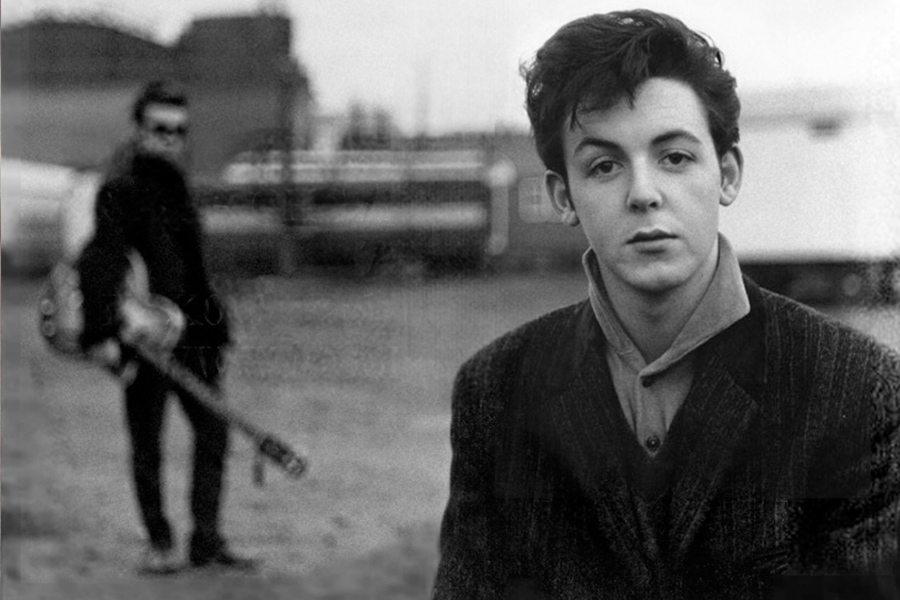

Astrid Kirchherr’s portrait of Paul McCartney in Hamburg in 1960 with Stuart Sutcliffe in the background.

Why was Hamburg the Perfect Fit for the Beatles?

Hamburg belongs to the ranks of legendary rock ‘n’ roll cities, mainly because of the 250-plus nights The Beatles played there between 1960 and 1962. The port city was a key site of their early, primitive phase where they once lived in the squalid Bambi Kino and a drunken John Lennon played a gig wearing a toilet seat. It also saw them evolve into a tight outfit capable of winning crowds with marathon sets of four-four stompers. Other bands associated with what became known as the British Invasion also honed their chops on the same stages, leading one writer to dub Hamburg the ‘cradle of British rock’. The gloriously uninhibited spirit of Hamburg rock ‘n’ roll threaded its way into punk in the 1970s and garage band revivals since the 1980s, its flag flown by performers from Billy Childish to the White Stripes.

When I first arrived there as an exchange student in 1986, one of my earliest experiences was a ‘funeral march’ for one of Hamburg’s hallowed stages, the Star Club (it was being razed after a devastating fire). As I surveyed the crowd of mourners, I began to wonder what it was about Hamburg that gave it its particular affinity for rock ‘n’ roll. What did this music mean in this particular place? Why did these Germans invest such emotional energy in it while my own country, the United States (which spawned the genre, after all), took it for granted? I also began thinking about what it might have been like to be at the Star Club or one of Hamburg’s other legendary venues. How did it feel to be at a show in the early sixties when parents and preachers still considered rock ‘n’ roll disreputable, even degenerate and racially taboo?

Wirtschaftswunder

Understanding early rock ‘n’ roll in Hamburg means exploring the neighbourhood where the clubs were clustered: St Pauli, a portside entertainment zone that was also home to one of the world’s most notorious red-light districts. Rock ‘n’ roll gained a foothold there around 1960 due to a confluence of factors.

West Germany’s fabled Wirtschaftswunder (‘economic miracle’) brought waves of tourists to St Pauli seeking distraction from the stresses of the present and the ghosts of the past. The economic miracle also put unprecedented levels of disposable income in the pockets of teenagers and young adults. Growing purchasing power and sheer numbers enhanced these Baby Boomers’ identity as a distinct cohort that was more mobile, less bound to traditional social categories, and open to new sensations, particularly from the United States.

In late 1959, a St Pauli entrepreneur named Bruno Koschmider sought to tap this new market by opening the Kaiserkeller, a ‘dance palace for youth’. But initially this basement club attracted little notice, so Koschmider continued to search for a gimmick that would distinguish it in a crowded entertainment landscape. He found it in rock ‘n’ roll, which by this time had been driven underground in West Germany after violence at showings of Rock Around the Clock and Bill Haley’s 1958 concerts.

Beat music

Koschmider’s experience booking Dutch-Indonesian ‘show bands’ who played rock instrumentals suggested there was an audience for this music. In 1960, he began importing British acts such as Tony Sheridan and the Silver Beetles. These young Brits came cheap, could sing the music in its native tongue, and brought a gutbucket quality that St Pauli audiences appreciated. Soon other entrepreneurs copied Koschmider’s success, spawning a wave of new clubs such as the Top Ten in late 1960 and the Star Club in 1962. By the Beatlemania year 1964, St Pauli had an infrastructure of clubs, pubs, snack bars and other businesses catering to the thousands who thronged there for what was now called beat music.

