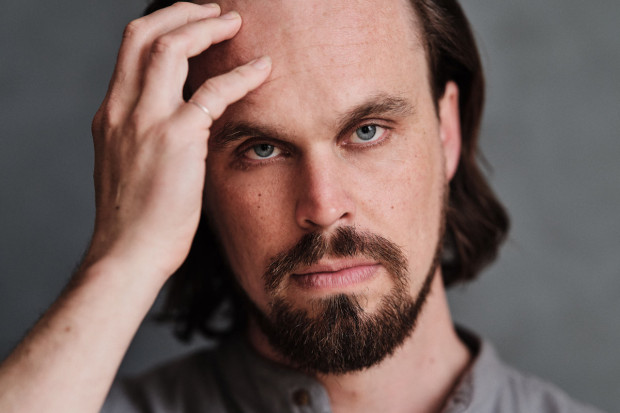

Peter Broderick (Image: Sebastien Toulorge)

When Everything Breathes: An Interview with Peter Broderick

In June 2017, shortly after Peter Broderick moved to Ireland, he received an email from the Athenry Music School. A parent had suggested adding some of the American composer’s music to the repertoire of the school orchestra, and the Director, Katharine Mac Maghnuis, sent him an email enquiring about sheet music. She presumed he lived in the United States. In a little over an hour, the reply came: he was less than an hour away.

Mac Maghnuis and Broderick met, and while he didn’t have any of his music written down, they developed an idea for a new commission, a piece called When Everything Breathes for youth orchestra and choir. The premiere, last April, was a powerful experience for the students and parents; Mac Maghnuis was moved to tears.

Broderick is married to the Irish singer Brigid Mae Power and in 2016 they moved to Galway. The majority of his work is abroad, however, and so his engagement with musical life in Ireland to date has been relatively light. Last year he performed at the Galway Jazz Festival and at the Pavilion in Dún Laoghaire. He also applied for a residency at the Sirius Arts Centre in Cork in 2016, which led to various performances and a new commission, and he featured in Myles O’Reilly and Donal Dineen’s This Ain’t No Disco series with his musical collaborator David Allred, also a singer and multi-instrumentalist. Broderick is currently working on music for an 11-hour film and installation by Idaho film-makers Vernon Lott and Jennifer Anderson.

‘Britches Full of Stitches’ in Oregon

Broderick grew up in Oregon on the north-west coast of the States. Both of his parents are folk musicians. When he was a child, they would bring him to gatherings in a neighbour’s house. While his parents and their friends would play music and sing downstairs, he would be upstairs playing computer games with the neighbour’s children.

But growing up in a house full of instruments meant music seemed inevitable. He began classical violin at the age of seven, but was also taught some Irish and American folk tunes – he can recall the Irish polka ’The Britches Full of Stitches’.

His entrance into professional performance began in his early 20s when he joined the Danish alternative band Efterklang, who he met over the internet.

I met them through MySpace, one of the earlier social networks… I met them just as a big fan. At that point I had played in a lot of bands. I had made music on my own, but I didn’t really do much with it at home, so I started putting it on MySpace. Somehow I got the guys from Efterklang to listen to it. We kept in touch for a while and they ended up inviting me to Denmark to join their band and also support them as a solo act – I had never even played a solo show before.

Broderick’s music at that stage was mainly instrumental, influenced in particular by Max Richter.

I wanted to sing but I didn’t feel that I had much to say at that point… When I got the invitation to tour with Efterklang and play support for them, I realised very quickly that I wanted to sing.

There’s something about singing that’s just so immediate. To play the piano on stage is one thing, but to turn to the crowd and sing to them – it’s so personal.

Creativity and recording

Broderick’s discography since those days is extensive – averaging one or more release a year. Still in his early 30s, he has seventeen albums on Spotify, plus several EPs and singles and many collaborations. His work ranges from the crafted Home album from 2009 to the meditative solo piano works on the Grunewald EP from 2016. His most recent work is a tribute to the experimental singer and cellist, Arthur Russell, and he is just about to embark on a German tour with Allred.

The creative process for Broderick, however, is unpredictable.

I’m not a super-organised person. I don’t do well with a strict schedule, especially with creativity. … when it comes to being creative, if I plan out a time to work and make music, and that time comes around, it often feels a bit contrived.

