Inma Pavon and Quiet Music Ensemble (Photo: Tomasz Madajczak)

Listen to the Community

As event titles go, In Your Own Time and Place feels somewhat prosaic, if not folksy. But place is an important element of this three-day Cork celebration of musical improvisation, which took place on 14–16 September. In the broader geographic sense, Cork has a deep history of sonic experimentation and over the course of its three days, In Your Own Time and Place highlighted the standard bearers of the scene. But if the scene has to have a patron saint, it surely must be the late musician, composer and thinker Pauline Oliveros.

Daniel Weintraub’s documentary, Deep Listening – The Story of Pauline Oliveros, may be a surprisingly conventional portrait of the late American innovator, but as the opening event of the weekend it was a useful primer for the events to come.

It was also apropos. Oliveros had notable connections to Cork, having conducted the first Deep Listening workshop held in Ireland at the 2008 Quiet Music Festival, as well as purchasing an artist retreat on the Beara Peninsula with her wife and creative partner, Ione.

Clocking in at close to two hours, Deep Listening is certainly exhaustive, tracing Oliveros’ journey in sound from formative childhood listening experiences to her pioneering use of technology in the area of inclusivity. It’s an engrossing watch, enriched as it is with old footage – an archive of personal photographs, newspaper clippings, performance programmes and scores, as well as contributions from the likes of Terry Riley and Alvin Lucier.

Playing with the utmost quietness

In Your Own Time and Place featured a number of people who performed with Oliveros, one of whom is Quiet Music Ensemble bandleader and composer John Godfrey. After the screening, the Ensemble, comprising Yseult Cooper-Stockdale (cello), Nick Roth (saxophone), Ensemble regulars Dan Bodwell (double bass) and Roderick O’Keeffe (trombone), and Godfrey (guitar and electronics), performed music in Cork Opera House’s bar and lounge areas by Irish and international composers.

The first piece, Aioi: leaves laden with words, composed by Anna Murray, was inspired by Noh theatre. In that tradition the pine tree has enormous symbolism – it was through that tree that Noh was passed down from heaven and the back stages of Noh theatres were adorned with a painting of a pine tree. Murray’s graphic score uses the image from the oldest Noh theatre. Each musician had a variation of that image, which, in an intriguing twist, was covered with a similar sized sheet but with a window cut out in different places, meaning each one sees only a part of the overall image.

Playing with the utmost quietness, the band created what I can only describe as a gaseous sound. Sitting out of the overall sightline of the band thanks to the curvature of the room, I, too, felt like I wasn’t taking in the full tree. Was that sound like air being slowly left out of a balloon, bass strings being rubbed, or a trombone?

But no matter! Outside, on an inclement evening, one could also hear the relentless patter of rain and the low rumble and hiss of traffic along the adjacent quays. However, to decide that the group was battling the external conditions would be a misunderstanding. No doubt Oliveros would concur.

At a certain point, the London-based Noh chant specialist Laura Sampson moved glacially into position on the stage. By this time the music, a sustained note, had achieved an otherworldly sense of drama and suspense. Dressed in the regalia, Sampson’s commanding voice alternated between sprechgesang and operatic, conveying a sense of refuge in an uncertain world. Straining to be closer to the spectacle, two audience members tip-toed across the wooden floor with such great care, as if there were dire consequences. It felt as if the whole world was on a precipice.

The tone of the music changed, becoming gruff, sinister and foreboding. An action painting in sound. The spluttering trombone brought another shading, sounding whimsical and cartoonish. And as Sampson intoned a line about being in the heart of the forest it occurred to me that the world without had melted away.

Laura Sampson and Quiet Music Ensemble in Anna Murray’s ‘Aioi: leaves laden with words’ (Photo: Tomasz Madajczak)

The next piece also had a graphic score, but it was centred around the choreography of Cork-based dance artist Inma Pavon. This world premiere of her composition 24 Houses was inspired by the places she has lived in since moving to the city 28 years ago. The scores were laid out around her like a square and, as she danced her story, the musicians responded to both her and the score.

Tiny spare clicks soundtracked Pavon as she hopped and swerved, as if negotiating a cramped and confined space. Then again, it could be the movements of someone trying to traverse the throng of a house party. To a low shrill note, like a house alarm going off further down the street, Pavon spun, her arms straightening and bending on a different axis around her. The piece became more discordant as it reached a climax of sorts, before trailing off after a series of rolling sax notes into the imperceptible distance.

The performance of Greek composer and sound artist Marianthi Alexandri-Papalexandri’s Resonators found the musicians stationed at narrow plinths spread out around the performance area and at the edges of the audience. These are the resonators. On each one sat a rotating platter on a motor board with contact mics attached. Objects attached generate sounds on rotation. Upon activation they hummed and vibrated like fans. Gradually, hollow clinky sounds began to be sprinkled throughout. With the lights completely dimmed, a particular atmosphere imposed itself on the room. Peering out through the rain-dimpled panes, we could have been in a submarine. The effect of the piece was mesmeric.

Changing the way they think

It became abundantly clear why Godfrey described the final piece, FOUND by Chance, by local artist Irene Murphy, as something so challenging to the Ensemble’s practices it changed the way they think about what they do.

