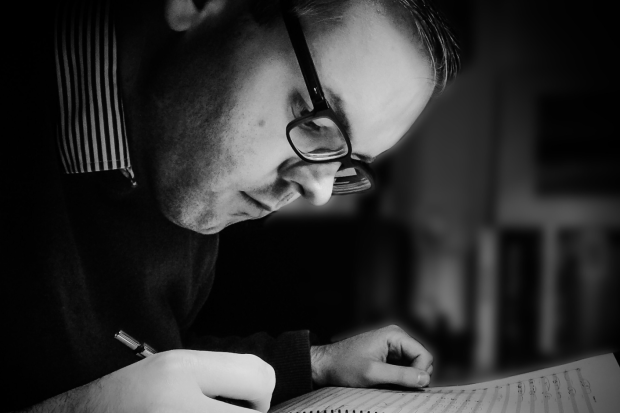

Nathan Pilatzke, Jonathan Kelliher and Matthew Olwell in Siamsa Tire's 'Anam' (Photo: Siamsa Tíre)

A Summer Without Siamsa – Are We Forgetting About Local Arts Communities?

With disappointment, I heard of the decision to cancel part of this year’s summer season of performances by Siamsa Tíre, the National Folk Theatre of Ireland. For many years, I performed in the productions for the summer but am now living away and am no longer involved with the company. The news, however, raised questions in my mind regarding how we value and support local arts communities, particularly, but not exclusively, in Irish traditional music, song and dance.

The 2023 season, marketed as a ‘Festival of Folk’, was to include the productions Anam and An Ghaoth Aniar in addition to a revised version of one of the original Siamsa productions, Fadó Fadó. These have now been cancelled. The shows demonstrate different aspects of the theatre’s mission: Anam brings together step dancers from four related traditions reflecting a shared culture, while An Ghaoth Aniar features a larger local community cast and utilises modern sets and staging to present Irish traditional music, song and dance from the west of Ireland.

Siamsa Tíre emerged from community activities in the 1960s and developed a theatrical representation of Irish culture that incorporates traditional music, song and dance with reference to ways of life and folklore. Although the summer season is but one aspect of Siamsa Tíre’s programme, its associations with tourism sometimes negates an appreciation for the role it plays in developing artistic expression, often through collaboration.

‘Non-profit making productions’

The 5 June statement by the board and management of Siamsa Tíre – and there has been no more information forthcoming since – referred to the suspension of ‘all non-profit-making productions after 17th June 2023, and for the remainder of the summer season’. The reference to ‘non-profit-making’ suggests that the matter at hand is purely an economic one; it ignores deeper cultural questions around what Siamsa Tíre is.

The statement continues: ‘the venue remains open for business and will continue to be a community cultural hub, hosting a wide variety of performances across theatre, music, dance and the traditional arts for local audiences and visitors to the southwest.’ But Siamsa Tíre is not just a building; it is a community with a philosophy. Opened in 1991, the Siamsa Tíre Theatre and Arts Centre is a wonderful facility for the town of Tralee but it is the community cast that gives it its soul. It is a part of the vision for engaging with folk culture – traditional music, song, dance, local customs and narratives – first outlined in a document written by Fr Pat Ahern in 1972.

The building is only one part of a more extensive plan that sought to present Irish culture on stage: two ‘Tithe Siamsa’ buildings located in the villages of Finuge and Carraig were opened in 1974 and 1975 respectively. These (formerly thatched) cottages were training centres that I myself attended. I had classes in music, song, dance and mime in a space dominated by a turf fire and open hearth surrounded by flagstones donated by founding members, including the leac from the Ahern homeplace. I was enthralled by stories of my teachers performing on Broadway in 1976, excited by the experiments in dance (including the choreography by Anne Courtney to Mícheál Ó Súilleabháin’s Idir Eatarthu/Between Worlds) that brought in dancers from other cultures, challenged by the demands of reaching a standard to perform for the summer season, which was the ultimate goal of many of my friends and me. I grew into Siamsa Tíre at a time when the theatre was very often full from Easter to autumn, mainly with tourists enjoying shows created primarily by the local community with a little help from outside choreographers, composers and designers.