Rock ‘n’ roll succeeded in early 1960s St Pauli in part because it was new. Beat clubs offered young people places to experience live a music that had few German outlets then. While the Kaiserkeller’s initial audience was an assortment of sailors and workers in the local sex industry who just wanted party music, they were soon joined by working-class Elvis enthusiasts and bourgeois bohemians. Those more dedicated fans could now connect with each other, even if class barriers stubbornly persisted. Many also formed bonds with musicians in the intimate spaces of the clubs. These interactions created a music scene with a distinct sound and style.

Liberation

What participants did in club spaces and the ways they used beat music gave it broader significance, presaging the dramatic social and sexual challenges of the late sixties. For example, Star Club owner Manfred Weissleder, who started as a local strip-club mogul, became a vocal advocate of young people’s right to public space and their own leisure. He founded West Germany’s first serious rock magazine in 1964, using it both to promote his music empire and to question prevailing notions of respectability and authority. Fans’ uses of music also worked against the oppressive conformism of the Adenauer era (1949–63), which prioritised hard work and ‘family values’.

That atmosphere found musical expression in the chart dominance of Schlager, German-language songs without syncopated rhythms that conveyed sentimental or nostalgic themes. For young people alienated by all this, rock ‘n’ roll offered an antidote to German provincialism. It was loose, offering bodily liberation and cultural engagement with African-American culture in particular.

Within the Hamburg scene British musicians and German fans, male and female, found avenues to explore sexuality and connect across national lines. Participants like Astrid Kirchherr found in rock and beat inspiration for aesthetic experiments in fashion and photography. The styles she and other fans created were picked up by musicians (most famously the Beatles, whose mop-top hairdos came directly from their Hamburg friends), who in turn circulated them back in England and later the world.

Frenetic tension

While St Pauli was not the only place in Germany to experience rock and beat between 1958 and 1964, it brought unique elements that helped the music evolve into the transnational language of youth in the sixties. A night out in St Pauli always crackled with the possibility of violence as music fans rubbed elbows with sailors, gangsters, prostitutes, transvestites and barflies. Police and welfare officials, anxious about the presence of youths in this milieu, often raided music clubs after curfew and incarcerated teenage runaways. This sense of danger shaped the music, a frenetic tension you can hear in early records by The Rattles or the Beatles’ Star Club bootlegs. As a cosmopolitan port district, St Pauli was also marked by the flow of people and goods from around the world. Rock ‘n’ roll was a perfect fit for this place. British musicians and German fans used American cultural forms to experience the pleasure of difference and express their nonconformity. For young Germans, these held out the possibility of cultural rejuvenation and transcendence of their country’s racism.

At the same time, such acts of distancing were usually limited to the spaces of the music scene. The only politics openly pursued there were those of fun. Most fans combined participation in the music scene with the obligations of work or school. Even as young women pushed at the boundaries of gender by seizing on new avenues of physical mobility and bodily pleasure (from dancing to sex), most eventually accepted the roles society had in store for them. Sexism and homophobia did not disappear, even if racism was considered uncool.

Hip clothes

So, was the Hamburg scene merely weekend rebellion dressed in hip clothes? Not entirely. Participants in the scene generated their own knowledge and lived out new values in their private lives. They didn’t use music to solve social problems, but the things they did with it loosened the grip of postwar sexual and emotional repression. Engagement with other cultures through music opened up alternative ways of seeing, moving and thinking. The music scene in one of Germany’s most cosmopolitan zones also prized tolerance as a good – no small thing in a country only just beginning to confront its terrible past and its lingering prejudices. Rock and beat didn’t instantly transform German society, but they were important to its ongoing processes of democratisation and liberalisation.

Finally, exploring rock ‘n’ roll in the particular place of St Pauli lets us see the music not only as something new, but as part of a longer continuity in the masses’ uses of entertainment. The spaces of the Hamburg music scene had been sites of ‘amusement’ of one kind or another since the nineteenth century. The Kaiserkeller stood on the same site as a bar where Nazi-era Swing Youths jived to forbidden Ellington and Basie records. The Top Ten had once been a hippodrome where sailors on shore leave got drunk and rode draft animals. The Star Club opened in one of St Pauli’s many movie theaters – cinemas that faced bankruptcy in the early 1960s as television sucked away their customers.

It took moxie to go to the beat clubs before the mid-1960s, particularly if you were underage or female. Your desire to be in those spaces had to push past the objections of your parents, potential harassment by the law, and the sleazier aspects of street life in St Pauli. But as we know from police reports, press accounts, artefacts and interviews, thousands of young people were willing to take the chance. Nowadays, as rock music has become so mainstream that young people consider it the tired sound of their parents (or even grandparents), it’s useful to be reminded of a time and place when it signified rebellion against a hostile world. For German fans raised in an era of stifling conformity and psychic repression, it felt like salvation.

Published on 22 August 2018

Julia Sneeringer is Associate Professor of History at Queens College and the Graduate Center, City University of New York. She is the author of 'A Social History of Early Rock 'n' Roll in Germany: Hamburg from Burlesque to Beatles' (Bloomsbury Academic, 2018) and 'Winning Women's Votes: Propaganda and Politics in Weimar Germany' (2002).