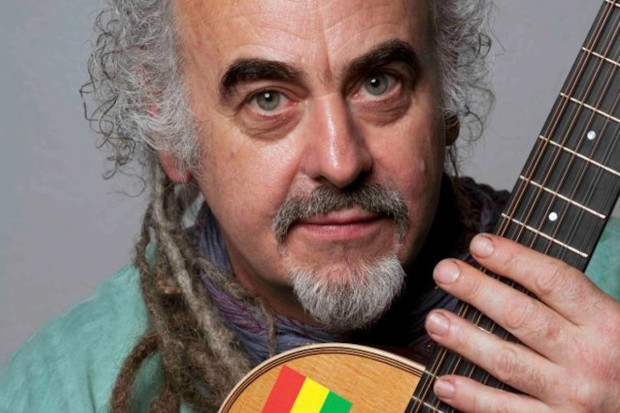

Gary Keegan and Danny O’Mahony in 'Bellow' (Photo: Ste Murray)

Making Bedfellows of Traditional Music and Experimental Theatre

Ostensibly, Bellow is a play about North Kerry traditional musician Danny O’Mahony, providing a platform for the accordionist to tell the story of his relationship with both the instrument and the tradition in which he operates. As such, we get a potted history of significant moments in his 40-years-long-and-counting life in music and we are left in no doubt how much it matters. Not just the music, but the very tradition itself. There is no doubting his mission to preach his gospel to territories beyond his traditional – in every sense – audience.

To that end he took the unorthodox step of approaching the theatre company Brokentalkers with a view to achieving this aim. Quite how he decided how Brokentalkers, an avowedly experimental and boundary melting experimental company, would achieve his objective is perplexing. It is not quite, after all, National Theatre levels of projection and amplification. Nevertheless, his faith has proved rewarding.

This being a Brokentalkers show (I say show, but more on that anon) it is highly self-referential. While Brokentalkers co-founder Gary Keegan acknowledges and delights in the incongruity of making bedfellows of traditional music and experimental theatre, it’s certainly a fascinating meeting of minds and worlds. Brokentalkers have covered such big topics as institutional abuse, the refugee crisis and extremism in quite unconventional ways, but O’Mahony was convinced he could trust them with his story when he saw Woman Undone, their daring collaboration with singer Mary Coughlan.

First meeting

When O’Mahony was traditional artist in residence at UCC in 2019, he approached the Department of Theatre for ideas on how to present what he does onstage in a different context and they suggested Brokentalkers. In the opening section of Bellow, with Keegan and O’Mahony on stage, the former recounts their first meeting in the Clarence Hotel. This episode sees both parties chafe against each other in a rather amusing manner, like a real droll odd couple. When Keegan declares that what the company does are pieces, not shows, O’Mahony wonders if that just makes them sound incomplete.

O’Mahony proposed a scenario that involved him sitting down and telling his story. While Keegan appreciated the charm and authenticity of this approach, he feared it was too traditional. ‘What’s wrong with a guy sitting on a chair and telling a story?’ queried the musician. Countering that theatre allows for all sorts of possibilities, Keegan suggests, rather comically, that Danny could stand on the chair. ‘It’d still be telling a story,’ the Kerry man deadpans.

Danny O’Mahony in Bellow (Photo: Ste Murray)

Danny O’Mahony in Bellow (Photo: Ste Murray)

It’s obvious which one is the actor and which one isn’t. Clearly not polished in the art, O’Mahony’s onstage awkwardness adds to the aforementioned charm and authenticity. He may be in unfamiliar territory, but he’s game. And he’s not without his creature comforts. In traditional music, the tools of the masters are venerated, and the late Tony MacMahon gave his famous accordion to O’Mahony before he died. Bellow’s simple set of some red drapes and a table features a low wall adorned with the accordions cherished by the Kerry musician.

Young Danny

Danny recalls staring for hours at the glare of the mother of pearl buttons on his first accordion. He was 10. The narrative, through the device of a postcard home, puts the 12-year-old musician in New York. It feels scarcely credible that a child could actually find themselves in this situation, and without a chaperone, apparently. The contents of the card detail a very adult world and it feels like it was penned by someone more worldly than an Irish country boy. But it is illustrative of how the young musician was treated as he made his way in his career. Without explicitly commenting on it, this section suggests that life on the road took a toll. But O’Mahony’s zeal for playing saw him travel far and wide. As a 16-year-old, he thumbs to Kilkenny to compete in a Junior All-Ireland accordion competition. A life dominated by travel, concerts and achievement is brought to life.

