the Chicago Tribune for the last quarter of 1911 confirms that on Labor Day 1911, a wrestling match took place in Comisky Park. Reports of public betting were notified to Captain McWeeny who relayed instructions to notify all on-duty policemen to investigate and make arrests. Despite the recording of numerous gambling incidents from the public no arrests were made. The public outcry forced an investigation in which all officers on duty were implicated, including James O’Neill. The result confirmed that a Lieutenant never relayed McWeeny’s instructions. James and all other officers were fully and publicly exonerated. The clouds over his good character have risen.

Celebration and loss

The afternoon is a journey of revelation. I take the Orange Line to Bridgeport and locate the site of the old Deering Street (now Loomis Street) Police Station, now a small playground. I find James’ second home on Wood Street and then travel over to Western Avenue and the site of James’ third residence. I walk back to Eleanor and Fuller Streets near the old Bridgeport Pumping Station. James shovelled coal here on a twelve hour shift seven days per week. The sense of struggle and striving to settle in a new world is still tangible walking these streets.

At the Thirty Second and Halstead intersection I look around for what might have been the site of the famous ‘Whistling Barber’ event. There is one, clearly very old building standing alone. It was certainly open for public business when in a healthier state but the lace curtains seemingly conceal everything. Peering in I see two large round circles and empty bolt holes on the floor. Remnants of where a barber’s chairs had been fixed. I feel a rush of mixed emotions and connections. Somewhere in Ireland a man left in search of a greater life in America. It brought him to this very spot. By quirk of fate and James O’Neill’s astounding musical diligence, his simple act of whistling a reel from his community’s repertoire thousands of miles away resulted in a small but important piece of Irish cultural history which lives on.

Two days later I travel with Francis O’Neill’s great-granddaughter, Mary Lesch, and historian Ellen Skerritt. We finish our tour at Mary’s house. She shows me a family heirloom. It is Francis O’Neill’s tin whistle, an early Clarke make in the key of D. I’m encouraged to play and choose ‘East at Glendart’ a tune Francis had learned in his childhood. He brought it with him to Chicago and it appears in the 1903 collection under that name. He must have played the same tune on this whistle. Again, joy of celebration and sadness of loss arrive as welcome twins in an instant.

James died following a heart attack in Saint Anthony de Padua Hospital on November 28th 1949 at the age of 87 years, and is buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery. Owing him a massive debt of gratitude for more than forty years as a player, a tune at his graveside is a minimal, but fitting, act of repayment.

Published on 1 July 2005