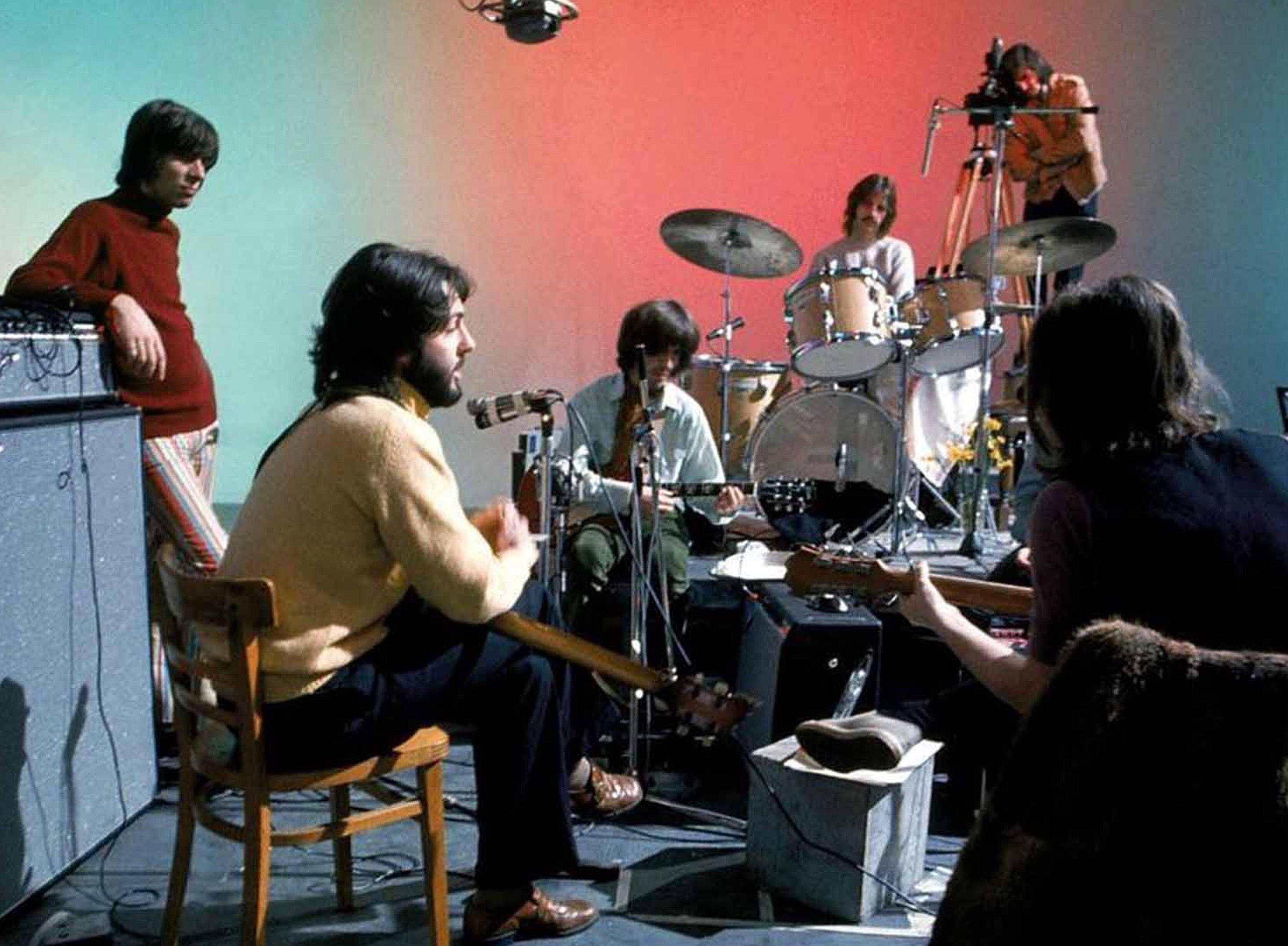

The Beatles in 'Get Back'.

What If We Had More Music Hubs?

In Peter Jackson’s new three-part Beatles documentary Get Back, we see the magical chemistry that arises when a group of musicians return day after day to the same space.

The Beatles are in a large room in Twickenham television studios in 1969 for almost two weeks, followed by a similar stretch in a still-being-built studio in Savile Row. They are working towards the album Let It Be, a documentary and a live show. Their instruments are there every day when they walk in, other creative people come and go, and the mood is one of collaboration, writing, composing and recording, conversations, experimenting, and working towards a goal. Every now and then, they jam old songs to keep the creative energy up.

