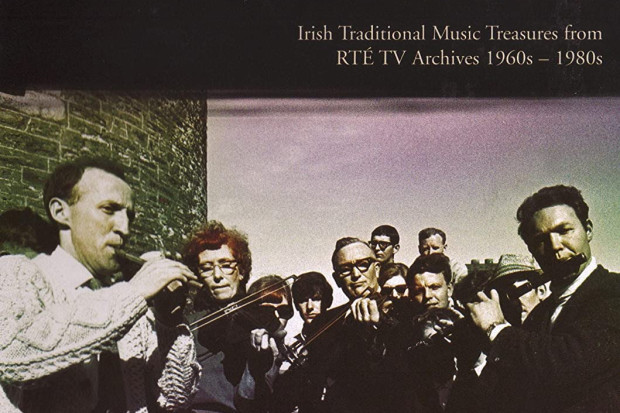

Tony MacMahon in ‘Slán leis an gCeol/Farewell to Music’

Look Forensically into My Mind

The first feeling is one of shock. Out of nothingness comes the voice and then, in close-up, the face of Tony MacMahon, one of the great players of traditional music in modern times. He is staring into the camera, staring at us, challenging us to take in the wrecking effect of an advanced tremor. Has it come to this? Is this the player whose first eponymous LP in 1972 demanded to be heard as an artistic statement, whose work for radio and television brought freshness and enthusiasm to the diffusion of traditional music, who offered many players their first public exposure, and whose duo recording with Noel Hill, I gCnoc na Graí – spontaneous in feel but brilliantly set up and produced – put the listener at the heart of a joyous communal occasion? Is this the man who, never using his high public profile to churn out recording product, gifted us such further landmark recordings as Aislingí Ceoil, MacMahon from Clare and, sadly, Farewell to Music. And are these the shaking hands of the man for whom sureness of touch and instinct-in-the-moment were everything?

It would be easier to turn away and take refuge in one of those recordings than to accept the challenge MacMahon throws down from the outset:

Why am I talking to this piece of glass and metal? Why? Why? My fear is that I will die without my family being able to look forensically into my mind. And that is the only reason I’m talking to you here today: so that some little record may be available of my tormented soul. Some little record… Some little record…

He announces that he is going to ‘unearth the roots and entrails of [his] twisted past.’ Don’t come this way for a melancholic and fond farewell to music. He is going to lay out ‘every little knot and crevice of thought-cancer.’ If that is not clear enough, try this: ‘Stand back. Have a good gawk – and then I’ll piss on them, curse them, fuck them… So here goes.’

The ecstasy of music-making

The frustrations of a creative spirit locked into a deteriorating bodily apparatus are made vivid to us in the documentary film Slán leis an gCeol/Farewell to Music. To have words on the tip of one’s tongue but to be forced to pick one’s way painfully towards a complete sentence – ‘It is my mouth drying up. It is the world around me drying up. It is despair’; to have music in one’s mind but no longer in one’s fingers; to search for memories and find that chunks of the past have fallen away; the effects of advancing age are accelerated and accentuated by MacMahon’s tremor, which has been diagnosed, inconclusively, as Parkinson’s or dystonia. It is heart-wrenching to see the MacMahon of today, seated in a shadowy room, watching his younger self caught in the ecstasy of music-making with Barney McKenna as captured in The Green Linnet, the 1978 TV series that followed the pair as they brought their music to locations across Europe.

The opening paragraphs of this review have been about Tony MacMahon, the man, the musician, the story. We are not, however, at home with him. We are watching a collaboration between the musician and an invisible film-maker. It is a tribute to producer and director Cathal Ó Cuaig’s skill that the artfulness with which he has shaped the film draws attention to MacMahon rather than to itself. I have no knowledge of the film-maker’s artistic influences, but let’s go back to the idea of a man in a room going over recordings of his earlier life. Krapp’s Last Tape, one of the plays of Samuel Beckett, features an old man in his ‘den’, late in the evening, digging through a trove of old tapes, and lingering over and commenting (with a mixture of dark irony and wonderment) on the moments selected as especially meaningful by his younger self. In typical Beckett fashion, lyrical moments are liable to be cut off before we can be caught up in them.