Siamsa Tíre has been recognised as both traditional and innovative in its artistic presentations. Nevertheless, the June statement suggests a need for a change of direction by the company: ‘This decision enables the National Folk Theatre offering to be reimagined in an exciting and innovative way that, while honouring our tradition and heritage will be more relevant to contemporary audiences.’

This devalues the innovative nature of what Siamsa Tíre had already achieved and in essence reiterates what Ahern and the founding members set out to accomplish. They demonstrated how we can embrace the sounds and rhythms of the past, in parallel with new approaches, compositions and sounds, and that these choices are not mutually exclusive.

The Siamsa arts ecosystem

Siamsa Tíre created a space in which artists could, in their own community, strive towards artistic excellence in the exploration of the traditional arts, informed by an understanding of how ways of life inspired the creativity of previous generations in Ireland, and involving professional artists not only from this country but around the world. Some members aspired to careers in the arts but others continued to perform while embarking on other professions.

I admire many artists that I shared the Siamsa Tíre stage with, including Paula Murrihy, Sarah Jane Drummey, Muireann Nic Amhlaoibh, Conor Moriarty and David Geaney. They have forged successful careers in the traditional arts, opera, film, dance, music and musical theatre. From the West End to Hollywood, the seeds planted in Finuge and Carraig blossom all over the world. Many, like myself, were also involved in Comhaltas and musical societies and learned from local music, song and dance teachers in what is a vibrant arts ecosystem in Kerry. In Tralee and elsewhere, these creative individuals contribute to the artistic scene where they have made their home as part of groups, choirs, ensembles and more. Dr Susan Motherway and Dr Sharon Phelan of Munster Technological University, and myself at Dundalk Institute of Technology, have all pursued doctoral studies informed by our experiences and bring this into our lecturing and research. Still others remain committed to Siamsa Tíre and, until this month’s decision, performed as part of the summer season with – not just in – the theatre. We were not guided on these pathways by the bricks and mortar of a receiving theatre but rather the human beings who are the embodiment of folk culture.

Creative communities

This is not just about Siamsa Tíre. I was reminded of Michael McGlynn’s statements regarding his dissatisfaction with the Arts Council’s support for Anúna. Despite developing a globally recognisable and acclaimed approach to choral music, and creating a pathway for many young Irish singers including Hozier, the limited financial support has led to the group moving their activities overseas. More locally in Kerry, a conflict has arisen around Listowel Writers’ Week whereby the longstanding voluntary committee has been replaced by a professional curator following a consultant’s report funded by the Arts Council. This has undermined the community roots of the festival and resulted in local anger. In his recent doctoral research at Dundalk Institute of Technology on traditional music in North Dublin, Maurice Mullen critiqued the policies at local and national level that appear to have a blind spot for community activities and the evangelists and cultural leaders who energise and engage people at a local level. Perhaps we have become obsessed with earning a living from the arts to the detriment of many who just wish to be part of a creative community.

I have no doubt that Siamsa Tíre requires ‘a new way forward’, as the board’s statement describes it. Changes in tourism, local arts opportunities, tastes and policies are all factors in a complex story that, in the case of the theatre’s 2023 summer season, is being simplified, failing to recognise the long-term significance of all that is Siamsa Tíre. It is important to recognise the broader activities and benefits of community-based arts groups and, instead of under-valuing them, develop funding models that contribute to their sustainability.

For more on Siamsa Tíre, visit https://siamsatire.com.

Subscribe to our newsletter.

Published on 20 June 2023

Dr Daithí Kearney is Co-Director of the Creative Arts Research Centre at Dundalk Institute of Technology.