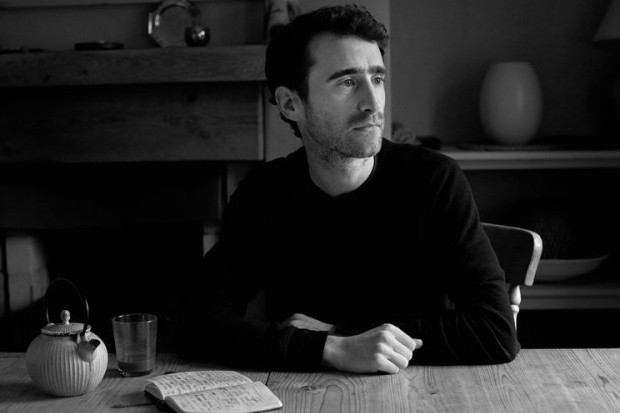

Neil Ó Lochlainn (double bass) and ensemble performing his new work 'Emain Ablach' at An Taibhdhearc in Galway. (Photo: Journal of Music)

Into Another World Where Jazz and Traditional Music Merge

Emain Ablach is the name of an otherworld in Irish mythology, home of the sidhe, possible birthplace of the god Lug, and associated with swans and apples. It’s also the title and setting of a new work for ensemble and narrator by Neil Ó Lochlainn, with words written by the Irish-language poet Aifric Mac Aodha. The work was performed at An Taibhdhearc, Galway, on Friday 17 November, and again at the Smock Alley Theatre in Dublin on the 18th.

I last heard Ó Lochlainn live at Solstice Arts Centre in Navan for his Tommie Potts-influenced Tairseach earlier this year, which he performed on bass and traditional flute with Sam Comerford on saxophone and clarinet and Ultan O’Brien on viola and fiddle. That suite was intimate and dreamlike, played by the trio to an audience seated almost arm’s-length away.

Emain Ablach – a merging of jazz and traditional music elements – is on a larger scale in just about every dimension. Featuring fourteen performers (the above trio joined by uilleann pipes, concertina, percussion, trombone, harp and trumpet) and narrator, and lasting about 75 minutes, it also feels more ambitious, grappling with mythology and conceptual space. It sets Mac Aodha’s three-part poem, read by Billy Mag Fhloinn, with the words seeming to give impetus to the musical narrative, and often coming as interjections or breaks in the musical momentum.

Unshakeable foundation

The work begins quietly, with Mag Fhloinn reciting the first couple of lines of the text and a bodhrán laid against the wall and played with jazz brush by Brendan Doherty (one of five performers on either tuned or untuned percussion; his work gave the performance an unshakeable foundation). Next came a broad chord for the whole ensemble, around which a lugubrious trumpet solo by Laura Jurd formed, before it settled into a jig played by concertina and pipes (Eoghan Ó Ceannabháin and Mark Redmond respectively) over a firm groove held on drum kit by Doherty and a duplet beat on the first beat of each bar meaning the music never quite settled.

This style of repetitive composition can be catnip for people who enjoy pattern recognition, allowing plenty of time to really tune into how the different parts interlock. Sometimes it’s easy to get so sidetracked focusing on these things that you fail to notice bigger changes until they’ve already happened, say as the music moves from a dance tune to lounge jazz.

There’s plenty of literality in the treatment of the text. Early in the work, the music reaches a raucous, driving passage as Mag Fhloinn recites – yelling into the microphone and even then hard to make out amongst the chaos – ‘Ard an nuall a éiríonn / ar gach taobh’ (David Wheatley’s poetic translation in the programme renders this as ‘The clamour raised high / on every side’). Later, in a section called ‘Caoineadh na hEala’ (‘The Swan’s Lament’), he intones the verse’s repeated ‘Uaigneach (‘Lonely’) with hollow weight. Under this, Colm O’Hara’s unsettling trombone solo is built on air noise and occasional fluttering notes that seem to appear and flee the light.

Mesmerising solo

Ó Lochlainn as a composer is generous and self-effacing, and to an extent Emain Ablach feels a little like a concerto for ensemble, with every performer (though least of all Ó Lochlainn himself) getting at least one prominent solo, and several sections of the work see the performers splintering into smaller groups playing different styles of music. At one point, the music found a place of stillness for a mesmerising vibraphone solo by Berlin-based Evi Filippou. At another, the whole ensemble seemed engaged in a riotous free jazz routine, but the fiddlers Lucia MacPartlin and Ultan O’Brien were playing together and watching each other very carefully, their material audible through the dense texture but only just – until the rest of the group broke away and they were revealed – somewhat inevitably – to be playing a reel.

I wouldn’t call this a typical trick of Ó Lochlainn necessarily, except in how comfortably he places these genres of jazz and traditional music against each other, and how natural he makes them feel in each others’ company. There’s a deep understanding of what makes his various musical influences tick, and it’s at that level that his music operates, so a section might not sound like Reichian contemporary music, but it knows from Reichian contemporary how to sit in place and just be; it might have the character of free jazz, but with the phrasal ebb and flow of a traditional dance tune.

Ó Lochlainn’s music has a unique blend of jazz, traditional and post-minimalist contemporary influences that coalesce into a voice that is distinct and self-assured. These aren’t necessarily natural bedfellows, but through them Ó Lochlainn creates with his collaborators a complex and unique sound. Indeed, his own instruments – what could be more disparate than traditional flute and upright bass? – are almost emblematic of his bridging these musical worlds. Tairseach and albums like Roscana and Umhaill have been convincing but have tended towards the insular and liminal. Emain Ablach is longer, more structurally complex and defined, and larger in scope and scale than its predecessors, and it shows Ó Lochlainn as a composer able to work at this level. It’s the same voice as those works, but the music looks out as well as in, seeing its way to different worlds, mythological and otherwise.

Visit www.neiloloclainnmusic.com.

Subscribe to our newsletter.

Published on 23 November 2023

Brendan Finan is a teacher and writer. Visit www.brendanfinan.net.