The cutting off of any immersion in the joys of MacMahon’s music is one important way in which this film strongly marks itself off from the tribute form. The film-within-a-film technique is another, especially as it sets sun-filled shots within a shadow-laden house interior. The focus on the anguished condition of the musician is maintained as much through such formal, visual means as through the words that are spoken. If Slán leis an gCeol shares footage with the homage to MacMahon in the ‘Sé Mo Laoch TV series of some years ago, it is here put to entirely different ends. The usual sequence of friends and admirers recounting their meetings with, and admiration for, the great man is entirely excluded. In fact, the film enacts a remarkable meeting of minds.

Creative mind, destructive soul

In his director’s notes, Ó Cuaig is very clear on his aims: ‘Although I greatly respect and admire the work Tony has done in his life, I didn’t want the film to be a hagiography. Instead I wanted it to be an unapologetic exploration of the tortured mind of an artist from the inside.’ He also says that his aim was to highlight ‘the paradoxical relationship between the creative mind and the destructive soul.’ The words could be MacMahon’s own as he contrasts ‘the pure oxygen of artistic achievement’ with a dark seam of feeling going back to his childhood. The silence surrounding his father’s sudden death (‘Thit sé mar chrann gan torann’ [He fell like a tree without a sound]) is one deep wound. Making music, the stepping into a space beyond the self – this offered MacMahon an escape from the dark of depression. Now, with no hope of recovery from his illness – shots of MacMahon listening to his own disembodied voice speaking optimistically on radio of a return to music-making only deepen the darkness – he is contemplating assisted suicide, as the nation learned during an appearance on Joe Duffy’s Liveline radio programme. What point would there be in suffering through the further physical and psychological humiliations and frustrations of the last stages of life in this condition?

Here we are on inherently difficult territory. It is only on stepping back from the experience of watching that further questions and issues arose for this particular viewer and reviewer. ‘I was not present,’ he says at one point. Elsewhere, ‘I killed the love of my wife and children.’ If he has agreed to make this film solely in order to leave a record of his soul for them, is a public film the best way to do this? Knowing neither MacMahon nor his family, I can imagine parts of the film (the way a family story about Christmas is used, for example) being open to a counter-reading: as a self-pitying plea for understanding and forgiveness, and one not without a hint of accusation. It is the public man who gets to present his side of the story, even if it is one of sometimes raw self-exposure.

Judgements on music

At some level, MacMahon’s statements of inadequacy are of a piece with the shape of his whole life. He was never just a player. While paying heartfelt homage to the greats of the tradition, he was probably always seeking more from the music than any of his predecessors did – and indeed may well have found more. The depths of what he drew from slow airs like ‘The Wounded Hussar’ account for the impact of his first recording. (Years later, after a gap in listening, I was surprised to find myself at least as taken with the supple lilt of his jigs, reels and hornpipes.) The totality of statement, the artistry, that MacMahon sought had as its obverse a dismissal of music that contented itself with routine or with being a pathway to commercial success. He was typically fearless and uncompromising in naming names. His life has been structured on a divide between highs and lows; his judgement of music on a divide between the authentic and the banal. And his own ecstatic playing, it seems, was set against the misery or lifelessness of the everyday.

For him, there is no in-between-ness; there is no value in everyday existence. Perhaps MacMahon’s auto-critique partakes of this same intensity of self-absorption. Does it leave enough space, not for us the general viewers, but for the experience of those it intimately addresses? Perhaps a flat cataloguing of the day-to-day form in which he failed and hurt those he loved would speak more meaningfully across the divide of time and alienation? But whether speaking or playing or writing, MacMahon operates almost exclusively in the key of fervour.

Slán leis an gCeol/Farewell to Music stands (and withstands questioning) as an absorbing and subtly constructed exploration of matters of life and death. It is respectful of the man whose courageous self-exposure is at its centre and it is admirable for the way it challenges viewers while offering them the space and distance to define their own responses.

Slán leis an gCeol/Farewell to Music is available to view on the RTÉ Player.

Published on 13 March 2019

Barra Ó Séaghdha is a writer on cultural politics, literature and music.