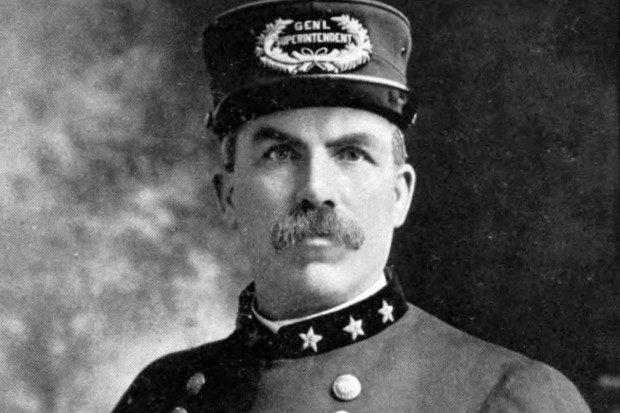

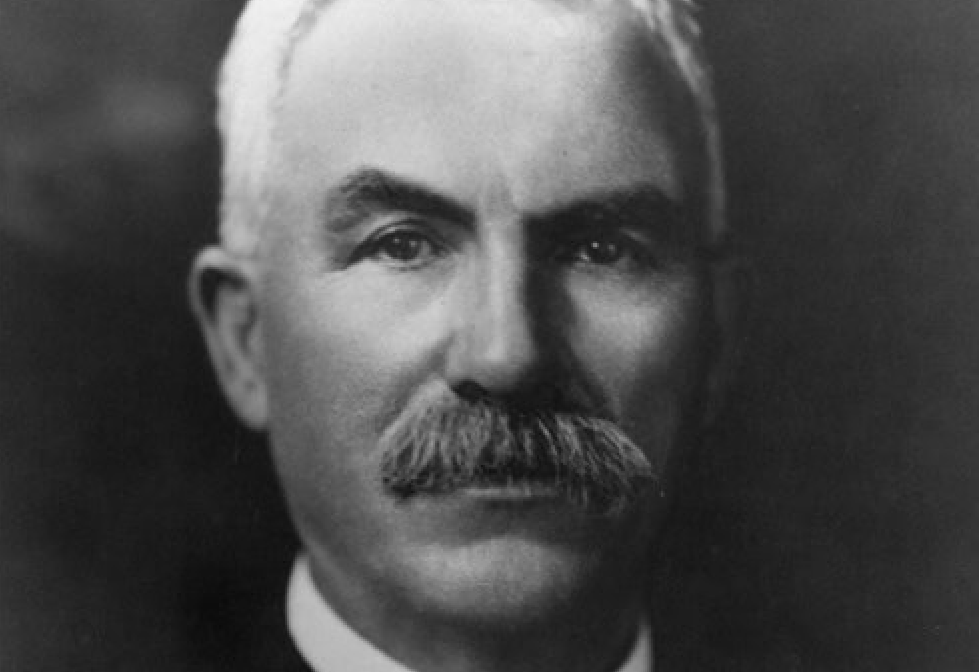

Francis O'Neill

'There are no good – even tolerable – musicians coming from Ireland anymore and we don’t expect them': Francis O'Neill Letters Published Online

Following the recent publication of his book The Cry of a People Gone: Irish Musicians in Chicago, 1920–2020, Chicago-based Irish music historian Richie Piggott has now published five previously unpublished letters written by the renowned collector Francis O’Neill.

The letters, written between 1906 and 1914, were sent to O’Neill’s friend and supporter, the fiddle player Patrick O’Leary, who was originally from County Cavan but emigrated to Adelaide, Australia, in 1876. The correspondence was given to Piggott by Judith O’Loughlin, great-granddaughter of O’Leary. Piggott has published the original letters with transcriptions on his website, www.richiepiggott.com.

Irish music in Ireland and Chicago

The letters provide a range of insights into Irish traditional music in Ireland and Chicago at the time, and illustrate O’Neill’s frustration with the lack of efforts being made to support the music and his concern about its decline, which drove his collecting work. Born in Tralibane, Co. Cork, in 1848, O’Neill emigrated to the United States in the 1860s, settling in Chicago in the 1870s. He collected music from Irish emigrants and many other sources, publishing his first volume of 1,850 tunes, O’Neill’s Music of Ireland, in 1903, when he was chief of police in the city. This was followed by The Dance Music of Ireland (1907), 400 tunes arranged for piano and violin (1915), Waifs and Strays of Gaelic Melody (1922), Irish Folk Music: A Fascinating Hobby (1910), and Irish Minstrels and Musicians (1913). The five letters document his perspective when he was deeply engaged in this publishing and collecting work.