Murphy read a text describing it as ‘an embodied composition’ that speaks of a primordial way of experiencing the world, a pre-linguistic state. While she read, the musicians commenced their performance. This involved them reaching out and exploring the space around them, sometimes touching each other, before turning their attention to their instruments. These were examined and scrutinised as if they were encountering them for the first time. Holding his bass by the headstock, Bodwell pushed and pulled it back and forth on its lower bout. Godfrey appeared to be testing the weight of his guitar. Holding it out by the neck and letting it drop on its strap button. O’Keeffe disassembled his instrument. In the dim light, observing their silhouettes against the glass, I was reminded of the simians at the beginning of 2001: A Space Odyssey. By Murphy’s reckoning, we must be witnessing their state before the arrival of the monolith. What possibilities would materialise should O’Keeffe throw his trombone in the air!

Was this music? It was certainly a musical performance. I found it quite astonishing, and I left the venue slightly dazed, feeling as if I had fallen up a staircase.

Irene Murphy (Photo © 2023 Robin Parmar)

Magical moments

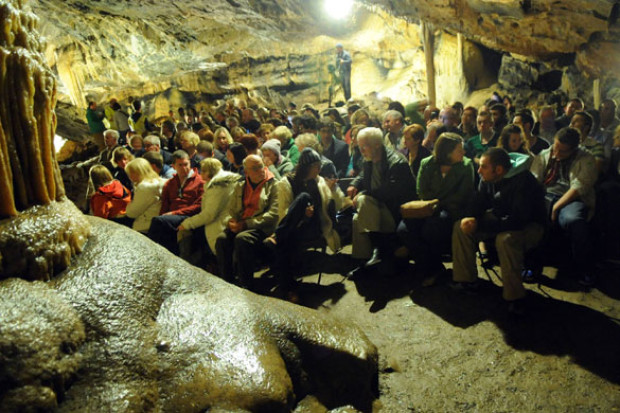

The centrepiece of the festival is the Sonic Vigil. Since it first occurred in 2005, a mammoth 12-hour session that took place in St Fin Barre’s Cathedral, the vigil has occurred in places of worship of different denominations, both consecrated and deconsecrated. Over the course of the last ten editions the way the vigil has been conducted has changed, but this event, inside the frontal area of the Cork Opera House, is the first to take place in a non-church venue. Is it more about the sound than the space? As Oliveros reminded us in Deep Listening, ‘music is a form of prayer.’

A computer programme ensured that each of the two dozen or so performers received a unique randomly generated schedule. Participants were only aware of the times in which they would play, which meant no one knew who, or indeed if anyone, would be playing at the same time. While not quite the feat of endurance that was the first Sonic Vigil, the six-hour span offered ample scope for magical moments of chance; such as seeing writer and musician David Toop wander by, scraping the edge of what looked like a large leaf with a little bow, as I entered the foyer.

On the top floor, perched in the corner, on a high stool on a stage, composer Andy Ingamells quietly played cello. Across from him local sound artist Harry Moore, paying close attention, was also bowing some objects. Next to him, Anne Marie Deacy appeared to do something briefly at one of her devices. Or did she? It was hard to tell as some other unidentifiable sound crept into the space that could have emerged from anywhere. At the opposite end of the room, Claudia Barton stood up on the couch and, leaning into the void, began scraping a few notes from a handmade instrument – a steel pipe welded to a brass cone. It all seemed wonderfully anarchic and utterly spontaneous. And in a way it was, even if there was an artificial intelligence that shaped their ends.

Anne Marie Deacy at Sonic Vigil (Photo © 2023 Robin Parmar)

On the floor below, Danny McCarthy carefully etched notes from a guitar with all the concentration of an engraver. Karen Power was generating a clicking sound, perhaps sourced from one of her field recordings of arctic ice. On the floor, Irene Murphy arranged clinking rectangular sticks of stone as if it were a puzzle. Katie O’Looney rubbed a clam shell against her kora. From up above, Cathal Roche played clarinet down to the floors below.

Belgian composer and sound installation artist Pierre Berthet paraded a variety of improvised instruments. At one point he promenaded holding an open umbrella with fastened branches whose clusters of dried berries pitter-pattered like rain due to the vibrations caused by an attached motor.

Another remark of Oliveros resonated: ‘I never tried to build a career, I only tried to build a community.’ Here, indeed, was a vibrant manifestation of community, crystallised in the presence of Farpoint Recordings’ Anthony Kelly and David Stalling. Artists in their own right, their label has long been connected with Sonic Vigil, having documented a few of its editions and supported work by many of the artists present on the day; as well as absent friends – a candle burned in memory of the recently deceased American artist Steve Roden.

In the foyer, Tony Langlois teased wispy traces of melody from his electric guitar. On the first floor, installation artist Rie Nakajima tilted ball bearings around a biscuit tin lid. As Toop rustled wood shavings in a parchment paper, John Godfrey wrung ethereal notes from his guitar. It felt rather solemn. That is until Sean Taylor’s fragmentary spoken text of found phrases overheard in Limerick city intruded upon the scene. ‘Is this a joke?’ his disembodied voice could be heard to declaim from the lobby. It was like Christmas Eve revellers landing in at midnight mass after closing up time in the pubs. ‘It was, without doubt, the most beautiful rosary I have ever heard,’ he continued. Ah, now it really has been the most beautiful vigil.

Subscribe to our newsletter.

Published on 14 December 2023

Don O'Mahony is a freelance arts journalist based in Cork.