The inspiration comes in at times that really feel out of my control. My most productive work happens spontaneously and often in the most inopportune times, like when I’ve got a house-guest and I’ve got an idea and I need to go work on it, or it’s the middle of the night and I can’t stop thinking about this or that. With music it really just comes when it comes.

The solo piano work ‘It’s a Storm When I Sleep’ is an example, written while house-sitting for friends.

I had this whole house to myself and there was a piano there and I sat down and started going like this [he taps two fingers, one from each hand, on the table] just rhythmically playing a couple of keys back and forward, just getting into the wall of sound that that would make, and then I came up with a simple progression from that.

The work, which he has only recently transcribed and published, is eight minutes of perpetual motion, written completely in the bass clef.

It’s a really transportive thing to do on your own because the sound just fills the room and swirls around; it’s very hypnotic. There’s stamina needed for sure [when performing the work]. Stamina is the main thing. When I first started playing it my hands would ache.

The apparent simplicity in Broderick’s music, plus having released music on the Erased Tapes label, means his work is sometimes associated with ‘neo-classical’ composers, but he doesn’t identify with any particular sound. ‘Less is more’ was something Broderick gravitated to early on.

Sometimes I’ll hear the work of another composer and I’ll say what an interesting chord change. I wish I could come up with a chord change like that. I think anyone can get a little stuck in their own patterns, in their own ability, because while I do have some musical education I wasn’t that interested in learning. I just wanted to play. It seemed irrelevant to me and over the top.

I’m a firm believer in less is more and you certainly don’t need that stuff to make a good song. Some of my favourite songs are two or three chords. It really doesn’t have to go anywhere for me.

Human Eyeballs on Toast

Several of Broderick’s songs use spoken word, such as ‘These Walls of Mine’ I and II, and are quite direct; others address contemporary issues, such as animal cruelty (‘Human Eyeballs on Toast’); but other lyrics are ‘not necessarily about something exact. It’s more about a feeling or a series of feelings.’ His song ‘Sideline’ was written when he was staying with family out in the country and there was tension in the house.

The neighbours said I could borrow their van to drive into the city to meet some friends. … There was no stereo. Usually in a car I would put on some music, so I started to fill the sound by myself. I just started to sing and [‘Sideline’] was what came out. I was reflecting on how things were feeling at my father’s place at that time, and then intertwining that with other experiences and feelings I’d had over the recent years.

Being on the sideline is like perhaps being depressed. When you’re depressed it’s almost like you’re not engaging in your life. You’re sitting there watching yourself, wishing you’d get in the game.

With more recent songs, ’there’s no confusing what they’re about. I’m enjoying that now after many years of having written things a little more vaguely, but I still appreciate both.’

Broderick’s most well-known piece is ‘Eyes Closed and Travelling’, which has over 28 million plays on Spotify due to it being included in a ‘Peaceful Piano’ playlist. ‘That doesn’t mean a whole lot to me. At the same time it doesn’t mean nothing either,’ he says. He reflects often on the impact of the internet on music. At times, he feels concern at the sheer amount of music available online and feels the need to reduce his own output. However, he’s conscious of how the internet has changed his career.

If it weren’t for the internet I don’t even know if I would have a career through music. I met a band through MySpace. Spotify sends out one song of mine to millions of people. All these things help spread the music. Those people – maybe they won’t buy your record, but they might come to your show and they’ll talk to you and buy something from your little merchandise table. It all has its own way of going around.

Home in Ireland

It’s not clear whether or not Broderick and his family will stay in Ireland. He mentions the cost of housing as well as the lack of an easily accessible international airport in the west of Ireland as challenges that make it unlikely, but nonetheless, he suspects he can start to hear the influence of Irish music in his work.

I was just recently doing some mixing on a live concert of mine from several years ago. I was noticing the difference in how I sing. I’ve got these little ‘twirls’ in my stuff now and it’s a very Irish thing. I know some of it I picked up from my wife because she adorns her melodies. I’ve definitely picked some of that up and not consciously. It just seeped right in there.

For more on Peter Broderick, including upcoming concerts, visit www.peterbroderick.net.

Published on 31 January 2019

Toner Quinn is Editor of the Journal of Music. His new book, What Ireland Can Teach the World About Music, is available here. Toner will be giving a lecture exploring some of the ideas in the book on Saturday 11 May 2024 at 3pm at Farmleigh House in Dublin. For booking, visit https://bit.ly/3x2yCL8.