At this point, Bellow introduces a third cast member, dancer Emily Kilkenny Roddy, who plays Young Danny. In typical Brokentalkers style, she wears a mask of a red-headed boy and is dressed in the typically early 1980s clothing that is captured in a photo of the young man. In one scene, Young Danny’s top is covered with medals, while on audio a dizzying treadmill is evoked by an exhausting and exhaustive list of towns and cities from Gneeveguilla to Helsinki to Chicago and all points in-between. The scene culminates in a road accident. It’s not quite clear how Danny arrived at this nightmarish portrayal of illness and alcohol. Bellow doesn’t dwell or delve too deeply on this episode of O’Mahony’s life. I might surmise that such an investigation would alter the focus of the play. Suffice to say that it is quite a visceral and nightmarishly realised scene, and the image of Young Danny spasming and trying to cling to his instrument leaves a searing impression.

Emily Kilkenny Roddy and Danny O’Mahony (Photo: Ste Murray)

Bellow is not without its layers of psychological shading, albeit delivered without bald explanation. A central aspect of the play is the device of what I call the Cowboy Huckster, a cute hoor Kerry man played broadly by Keegan in full Wild West attire. He appears early on in the show, and it’s unclear if he represents an individual or a collection of people who heaped pressures on the young prodigy and, perhaps, even exploited him in some way. In a darkly amusing turn Danny symbolically dispatches him with a six-shooter as Keegan begins quoting Chekov’s dictum about a gun.

‘Did that work?’ Young Danny asks.

‘No,’ says O’Mahony. ‘I can still hear his voice.’

Communicating the tradition

For a project that was conceived not only as a way of telling O’Mahony’s story, but also to communicate the tradition to a different audience, there is a measure of underlying sadness and, dare I say, trauma.

The title Bellow may refer to the lungs of the accordion, but it could also be an expression of rage against the dying of the light. A sandwich board-type sign placed on the stage declares that ‘Tradition is the Future’. Tradition requires artists and practitioners to ensure its existence. Unfortunately, their ability to do so is limited. Time catches up with us all, and the cast’s thoughts turn to when they can no longer do what they love anymore. Kilkenny Roddy considers the limitations of age on a dancer’s body. Reckoning that it takes 18 months to make a show like this, Keegan calculates he has ten pieces left. For O’Mahony, the very idea of being without his instrument would be like losing a loved one, disabling. In one passage, scored to a soundscape of melancholy drones, ghostly accordion and rumbling atmospherics designed by Icelandic composer Valgeir Sigurðsson, an accordion-less and uncertain O’Mahony explores the movement his arms and fingers make while playing. It’s a sad, almost tortured image. The impression the instrument has made on the musician is astutely noted by Keegan who perceives Danny to be imbalanced, observing that the left hand side of his body is bigger and heavier than his right. There are also more sensory impressions and Proustian associations. Each time he plays MacMahon’s accordion, O’Mahony says he can smell his cigarettes.

Bellow ends on a profound and beautifully theatrical note. After delivering a monologue on tradition, O’Mahony plays one last tune. As he does so, Keegan and Kilkenny Roddy place life-size, mostly black-and-white photograph cut-outs of six box players (one of whom is female) and a fiddler, behind him. Who are these characters? Figures from O’Mahony’s North Kerry community and family, or are they more nationally known? The audience clap gaily along, but it is a tableau that is overwhelmingly conflicting. It is great that a hat is being tipped to these figures, these anonymous and perhaps unsung heroes. But alongside the affirming joy that a community, a history and a lineage is palpably present and being celebrated, there is something poignant in seeing this lone figure surrounded by ghosts. Of course, they are not ghosts as far as O’Mahony is concerned, but it reminds us that one day he will join them. In the most serene manner, he rages, a custodian of tradition fighting against time to deliver it to the future.

As Keegan ventured much earlier in the piece: ‘Are we really doubting something that obvious? A show about the healing power of music.’

And art, Gary. And art.

This performance of Bellow took place at the Everyman in Cork on 13 March 2024. For more, visit https://brokentalkers.ie.

Subscribe to our newsletter.

Published on 22 May 2024

Don O'Mahony is a freelance arts journalist based in Cork.