In the first episode, Paul McCartney has no lyrics or structure for the song ‘Get Back’, but, in an almost supernatural moment, he starts to develop the chords and hum fragments of the melody, and gradually the group piece the new song together. The documentary flies against the idea of the solitary artist. The Beatles turn up with speculative riffs and scraps of lyrics and persist with them collectively until something starts to emerge.

Although we may be watching some of the greatest songwriters at work, and leaving aside the incredible footage, what we are also witnessing is something quite straightforward and universal: the creative process. It is basically the same for every group of musicians. They start with something tentative, play with ideas, then develop them, struggle with them, become frustrated and disheartened, discard elements and come up with others, and then, sensing a breakthrough, a flow appears, the energy levels go up and everyone locks in. The group gradually arrive at something they are happy with. And then the whole process starts over again.

What is interesting also is that if you watch Get Back you will realise how important the physical spaces are. They frequently discuss the acoustics and alter the set-up of rooms in order to help them work creatively. They have to commit to the room to build a dynamic. They know that part of the creative process is about being in the one place for long enough and getting a run at things. Musicians respond to working in a ‘hub’-type environment because it encourages them. The Savile Row studio even provides the space for the iconic rooftop concert on 30 January 1969, the culmination of their work. The value of Get Back is that it illustrates in prolonged detail how all of this develops, the centrality of creativity, and its relationship to the space around it.

So much has been written about the Beatles, and we constantly talk to and about musicians in the media, yet the creative process at the heart of a musician’s work, and the spaces that encourage it, are still relatively invisible to our society. How can this be? Perhaps it is because it is out of sight in bedrooms, practice rooms, studios, house garages and rehearsal rooms. We see the final product. Few can imagine the messiness of music, when artists don’t have answers to all the creative challenges they face, when the music is just fragments and ideas, but it is an essential part of what musicians do.

It is becoming clear, however, that this blindspot in society puts the music community at a disadvantage. We overlook the subtle creative spaces we have. Look at how hard the music community had to work to save the Cobblestone traditional music pub in Dublin. For thirty years it has been at the heart of transmission of this music in the capital, but it is still so vulnerable. It is the same for other types of music. Everywhere today, when musicians are working on a project, they struggle to find places to practice and collaborate.

Music has specific needs – it has volume, and yet also needs quiet, and needs to be in a place where musicians can work without disturbing others, or avoid being disturbed or asked to stop. So many ‘artist spaces’ that are created as part of town and city developments are unsuitable. They are imagined for painters and writers, but you can’t put a musician, or a group of musicians, next to them, never mind beside a group of houses, apartments or businesses. Musicians also require equipment, from instruments to cases to amplification, and they need a space where they can store it. Plus they need recording equipment to document their processes. In Get Back, the Beatles are frustrated that the record company won’t provide an eight-track recording system for their demos, so George Harrison brings his own from his house. It arrives in a truck and is wheeled in.

We have a decades-long housing crisis, caused by an economic orthodoxy that marketises everything, and we are well past the point where we can rely on cultural spaces to organically appear. Where we don’t have ‘music hubs’ we need to develop them, places where musicians can rehearse, collaborate, record, store instruments, write, compose, network, and focus on all the other aspects that are involved in creating music and building a career. If they don’t have such spaces, they will always be under pressure and never get a proper creative run at the work they need to do – and which we get to enjoy. We saw in Get Back what happens when artists do get that space. Not everyone can be the Beatles, but that’s not the point: the basic equation of the creative process – space + collaboration = art – is the same.

What is frustrating about the lack of emphasis on music hubs in society is that ‘innovation hubs’ are thriving because the business community managed to put forward the very same argument for the need for creative spaces. They know that the key to growing successful enterprises is having a space for collaboration, creativity and the exchange of ideas, and so governments have backed them unreservedly. There are now over 400 innovation hubs in Ireland! There is even a national summit for them next week. Where is the equivalent support for music hubs?

It is time we realised their importance. Our cities, towns and villages are reimagining themselves in the wake of the pandemic. The commute is dead. People want energy, life and creativity in their communities – and that’s what musicians and music hubs bring.

Published on 2 December 2021

Toner Quinn is Editor of the Journal of Music. His new book, What Ireland Can Teach the World About Music, is available here. Toner will be giving a lecture exploring some of the ideas in the book on Saturday 11 May 2024 at 3pm at Farmleigh House in Dublin. For booking, visit https://bit.ly/3x2yCL8.