A return to Ireland

The first letter from 1906, which is incomplete and undated, comes at a time when O’Neill had recently visited Ireland after an absence of 41 years. He writes to O’Leary: ‘I went to Ireland this summer to find the “old sod” improved in a material way’ but he observed that ‘There is not a first class Irish piper in Ireland today and only a few indifferent ones.’

O’Neill is clear about some of the main reasons for the decline: in the first instance, the negative influence of the Catholic clergy, and secondly, the general indifference in Ireland towards the music. He writes to O’Leary: ‘You know the many causes which discouraged pipers and fiddlers not the least of which were the priests. Now the utter indifference of the public is the principal cause.’ O’Neill adds that his inaugural volume ‘is selling steadily but slowly’ but that ‘the price seems to unnerve intending purchasers’. He notes that ‘About 250 copies have been sold in Ireland’.

The collector recognises the value of his work and is driven by altruism: ‘The old jigs and reels. [sic.] Can’t very well die out after this although the undertaking is unprofitable financially I regard it as practical patriotism’.

He also refers twice in the letter to the death of his son, Rogers, due to spinal meningitis in 1904 (O’Neill had ten children and several died young). By this time in 1906, O’Neill, aged 57, had retired as chief of police in Chicago and he says that ‘I am retired from active service as my own choice. I lost all ambition on the death of my son.’

‘A littleness of spirit’

The second letter, from 14 September 1908, is written after the publication of The Dance Music of Ireland the previous year. O’Neill’s frustration is clear and he feels a lack of support for his endeavours, particularly among Irish people at home and abroad: ‘A conviction has been reluctantly forced upon me, that a littleness of spirit which chills endeavor and a jealousy often malignant in its intensity has rendered practically abortive the efforts in almost every field which unselfish enthusiasts have entered – is a characteristic of our race.’

In the third letter, dated 14 June 1911, he makes further observations about music in Ireland and the States, writing that efforts to revive the Irish harp have been an ‘abject failure’, that ‘There are no good – even tolerable – musicians coming from Ireland anymore and we don’t expect them’, and that ‘Musically in this generation our position is pitiable.’ He also says that the Irish Music Club of Chicago is moribund because of in-fighting, and tells the story of a priest who asks Irish musicians in Chicago to play for a fundraiser in order to generate funds to restore a church back in Ireland – to O’Neill, this was the height of hypocrisy. He concludes on a despondent note: ‘I have an immense accumulation not yet printed but what’s the use. No one wants it. Nothing appeals to our Irish Americans but the very latest hit. In Ireland they seldom buy but they will travel great distances to borrow gift books.’

‘Doomed to be a failure’

The fourth letter from 17 October 1912 contains further observations on the decline of traditional music in Ireland. He mentions a piper named James Byrne of Mooncoin, Co. Kilkenny, but says that Byrne is now ‘the only union piper now in the South of Ireland excepting May McCarthy. Think of it – not a piper in Kerry Clare, Limerick or Tipperary and I don’t know how many more counties.’ He says that new immigrants to America are not even familiar with the pipes: ‘Many new arrivals look at an Irish pipe with curiosity having never seen or heard one at home.’ Again he is despondent about his publication work but also sees its value: ‘My forthcoming volume will be much longer than Irish Folk Music A Fascinating Hobby and ought be interesting. Yet it is doomed to be a failure financially as the Irish seldom buy any books though they sometimes borrow.’

The final letter in the collection, dated 12 May 1914, shows that O’Neill’s work was beginning to garner more support from certain quarters. He writes: ‘Praise galore from press and people has been mine, but our people are too much engrossed in other affairs to be actively interested in such work as I have been engaged in. The patronage has been disappointing, altho’ the Irish press and the leading Irish or Catholic papers gave the work praiseworthy recognition. Even the leading musical journals were unanimous in its praise.’

He ends on a more positive and satisfied note: ‘I feel I have done something while others have merely talked or deluded their hearers though my experience has cost me at least £1000/ to say nothing of my labor of years and years. Now I am a free man my ambition gratified and my plans fulfilled and finis written on my musical literary labors – Thank God.’

O’Neill would nonetheless go on to publish three more books and live until 1936. His publications have been hugely influential on Irish music and his achievements have been explored in publications such as Nicholas Carolan’s A Harvest Saved: Francis O’Neill and Irish Music in Chicago (1997), and Michael O’Malley’s 2022 book, The Beat Cop: Chicago’s Chief O’Neill and the Creation of Irish Music. To read the full Francis O’Neill letters, visit www.richiepiggott.com/o-neill-letters.html.

Subscribe to our newsletter.

Published on 18 January 2024

Toner Quinn is Editor of the Journal of Music. His new book, What Ireland Can Teach the World About Music, is available here. Toner will be giving a lecture exploring some of the ideas in the book on Saturday 11 May 2024 at 3pm at Farmleigh House in Dublin. For booking, visit https://bit.ly/3x2yCL8.